Cost for Repairs to U.S. Transit Assets Estimated at $140.2 Billion

Federal report highlights major investment needs for nation’s public transit systems

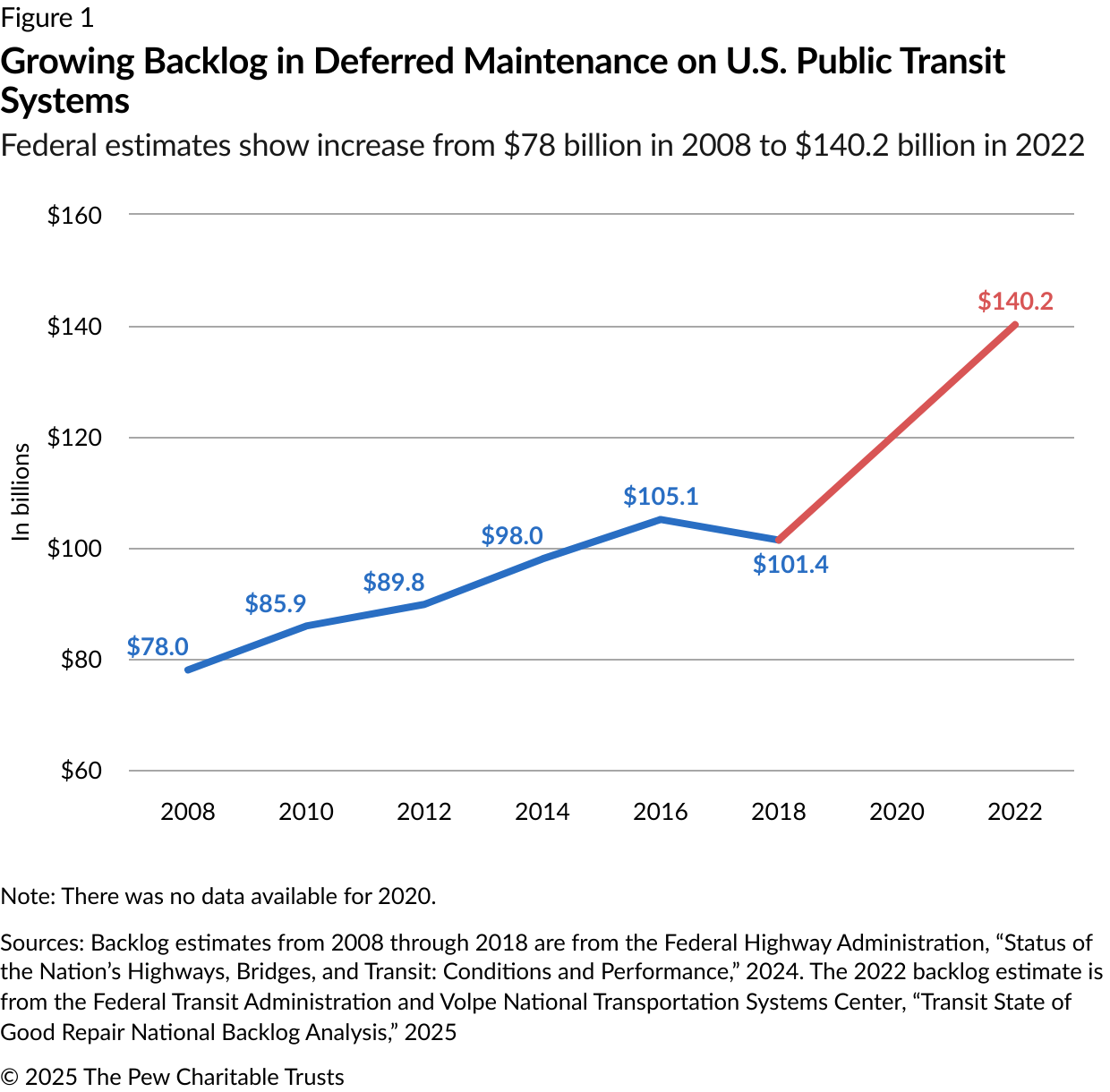

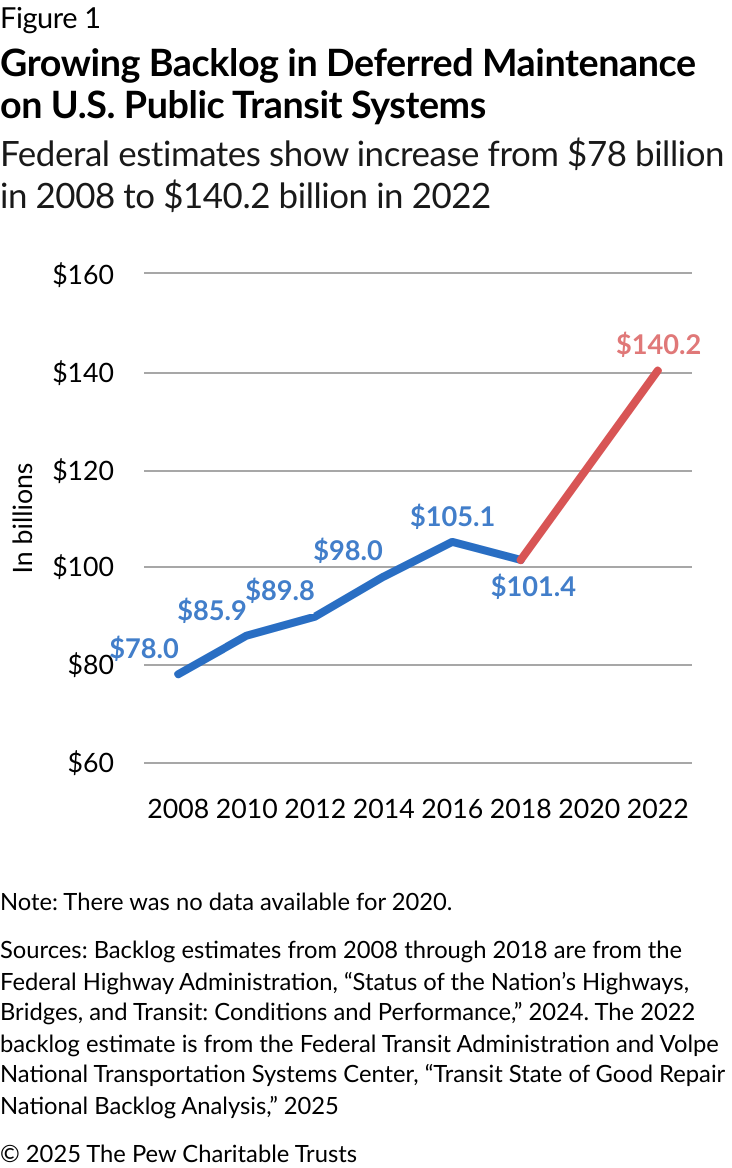

A recent report from the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) and the Volpe National Transportation Systems Center indicates that the nation’s essential public transit systems, including buses, trains, and other vehicles, face a growing crisis: a $140.2 billion backlog of needed infrastructure improvements, repairs, or upgrades to ensure they operate safely and efficiently. That’s up from an $101.4 billion estimate in 2018.

The report released in January highlights how decades of underinvestment, rising inflation, and aging systems have compounded to create a funding gap that threatens the reliability and safety of these transit systems that move millions of riders daily.

The expanding backlog

As of 2022, the latest year for which data is available, the FTA reports that the total value of U.S. transit assets was roughly $1.3 trillion. The FTA, which provides financial and technical assistance to local public transit systems, estimates that about 10% ($140.2 billion) of those assets needed additional funding. This additional money is necessary to repair, maintain, or replace transit assets to ensure safe and working conditions, also known as a state of good repair (See Figure 1.) This represents a $38.8 billion increase in required investments since the FTA’s 2018 report on the status of the nation’s transit systems. In total, roughly one-tenth of the U.S. transit infrastructure required significant reinvestments to achieve a state of good repair.

