State Pension Funding Levels Stayed Stable Despite Volatility

Updates to Pew’s fiscal sustainability matrix through 2023 show more states meeting contribution goals

The reported funding gap for state pension plans—the disparity between promised benefits and available assets—was $1.32 trillion in 2023, according to 50-state data collected by The Pew Charitable Trusts. This represents a $44.7 billion increase over 2022, driven primarily by increases to liabilities from benefit changes and differences between what plans assumed for salaries, longevity, and similar workforce and demographic trends and what actually happened.

However, even amid volatile markets, state funds showed signs of resilience. The overall funded ratio—the share of pension liabilities matched by plan assets—was 74% in 2023. That matched 2022, meaning that state funds had about the same level of dollars available to meet long-term obligations.

That ratio stayed steady even though the number of states that met a key contribution target—the net amortization benchmark, which measures whether employers’ payments are sufficient to prevent pension plan debt from growing—dropped from 49 in 2022 to 41 in 2023. Collectively, however, states met the net amortization benchmark and paid down $36.3 billion in pension debt in 2023. Additionally, for the fifth year in a row, all 50 states managed to sustain an operating cash-flow-to-assets ratio above -5%, the threshold that Pew has identified as an early warning sign of potential insolvency.

Funded ratio

The overall funded ratio remained unchanged in large part because plans’ investment performance improved. According to data from Wilshire TUCS, the global financial services firm, the median plan saw a significant increase from a -7.77% return in 2022 to 8.32% in 2023. As the typical pension plan expects to generate average returns of around 7% annually, this level is on target for most. In total, state pension plans returned $229.7 billion in net investment income in 2023.

Thirty-five states reported an improved funded ratio from the prior year. South Dakota, Tennessee, and Washington remain at or above 100% funded. On the other hand, New York, which had been fully funded in 2022, fell to 90% funded in 2023.

The improvement trends are most important when viewed in the long term, as states that make consistent contributions can compensate for prior shortfalls. For example, officials in West Virginia have committed to improving pension funding. In 2003, the state reported a 40% funded ratio, the lowest in the country. But thanks to funding policies designed to pay down debt, the funding gap has been steadily shrinking. In 2023, West Virginia had an 89.7% funded ratio representing a $2.2 billion funding gap, a vast improvement from 20 years earlier.

Net amortization

Although investment returns drive short-term ups and downs in pension funding, long-term sustainability comes from consistently making adequate contributions to stabilize plan funding and pay down pension debt. The net amortization benchmark provides a metric for evaluating how states are faring in that effort; states that meet or exceed this measure can expect to see their funding gaps stabilize or shrink over time.

