The Share of State Budgets Spent on Medicaid Posts Largest Annual Increase in 20 Years

In fiscal year 2023, the combination of expiring federal COVID-19 pandemic aid, slowing tax revenue growth, and rising costs for Medicaid led to an increase in the share of state revenue dedicated to Medicaid of 17.8%, or $44.4 billion, over the previous year—the largest single-year rise in at least two decades. States spent 15.1% of every state-generated dollar on Medicaid, up 2.2 percentage points from the previous year, though still about half a cent less than the 15-year average.

Individually, 17 states dedicated a larger share of their own dollars to Medicaid than they had, on average, over the previous 15 years—a sharp shift from fiscal 2022, when only Alaska exceeded its long-term average. Among these states, the differences varied widely, from 3.3 percentage points in Colorado to 0.03 percentage points in Georgia.

Looking ahead, the share of state budgets spent on Medicaid is likely to remain elevated through fiscal 2024, but potential shifts in federal policy could reshape the program’s fiscal footprint within states over the longer term.

States and the federal government share costs for Medicaid, which provides medical coverage for eligible children, adults, people with disabilities, and older Americans. Medicaid is most states’ biggest expense after K-12 education.

The Pew Charitable Trusts’ state Medicaid spending indicator excludes federal support, examining only the cost to states because this spending exerts pressure on state operating budgets, which rely on state-generated revenue.

Medicaid’s claim on each revenue dollar affects the share of state resources that is available for other priorities, such as education, transportation, and public safety. Federal law requires states to provide certain benefits for all eligible Medicaid enrollees, even during times of sluggish revenue growth. So policymakers have less control over growth in Medicaid costs than they do with many other programs.

In fiscal 2023, only five states saw the share of their own funds dedicated to Medicaid decrease compared with the previous year, but individual state increases ranged widely. Colorado saw the largest jump, rising 5.1 percentage points to 19.6% in fiscal 2024, while Delaware had the smallest increase, up just 0.004 percentage points to 10.8%.

State highlights

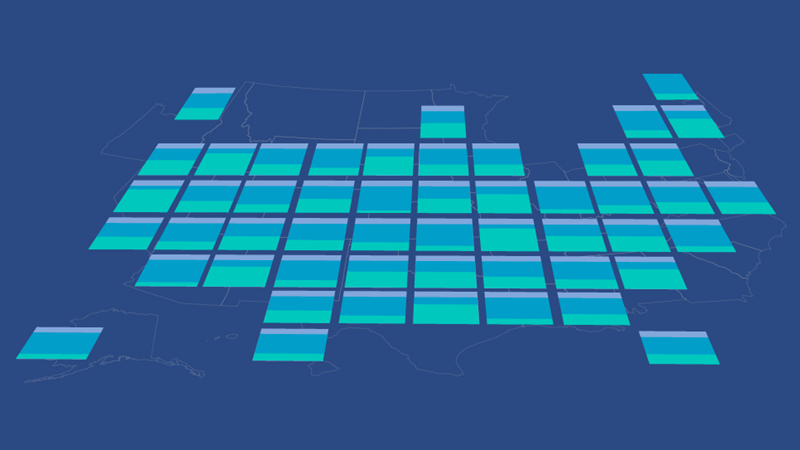

A comparison of the share of each state’s own-source revenue spent on Medicaid in fiscal 2023 with the previous year and with the average over the previous 15 years shows that:

- Alaska, Hawaii, New Mexico, South Dakota, and Wyoming were the only states where Medicaid spending decreased as a share of state-generated revenue from fiscal 2022 to fiscal 2023, and in all cases, the declines were less than 1 percentage point. The steepest increases were in Colorado (5.1 percentage points), New York (4.2 percentage points), and California (4.1 percentage points).

- 17 states spent a greater share of their own dollars on Medicaid than they had, on average, over the previous 15 years. Colorado was furthest above its long-term trend at 3.3 percentage points, as state Medicaid spending outpaced growth in own-source revenue. Maryland and Pennsylvania were next highest at 1.9 percentage points and 1.6 percentage points, respectively.