The report identifies four key factors driving the rapid backlog growth. Inflation accounts for nearly half (48%) of the increase, as rising costs for materials, labor, and delays in completing transit infrastructure projects drove up expenses. The expansion of new tracks, tunnels, and bridges— referred to as guideway elements—accounts for 16% of the increase, as agencies across the country have expanded their transit networks, often without planning for long-term maintenance funding. Changes to inventory information, including new data on certain assets and facilities, was responsible for 16% of the increase. Finally, the 2025 analysis slightly updates how transit asset costs are calculated, resulting in higher estimated costs for the same assets and a larger overall backlog.

Which assets are in the worst condition?

While transit systems nationwide are aging rapidly, certain components of the infrastructure are in far worse condition than others. The National Transit Database tracks the finances, operations, and conditions of nearly 3,000 transit agencies as of 2022. The model analyzes the data to estimate the age, condition, and value of transit assets, including vehicles, facilities, and rail infrastructure.

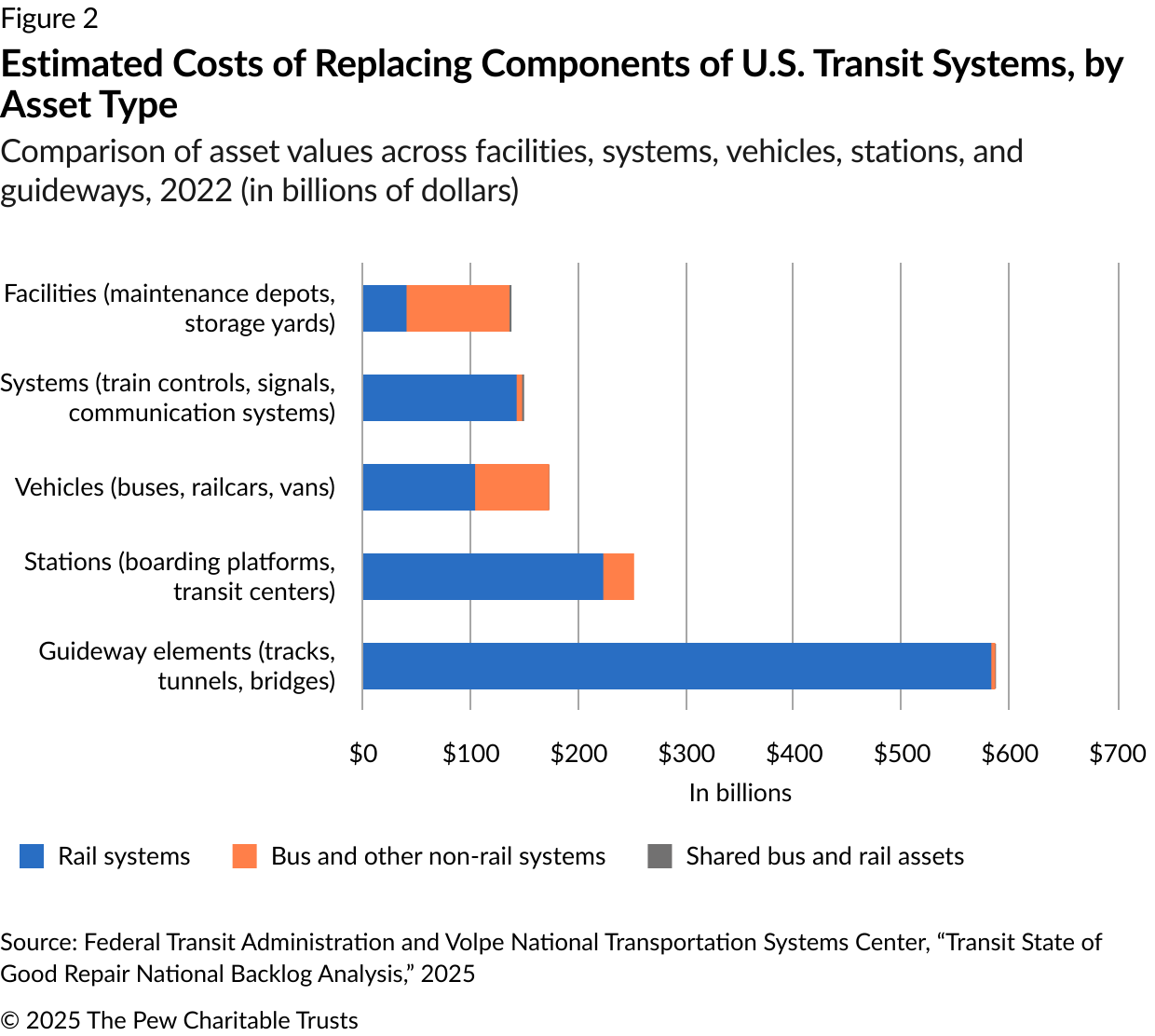

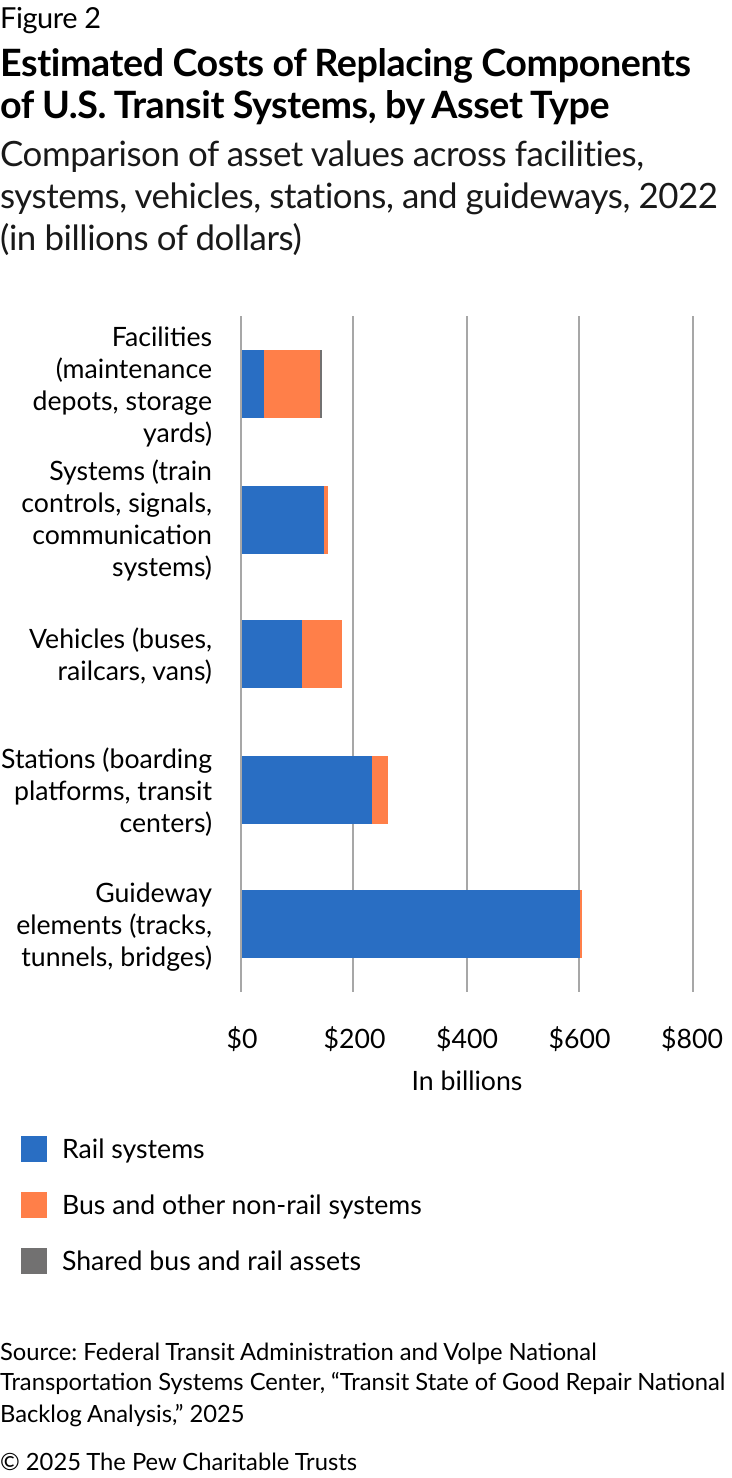

The FTA’s backlog analysis categorizes transit infrastructure into five main components so these analyses can be used to identify where reinvestment is most needed:

- Guideway elements: structures that guide transit vehicles, such as tracks, tunnels, bridges, and dedicated bus lanes.