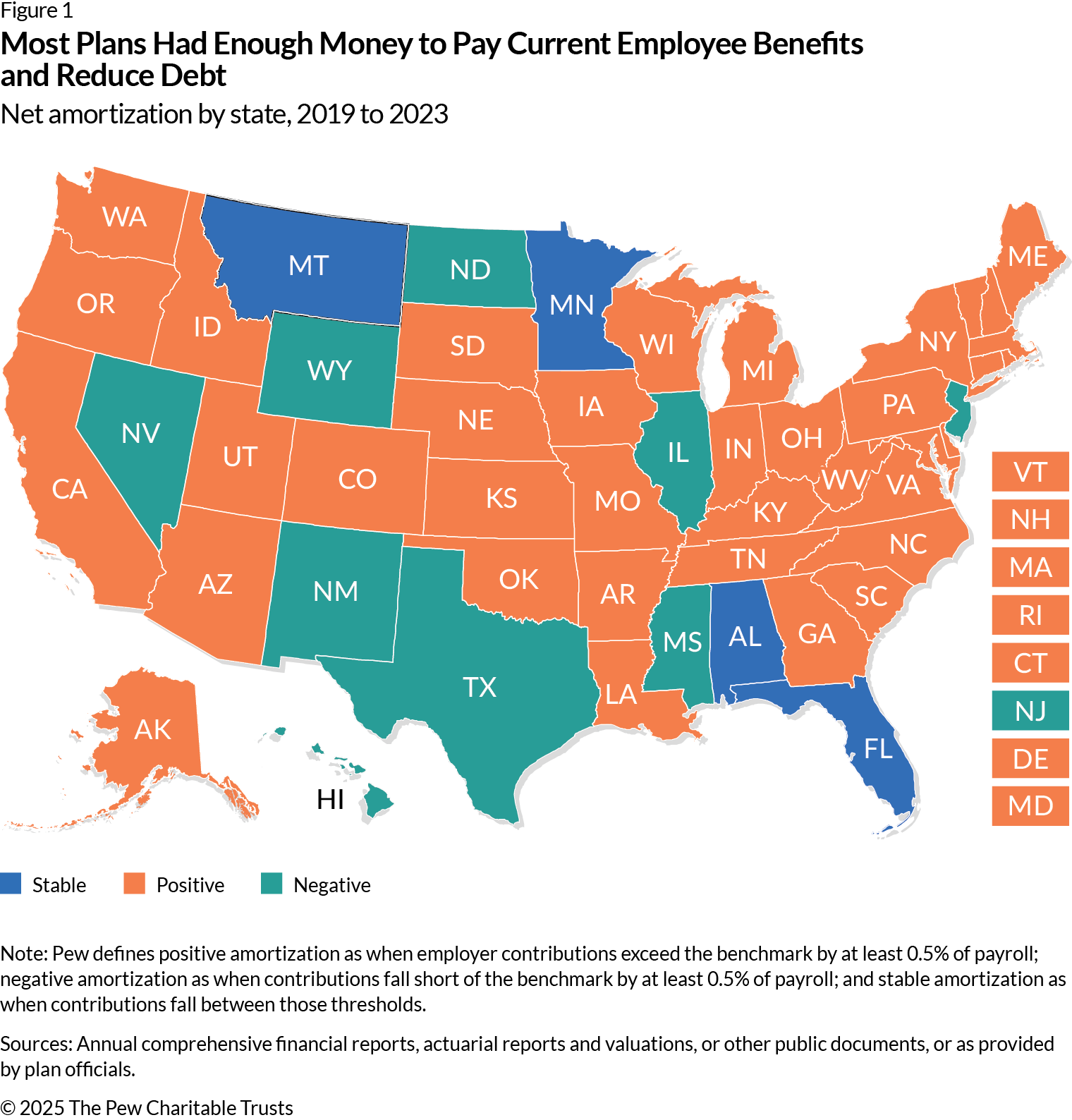

However, because the net amortization benchmark is subject to investment volatility, assessing contribution adequacy over time can help to clarify plan sustainability. From 2019 through 2023, 37 states had an average positive amortization, meaning they made contributions that were large enough to pay down pension debt. Four had stable amortization, with payments that were adequate to prevent debt from growing. And nine states’ contributions did not cover benefits and interest over the five-year period, resulting in negative amortization and growing pension debt.

Historic contribution volatility

To determine how pension costs might affect state budgets, Pew measures historic contribution volatility, which is the gap between the highest and lowest employer contribution rate since 2007, just before the Great Recession, which started late that year. A smaller range indicates more stable employer costs, which benefits states by improving predictability in budgeting and in debt levels. A larger range means that state budgets have had to deal with significant volatility in the share of public resources allocated to pensions.

From 2007 through 2023, five states—Arkansas, Idaho, Nebraska, South Dakota and Wisconsin—maintained their contribution volatility within 3% of payroll while maintaining well-funded pension plans. Meanwhile, Kentucky, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania had high levels of contribution volatility as policymakers struggled to address past shortfalls and policy mistakes, requiring increases in pension contributions.

In 2023, contribution volatility rates ranged from 1% to 46% as states continued to see an increase in contribution volatility from 2022: Seventeen had an increase over the prior year. This marked rise in contribution volatility could make it challenging for these states to plan for the future.

For some states, high volatility may not be a warning sign of fiscal distress. In recent years, some have opted to raise and lower contribution rates deliberately, increasing payments when economic circumstances were good and decreasing them in economic downturns.

For example, Connecticut’s fiscal guardrail policies allocate revenue surpluses toward boosting the state’s budget reserve fund and paying down pension debt. From 2017 to 2023, the state made an estimated $3.3 billion in pension contributions above the actuarial schedule, the bulk of that—$2.6 billion—in 2023.

Similarly, Colorado policymakers required increased pension contributions in the more prosperous years of 2018 and 2019. That helped them reduce contribution rates in the pandemic-related turmoil of 2020 without falling below the state’s target funding policy. The state then scheduled a makeup payment in 2022. From 2018 through 2023, Colorado’s pension contribution rate ranged from a low of 18% of payroll to a high of 26% of payroll. That represents a significant amount of volatility, but policymakers could dictate the timing and scale of the changes.

Such relatively new approaches to contribution volatility highlight how states can use all of the fiscal levers at their disposal, practices worth watching going forward.

Fiscal sustainability matrix 2023

To help policymakers navigate the inherent uncertainty of pension management and assess the resiliency of their plans, Pew created a 50-state matrix of fiscal sustainability. This tool collects critical information into a single table to highlight the practices of successful states and facilitate comparative analyses, using three sets of metrics:

- Historical actuarial metrics are the foundation of any fiscal assessment and show how past policies contributed to plans’ current financial position. But they provide little information with which to assess future investment or contribution risks.

