How Record-Low Fertility Rates Foreshadow Budget Strain

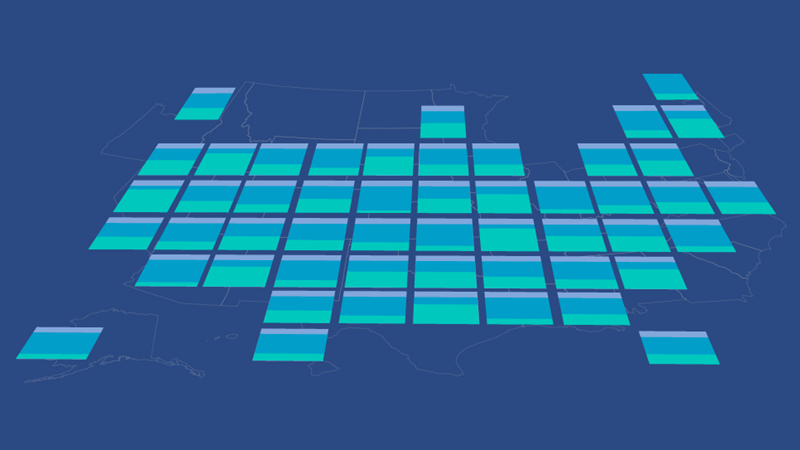

Every state saw declines in 2023 compared with the decade before the COVID-19 pandemic

Editor’s note: The analysis was updated on July 21, 2025, to reflect the years in which Arizona, Kentucky, and South Dakota recorded their lowest general fertility rates.

In 2023, 41 states and Washington, D.C. experienced their lowest fertility rates—the number of children born per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44—in more than 30 years, in line with a decades-long downward trend. In addition, 2023 marked a record low for the national fertility rate.

Historically, fertility rates have dipped during economic downturns but tended to recover as conditions improved. However, as discussed in The Pew Charitable Trusts’ 2022 brief, “The Long-Term Decline in Fertility—and What It Means for State Budgets,” that pattern broke after the 2007-09 Great Recession when fertility rates fell and never bounced back. The downward trend instead intensified in 2020 as the start of the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to a record annual drop nationwide. A slight rise in rates in 2021, which probably reflected births from pregnancies that women decided to delay during the early pandemic months, was short-lived, and the decline quickly resumed its long-running downward trajectory.

States have started to feel the budgetary effects of the long-term decline in fertility rates through reductions in some costs related to education and children’s health care programs. But related fiscal pressures are also creeping in. The first of the declining cohorts, those born in 2008, will reach adulthood in 2026, part of a gradual shift toward smaller working-age populations that may eventually shrink tax bases and limit revenue growth. State policymakers must reckon with the question of how best to navigate lower fertility rates and related fiscal impacts.

In 2023, the general fertility rate declined by 10.6% nationally to 54.5 from the 2011-20 average of 61. This means that approximately six fewer babies were born per 1,000 women in 2023 than over the decade ending in 2020.

Fertility rates fell in every state in 2023. Utah’s rate declined the most, by 20.8%, followed by New Mexico (-17.7%), Montana (-17.5%), Oregon (-17.2%), and Nevada (-17.2%). On the other end of the spectrum was New Jersey with a 4.2% drop—an almost five-times-smaller decline than Utah’s. Connecticut (-4.3%), Tennessee (-4.4%), and Alabama (-5.8%) also experienced some of the smallest decreases in 2023 compared with the pre-pandemic decade.

Regionally, the West recorded particularly steep drops, with a median decline of 16.4%. In fact, nine of the 10 states with the largest decreases were in the West.

The West’s drop in fertility rates in 2023 marks a pronounced shift. In the 2000s, the West boasted the highest median regional fertility rate, but by 2023, its rate had fallen to second-lowest. Although the region has experienced substantial population growth over the past several years, those gains were driven by an influx of people from other states and abroad rather than an increase in births.

Meanwhile, the Midwest and South recorded the highest fertility rates in 2023, jointly boasting 20 of the 25 states where rates were higher than the national general fertility rate. The Northeast recorded the lowest rate of any region in 2023, as it has consistently since at least 1990. All but one Northeastern state (New Jersey) ranked below the U.S. rate.