- Stations: passenger boarding areas, including buildings, platforms, transit centers, and other access points.

- Vehicles: transit fleet vehicles, such as buses, railcars, and vans for passenger transport.

- Facilities: buildings for maintenance and operations, including storage and repair facilities.

- Systems: operational infrastructure for train control, safety, and communication networks, including signaling and fare collection systems.

Across these categories, the systems assets are in the worst conditions, with 21.7% rated to be in “poor” condition. That’s more than double the rate of the other infrastructure types. Without targeted reinvestments, deterioration of these critical systems poses a significant safety and reliability risk for transit agencies nationwide.

The FTA report also provides estimates of the cost to replace failing components to bring assets out of “poor” condition and into a state of good repair. (See Figure 2.) The most expensive components to replace are guideway elements, almost entirely on rail systems, which cost roughly $600 billion to replace across the nation. This is followed by stations, also primarily for rail (less than $300 billion total), and then vehicles, which are split evenly between rail and bus systems (less than $200 billion total).

Shifting maintenance challenges for transit vehicles

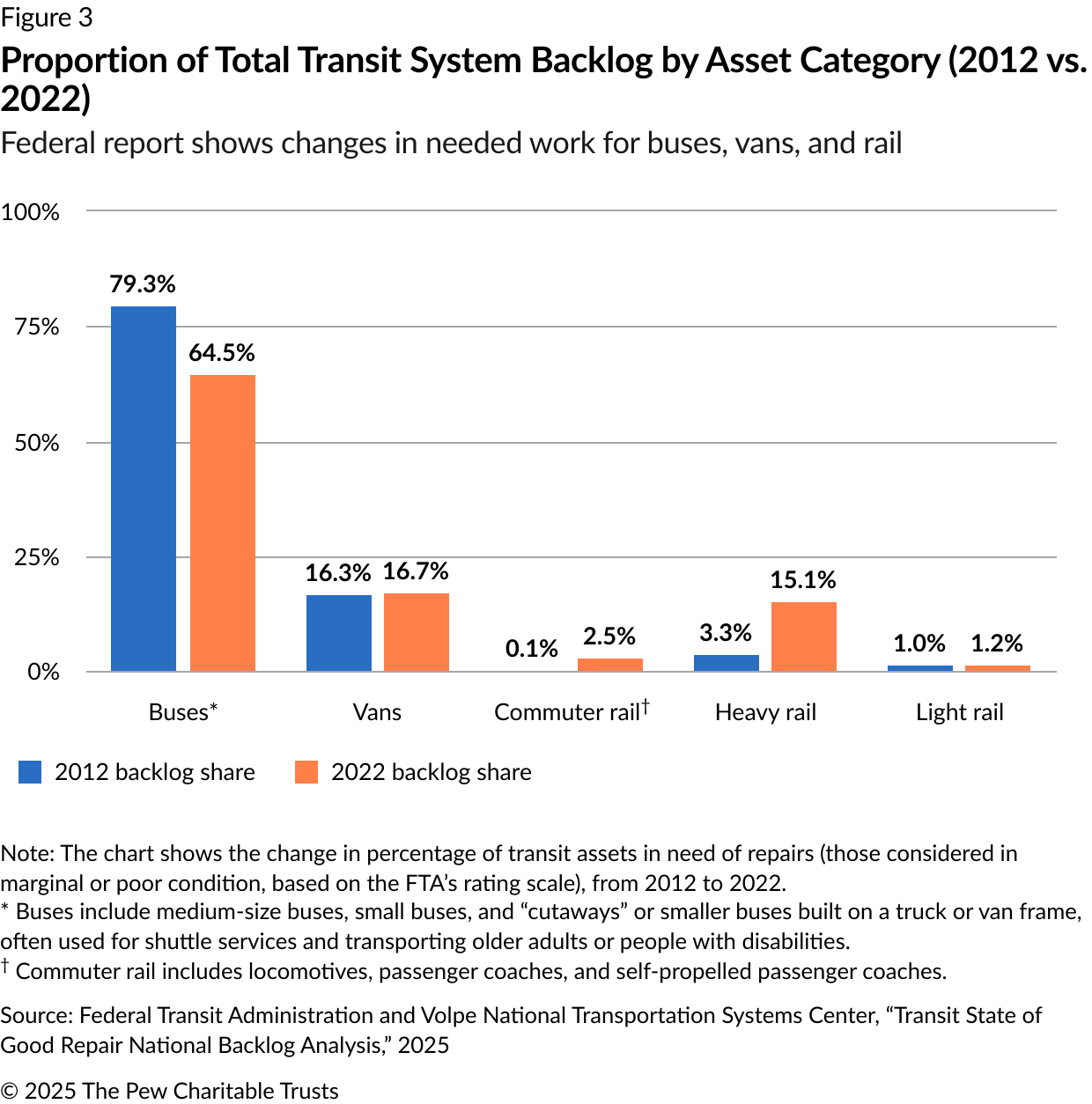

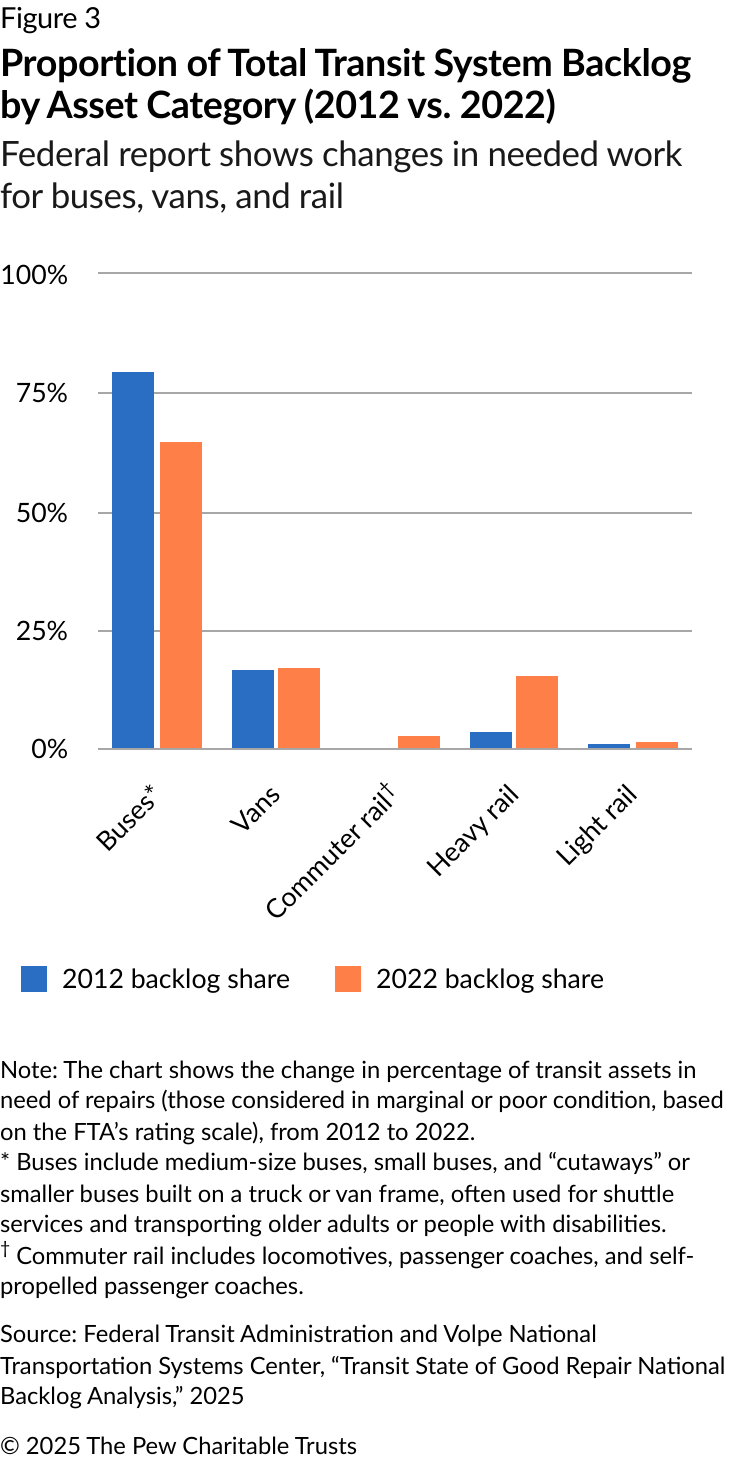

A closer look at transit vehicles—critical components of any transit network that are subject to significant wear and tear from daily operations—reveals new and shifting challenges in maintaining them in a state of good repair. Although buses in need of repair still make up the largest share of the backlog in this category, their portion declined from 79.3% in 2012 to 64.5% in 2022. Despite agencies having made progress in replacing or