- Current financial metrics, based on historical cash flows and funding patterns, provide the information necessary to assess whether a plan is adhering to funding policies that target debt reduction or is at risk of fiscal distress, such as underfunding or insolvency.

- Budgetary risk metrics provide essential information to help policymakers plan for uncertainty or for volatile costs and to prompt reforms when needed to ensure that pension plan costs and risks, which are largely borne by state and local budgets, do not crowd out other important public investments.

Fiscal Stability Dashboard

| Actuarial Metrics | Plan Financial Metrics | Budget Risk Indicators | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Funded Ratio, 2023 | Change in Funded Ratio, 2008-2023 | Employer Cost/Payroll | Operating Cash Flow Ratio, 2023 | Change in OCF | Operating Cash Flow Ratio, 2014 | Net Amortization, 2023 | Historic Contribution Volatility | Assumed Rate of Return | Normal Cost Sensitivity |

| Alabama | 63.1% | -14.0% | 12.7% | -4.13% | 0.0% | -4.1% | Negative | 7% | 7.4% | High |

| Alaska | 71.7% | -4.0% | 54.9% | -4.99% | -2.3% | -2.7% | Positive | 45% | 7.3% | Low |

| Arizona | 73.1% | -6.8% | 21.2% | -0.73% | 1.9% | -2.6% | Positive | 31% | 7.1% | Mid |

| Arkansas | 79.3% | -7.9% | 15.6% | -3.36% | -0.6% | -2.8% | Stable | 2% | 7.2% | High |

| California | 76.4% | -10.3% | 33.2% | -0.41% | 2.3% | -2.7% | Positive | 23% | 7.1% | High |

| Colorado | 67.6% | -2.2% | 20.8% | -3.19% | 1.3% | -4.5% | Positive | 16% | 7.3% | Mid |

| Connecticut | 54.4% | -7.2% | 62.6% | 3.26% | 6.0% | -2.7% | Positive | 46% | 6.9% | Mid |

| Delaware | 86.5% | -11.9% | 20.0% | -1.97% | 0.9% | -2.9% | Positive | 13% | 7.0% | High |

| Florida | 77.0% | -24.3% | 6.7% | -3.94% | 0.5% | -4.4% | Positive | 4% | 6.0% | High |

| Georgia | 75.9% | -15.7% | 22.3% | -2.79% | 1.1% | -3.9% | Positive | 12% | 6.9% | Mid |

| Hawaii | 62.1% | -6.6% | 28.4% | -1.16% | 1.0% | -2.2% | Positive | 21% | 7.0% | High |

| Idaho | 84.9% | -8.3% | 12.1% | -2.15% | -0.4% | -1.8% | Stable | 1% | 6.4% | Mid |

| Illinois | 43.3% | -11.0% | 53.3% | -1.52% | 0.0% | -1.5% | Negative | 45% | 6.8% | High |

| Indiana | 78.1% | 5.6% | 44.5% | 7.43% | 7.1% | 0.3% | Positive | 32% | 6.3% | Mid |

| Iowa | 89.8% | 1.1% | 9.6% | -2.82% | 0.1% | -2.9% | Positive | 4% | 7.0% | Mid |

| Kansas | 70.7% | 11.9% | 19.5% | -1.51% | 1.3% | -2.8% | Positive | 21% | 7.0% | Low |

| Kentucky | 49.1% | -14.8% | 43.0% | -2.27% | 4.7% | -7.0% | Positive | 46% | 6.3% | Low |

| Louisiana | 72.4% | 2.8% | 36.4% | -2.20% | 1.1% | -3.3% | Positive | 17% | 7.2% | High |

| Maine | 87.4% | 7.7% | 17.6% | -2.38% | 0.5% | -2.9% | Positive | 8% | 6.5% | Mid |

| Maryland | 73.3% | -5.1% | 17.1% | -2.14% | -0.3% | -1.8% | Positive | 10% | 6.7% | Mid |

| Massachusetts | 63.9% | 0.9% | 26.3% | -1.05% | 2.3% | -3.3% | Positive | 19% | 7.0% | High |

| Michigan | 67.0% | -16.7% | 40.5% | -1.46% | 4.3% | -5.8% | Positive | 32% | 6.0% | Low |

| Minnesota | 83.0% | 1.6% | 9.3% | -3.39% | 0.7% | -4.1% | Negative | 3.0% | 6.5% | High |

| Mississippi | 55.8% | -17.0% | 18.6% | -4.56% | -1.3% | -3.3% | Negative | 8% | 7.6% | High |

| Missouri | 78.0% | -4.9% | 22.0% | -2.73% | 0.2% | -2.9% | Positive | 10% | 7.1% | High |