An analysis of states’ annual general fertility rates shows that:

- After the national general fertility rate posted its largest annual decrease in 30 years in 2020, it hovered at about 56 births per 1,000 women through 2022. And 2023’s drop to 54.5 births marked a continuation of the pre-pandemic downward trend.

- 41 states and Washington, D.C., recorded their lowest general fertility rates in more than 30 years in 2023.

- Of the remaining nine states, Arizona, Connecticut, Florida, Tennessee, and Texas hit their lowest rates in 2020, while Kentucky, North Dakota, South Dakota, and West Virginia hit theirs in the late 1990s.

- South Dakota recorded the nation’s highest general fertility rate in 2023, at 65.6 births per 1,000 women, followed by Nebraska (62.5), Alaska, (62.4), North Dakota (62), and Texas (60.6).

- Vermont’s rate of 42.1 was the lowest among states in 2023, with about 23 fewer births per 1,000 women than South Dakota. After Vermont were Washington, D.C. (43), Rhode Island (45.2), Oregon (45.9), and New Hampshire (46.8).

- Preliminary data for 2024 shows that the national general fertility rate ticked up by 0.2% from 2023, to 54.6.

Factors driving the fertility decline

In the decades leading up to the Great Recession, fertility rates were generally stable, fluctuating in tandem with economic cycles. But the failure of fertility rates to recover after the 2007-09 downturn marked a puzzling shift. Demographers have offered various explanations for why birth counts never rebounded, including that the declines since 2009 actually fit into a longer downward trajectory dating back to the 1800s and that U.S. fertility rates are following the path of those in other countries.

A range of changes in childbearing patterns help shed light on the causes of the fertility rate declines:

- The teenage fertility rate has been plummeting since the 1990s. Nationwide, the teenage general fertility rate in 2023 was down 41% from the average in the decade before the pandemic, nearly four times the decline of the total fertility rate. A Pew Research Center report cited greater awareness about (and use of) effective contraception, an increase in the number of teenagers who report never having had sex, and the Great Recession as factors.

- Hispanic fertility rates have also experienced a particularly noticeable drop-off since the Great Recession, falling from levels that have historically far exceeded those of non-Hispanic women to be more in line with other ethnic groups.

- Women are postponing having children until later in life than in past decades, which partially explains why fertility rates have dropped among women in their 20s and increased for women in their late 30s and 40s. The average age of a woman having her first child rose to 27.5 in 2023, a year later than during the pre-pandemic decade and two years later than in 2003. Although delayed childbearing could lead to only a temporary drop in the fertility rate, it can also result in fewer pregnancies over a lifetime, contributing to permanent declines.

However, although meaningful, these changes do not tell the full story. Women in general are having fewer children than previous generations for a range of economic and social reasons. Some of the major factors include:

- Financial concerns, such as widespread student debt, rising housing costs, and increased pessimism about future generations’ economic outlook, may be suppressing people’s desires to start or expand families, even though most young adults still say they want to have children. In addition, the high and growing costs of raising children—especially child care, education, and health care—may also be playing a role.

- Societal and cultural shifts, such as women reaching higher levels of educational and career attainment and couples marrying later in life, have also been linked to falling fertility rates. And an increasing share of U.S. adults report that they are unlikely to ever have children, often because “they just don’t want to,” “they want to focus other things, such as their career or interests,” or they have “concerns about the state of the world.”

Impact on state budgets

The decline in fertility rates is already rippling through state budgets. Many of the short-term fiscal effects may prove positive for states, but over time, these smaller birth cohorts may create broader challenges. In the near term, fewer children may lead to cost savings for states in several areas, especially health care and education. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the sharp reduction in teenage pregnancies has already saved taxpayers billions in reduced spending in programs that teenage mothers and their children tend to rely on, such as Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program.

Further, smaller birth cohorts mean fewer students, which translates to cost savings for states even as other K-12 spending pressures increase and falling enrollment creates challenges for funding formulas. In Minnesota, for example, reduced pupil counts helped offset rising expenditures on special education and nutrition programs.