- Two states spent more than one-fifth of their own revenue on Medicaid in fiscal 2023. New York spent the largest share of any state at 23.5%, followed by Pennsylvania (22.7%) and Colorado (19.6%).

- The states that spent the smallest share of their own dollars on Medicaid in fiscal 2023 were Utah (5.5%), New Mexico (5.7%), and Hawaii (6.2%).

Trend drivers

In fiscal 2023, states collectively allocated $294.1 billion of their own resources to support benefits for 98.2 million Medicaid recipients—up 17.8%, or $44.4 billion, from the previous year. And this sharp rise in Medicaid spending came as growth in states’ own-source revenue slowed dramatically. Own-source revenue rose less than 1% from fiscal 2022 to fiscal 2023, compared with an increase of 14% from fiscal 2021 to fiscal 2022.

Several factors drove the rise in state Medicaid spending. First, enhanced federal Medicaid funding provided during the pandemic began phasing out in March 2023 and had fully expired at the end of that year, shifting more of the costs back to states. Second, more than 25 million people were unenrolled from Medicaid from Medicaid between the end of March 2023 and May 2024, but enrollment was still roughly 85.8 million people, 33.3% above pre-pandemic levels, at the end of fiscal 2023. States’ relative enrollment levels varied widely from more than 50% above pre-pandemic levels in Oklahoma, Missouri, Nebraska, and Wyoming to less than 15% above in New Hampshire and South Dakota.

Additional pressures on state Medicaid spending came from growing prescription drug costs, such as those from GLP-1-based weight loss medicines, increases in health care provider payment rates intended to help address workforce shortages, and higher service utilization rates because of the pandemic and because the nation’s aging population is increasingly reliant on long-term care. States are also beginning to see the budget effects of recently expanded coverage for children and for postpartum care. Reflecting these combined pressures, total federal and state Medicaid spending per enrollee reached a 50-year high of $9,109 in fiscal 2023, according to the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission.

Simultaneously, after surging in fiscal 2021 and fiscal 2022, tax collections—states’ largest source of revenue—started to decline in fiscal 2023, reducing the resources available to cover growing Medicaid costs.

Medicaid spending by level of government

Medicaid is state administered, but the federal government covered 59.9% to 81.4% of states’ bills for the program in federal fiscal 2023, bringing the federal share of total Medicaid costs to 67.4%. Federal spending on Medicaid grew by 4.9% that year, from $578.2 billion to $606.8 billion, a moderate slowdown after double-digit annual increases from fiscal 2020 through fiscal 2022 that were driven by temporary enhanced federal aid in response to the pandemic.

The federal government covered the highest portion of state Medicaid costs in Mississippi (81.4%), followed by Kentucky (80.8%), New Mexico (80%), Arizona (79.9%), and Arkansas (79.4%). The lowest shares were in Massachusetts (59.3%); Wyoming (59.9%); New Hampshire (60%); and Colorado, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania (all 62.2%).

Influence of federal policy changes

In recent years, changes in federal policies have significantly affected states’ financial responsibilities for Medicaid—and future federal actions are likely to continue shaping the extent of that budgetary pressure.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government offered states an enhanced Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP), the share of state Medicaid costs the federal government covers, on the condition that states were prohibited from removing individuals from their Medicaid programs. As a result, Medicaid enrollment surged—from 64.3 million in February 2020 to 87.1 million by April 2023, a 35.4% increase. But the Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA), which became effective March 31, 2023, marked the end of that continuous Medicaid enrollment requirement and allowed states to initiate unenrollment in April 2023. States had unenrolled more than 25 million people as of Sept. 18, 2024, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. The CAA also initiated the phaseout of enhanced federal matching funds that concluded in December. The enhanced FMAP, which was initially set to end on April 1, 2023, instead phased out gradually through the 2023 calendar year, decreasing to 5% on April 1, 2.5% on July 1, 1.5% on Oct. 1, and zero on Dec. 31.