repairing aging fleets, buses remain the largest area of deferred maintenance needs. (See Figure 3.) Part of the improvement, meanwhile, can be attributed to the approximately $5 billion in formula and competitive grants from the 2021 bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA). That money was designated to help local governments rehabilitate, replace, or purchase new buses and related equipment. An additional $5.5 billion in competitive grants from the IIJA also supports these governments seeking to purchase low or no emission buses.

In contrast, the percentage of heavy rail needs in the backlog more than quadrupled, growing from 3.3% to 15.1% over that same period. As of 2022, that work made up a much larger portion of the overall backlog. The numbers show that nearly 30% of subway or metro trains nationwide are in poor or marginal condition and in need of major repairs or replacement.

The report also indicates growing issues with the maintenance of commuter rail systems, which include engine-powered trains (locomotives), passenger coaches, and train cars with built-in motors (self-propelled passenger coaches) that serve riders traveling between cities and suburbs. In 2012, this category made up roughly 0.1% of the overall transit backlog, but by 2022, its share grew to 2.5%.

Upgrade needs for vans, used to provide transit services for seniors and people with disabilities, saw a slight increase in the backlog, from 16.3% to roughly 16.7%. Light rail, which includes streetcars and tram systems, remains a smaller part of the backlog, with needs rising slightly from 1% to 1.2%, but the percentage of vehicles in poor condition grew from 6% to 10%, indicating growing maintenance needs.