Higher education may experience a similar dynamic as the first cohort born during the Great Recession heads off to college starting in 2026. A recent Colorado long-term budget assessment warned of “a much-anticipated upcoming enrollment cliff,” which means fewer tuition dollars and could lead to financial difficulties for state-funded higher education institutions.

However, the complicated nature of higher education enrollment trends makes projections difficult. For example, enrollment is also affected by students’ decisions about whether to attend college and migration of students from other states and abroad, which create additional uncertainty. This can lead to competing forecasts, such as the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education projecting a steady decline in college-age students from 2026 through 2041, while the National Center for Education Statistics estimates that total undergraduate enrollment will grow through 2031.

In addition, low fertility rates correspond with increased labor force participation among women, which yields greater tax collections. But they also portend slower workforce growth over the next several decades, which could lead to slowed or declining tax revenue growth as fewer workers pay income taxes and make purchases that generate sales taxes. States that depend heavily on personal income and sales taxes are at greater risk than those that generate substantial revenue from sources that are less tied to population, such as severance taxes.

A smaller workforce will also indirectly affect revenue through slower economic growth. In a recent budget forecast, Montana highlighted that “anemic growth among the younger age cohorts in Montana is troublesome for the future of the prime working age population and by extension economic growth.” Additionally, a shrinking working-age population could mean less domestic innovation and productivity and decreased per capita income in many states.

Beyond their effects on states’ tax revenue and economies, dropping fertility rates could reduce the amount of federal funding states receive. Several major federal programs—including Title I grants and other education programs, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and Head Start—allocate money to states according to formulas that incorporate population counts, meaning that states with the largest birth rate (the number of live births per 1,000 people in a given population) declines may also see the largest decrease in federal funds. Furthermore, the Department of Transportation has indicated an interest in prioritizing state funding for communities with marriage and birth rates that exceed the national average rather than based on formulas tied to population counts, as has been traditional.

The shifting demographic landscape

The decline in fertility rates goes hand in hand with other, concurrent demographic considerations facing states, such as the increased role of domestic and international migration in population growth and an aging population.

Migration is emerging as the most significant determining factor for state population change as birth rates stagnate; in 2024, it became the primary driver of growth in every state except Alaska. Attracting residents from other states or abroad may help states overcome reduced fertility levels and boost their overall populations.

Additionally, the aging population poses a growing challenge for states, compounding the effects of declining fertility. Although birth rates started consistently falling around the beginning of the Great Recession, the decreasing number of children since then pales in comparison to the rapidly growing number of Americans in their 60s and 70s, and states are already contending with additional costs of health care and long-term care for these older residents. That trend and the exit of baby boomers from the workforce could further limit revenue growth and add to fiscal uncertainty.

Mapping out demographic shifts and understanding the myriad factors contributing to the decline in fertility rates can help state policymakers identify strategies to address the immediate and long-term challenges. Demographic outlooks, such as this one conducted by Pennsylvania’s Independent Fiscal Office, can better equip states to assess the long-term impacts of the fertility decline on their economic conditions and state trends. For instance, Michigan’s population projections through 2050 explain that while “substantial population growth from natural increase is unlikely in the foreseeable future,” positive net migration may negate those negative effects for at least another five to 10 years.

States may also consider including demographic and population information in their budget conversations—as North Carolina did in its fiscal 2025-27 budget—as they plan for the fiscal ramifications of an aging population. Additional demographic trends affecting the total population, such as migration and life expectancy, should also be included in any assessment of a state’s long-term fiscal outlook.

Conclusion

The effects on state budgets of the continued decline of the general fertility rate are already starting to materialize and will only intensify over the next several years. Although some states are seeing temporary savings on children’s health care and K-12 spending, decreasing fertility rates are likely to eventually translate into declining revenue and an aging workforce. States should be looking now for ways to prepare for these challenges. Conducting long-term demographic outlooks and incorporating population projections into budgets can help them identify trends and risks specific to their conditions.

In times of fiscal instability, thinking beyond the immediate budget cycle can be difficult. However, states must also look to the future and be prepared for slumping fertility rates and other coming demographic shifts.