The federal government also previously provided extra dollars to states to help cover increased costs of higher Medicaid enrollment and declining state tax revenue associated with the 2001 and 2007-09 recessions. As the enhanced federal aid from the 2007-09 Great Recession tapered off between December 2010 and June 2011, states’ share of Medicaid costs spiked while their tax revenue was still recovering.

Since January 2014, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has also provided an opportunity for states to expand their Medicaid programs with enhanced federal support. The law initially required states to expand Medicaid eligibility to all adults under age 65 who earn up to 138% of the federal poverty level, a change that the U.S. Supreme Court later ruled was optional for states. For states that chose to expand their coverage to this broader population, the federal government agreed to reimburse 100% of the expansion costs through 2016, then 95% of costs in 2017, and ultimately 90% from 2020 onward. As of the end of fiscal 2023, the time frame for this analysis, 39 states had expanded their programs in accordance with the ACA. North Carolina has also done so as of June 2025.

States that have expanded Medicaid coverage have typically drawn from their general funds to cover their share of the bill, and some have been able to offset the added costs with related budget savings, such as reductions in behavioral health spending. Several states also report using new or increased provider taxes and fees to help fund the expansion.

In 2006, the federal government began relieving states of prescription drug costs for “dual eligibles”— people who qualify for Medicaid and the federal Medicare program. In return, states must share some of their savings with the federal government through annual “clawback” payments, which are included in this analysis as part of state Medicaid spending.

However, the amount of federal reimbursement that states receive is just one of several factors that influence the wide range in the share of state’s own revenue spent on Medicaid. Among the other drivers are state Medicaid policy decisions—the breadth of health care services covered, eligible populations, and provider payment rates—and each state’s personal income levels. States with lower per capita income have higher federal reimbursement rates, and vice versa. The variation across states also is a function of tax and other policy decisions that determine state revenue and factors outside of policymakers’ direct control, such as state economic performance, demographics, resident health status, and regional differences in health care costs and practices. (For more information, see “ State Health Care Spending on Medicaid.”)

Moving forward, federal lawmakers are considering fundamental changes to Medicaid that could reshape its financing and shift more costs to state and local governments. Proposals include introducing per capita federal spending caps, lowering federal matching rates, converting Medicaid to a block grant structure, and imposing work requirements on certain adult enrollees. Although not all of these measures are likely to advance, they reflect a broader push to reduce federal spending. The effect of any changes will depend on their scope and design, but given Medicaid’s size and central role in state budgets, tens of millions of Americans could be affected, and fiscal pressures on states would likely grow.

States have limited short-term options to manage potential federal Medicaid cuts. Among the states that expanded Medicaid eligibility under the ACA, nine have laws that would require them to scale back expansion or make substantial program changes if the federal share of spending declines. Some states have also taken proactive steps to manage cost uncertainties: California and Indiana, for example, have established Medicaid- or health care-specific reserve funds to help cover unexpected costs. And more states are following suit. Idaho created a Medicaid Budget Stabilization Fund during its 2024 legislative session, and in 2025, New Mexico lawmakers approved a bill to establish and seed a Medicaid Trust Fund.

Why Pew assesses state Medicaid spending

State Medicaid spending has a significant impact on state budgets. As the largest expense for most states after K-12 education, Medicaid’s allocation from each revenue dollar directly influences the resources available for other key public services, such as education, transportation, and public safety. The federal government requires states to, among other things, provide matching funds to help cover the costs of Medicaid benefits for eligible enrollees, regardless of revenue conditions. This relative lack of state control over costs distinguishes Medicaid from many other programs and can be difficult for policymakers to navigate, especially when costs spike during economic downturns.

Justin Theal is a senior officer and Riley Judd is an associate on The Pew Charitable Trusts’ Fiscal 50 project.