| Montana | 73.9% | -9.5% | 15.2% | -3.54% | -1.8% | -1.7% | Positive | 6% | 7.2% | High |

| Nebraska | 97.3% | 5.8% | 10.3% | -2.16% | -1.2% | -1.0% | Positive | 2% | 7.2% | Mid |

| Nevada | 76.2% | 0.0% | 15.2% | -2.16% | -1.2% | -1.0% | Negative | 12% | 7.3% | Mid |

| New Hampshire | 67.2% | -7.9% | 20.8% | -0.90% | 0.7% | -1.6% | Positive | 13% | 6.7% | High |

| New Jersey | 47.1% | -25.5% | 33.6% | -1.16% | 5.7% | -6.9% | Positive | 29% | 7.0% | High |

| New Mexico | 66.2% | -16.6% | 18.1% | -3.08% | -0.1% | -3.0% | Negative | 6% | 7.1% | Mid |

| New York | 90.3% | -17.1% | 12.9% | -3.92% | -1.5% | -2.4% | Positive | 13% | 5.9% | Mid |

| North Carolina | 82.9% | -16.4% | 16.0% | -1.71% | 1.3% | -3.0% | Positive | 13% | 6.5% | Mid |

| North Dakota | 67.6% | -19.4% | 10.0% | -2.16% | -1.3% | -0.9% | Negative | 5% | 5.8% | Mid |

| Ohio | 79.6% | 2.3% | 13.8% | -4.30% | 0.6% | -4.9% | Positive | 4% | 6.9% | High |

| Oklahoma | 79.9% | 19.2% | 21.1% | -2.42% | -0.6% | -1.8% | Positive | 5% | 7.0% | Mid |

| Oregon | 81.7% | 1.5% | 16.6% | -3.80% | 1.2% | -5.0% | Positive | 26% | 6.9% | Mid |

| Pennsylvania | 63.0% | -24.0% | 33.6% | -2.42% | 3.6% | -6.0% | Positive | 34% | 7.0% | Low |

| Rhode Island | 64.7% | 3.4% | 27.1% | -3.05% | 3.4% | -6.5% | Positive | 11% | 7.0% | Low |

| South Carolina | 59.8% | -10.3% | 21.8% | -0.54% | 3.4% | -3.9% | Positive | 12% | 7.0% | High |

| South Dakota | 100.1% | 2.7% | 6.2% | -3.06% | -0.5% | -2.6% | Positive | 1% | 6.5% | Low |

| Tennessee | 100.6% | 5.5% | 13.2% | -2.16% | 0.0% | -2.2% | Positive | 3.2% | 7.0% | Low |

| Texas | 72.7% | -18.0% | 9.9% | -2.24% | 1.4% | -3.6% | Negative | 4% | 7.0% | Mid |

| Utah | 94.4% | 7.8% | 23.5% | -1.46% | -0.3% | -1.2% | Positive | 9% | 6.9% | Low |

| Vermont | 63.7% | -24.2% | 20.4% | -0.46% | 0.9% | -1.4% | Positive | 29% | 7.0% | High |

| Virginia | 84.5% | 1.0% | 15.4% | -1.85% | 0.4% | -2.3% | Positive | 12% | 6.8% | Mid |

| Washington | 104.6% | 4.3% | 6.3% | -1.37% | 0.6% | -2.0% | Positive | 6% | 7.0% | High |

| West Virginia | 89.7% | 26.2% | 18.4% | -3.65% | -1.9% | -1.8% | Positive | 7% | 7.3% | High |

| Wisconsin | 98.8% | -0.8% | 7.6% | -4.01% | -1.1% | -2.9% | Stable | 2.7% | 6.8% | Low |

| Wyoming | 81.4% | 2.1% | 11.1% | -3.66% | -1.2% | -2.5% | Negative | 10% | 6.7% | High |

Notes: Pew's measure of contribution adequacy tests whether employer and employee contributions are sufficient to keep pension debt Stable or to make progress in paying down unfunded liabilities through Positive amortization. States falling short of that minimum threshold have Negative amortization. Historic contribution volatility measures that gap between the highest employer contribution rate and the lowest over the period from 2008 through 2023. Higher values indicate employer costs have been less stable over that period. Normal cost sensitivity offers a measure of how uncertain the cost of benefits earned by newly hired workers is expected to be, based on the level of benefit, the assumed rate of return, and the presence or absence of tools to manage and mitigate risk in the plan design. This is a relative measure based on practices across the 50 states.

Sources: Annual comprehensive financial reports, actuarial reports and valuations, or other public documents, or as provided by plan officials.

Keith Sliwa is a principal associate, Ora Halpern is a senior associate, and David Draine is a principal officer with The Pew Charitable Trusts’ state fiscal policy project.