Overall, the focus of the backlog problem is shifting. Although buses still account for the largest share, their overall backlog is declining, while maintenance needs for rail vehicles—especially subways, metro trains, and commuter trains—are growing rapidly, making up a larger share of the problem. These issues are playing out nationwide: New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority continues to struggle with soaring maintenance and repair costs. In New Jersey, aging infrastructure has led to persistent train delays. And Denver’s Regional Transportation District recently shut down a major section of its downtown light rail service to address long-overdue maintenance. Without targeted reinvestment, these issues will continue to threaten the reliability and sustainability of transit networks.

Balancing replacement, expansion, and maintenance

Although rail systems face the most pressing maintenance issues, bus networks are still struggling. In South Florida, for example, an electric bus fleet that cost $126 million has faced major operational issues, with only a handful of the vehicles running because of maintenance backlogs. Meanwhile, budget constraints in Philadelphia have stalled a planned overhaul of the city’s bus system, worsening service gaps and delays. These cases highlight how deferred investments are limiting agencies’ ability to provide reliable service.

California faces similar challenges, balancing costly maintenance needs with a major transit expansion ahead of the 2028 Olympics in Los Angeles. At the same time, agencies in the state, such as the Bay Area Rapid Transit system and Caltrain, are dealing with financial shortfalls and declining ridership as pandemic-era federal funding runs out. In response, state lawmakers have proposed a $2 billion investment to improve bus and rail networks throughout the state.

The FTA and Volpe report highlights the growing gap between funding and maintenance needs. While the IIJA provided a major increase in federal transit funding, most of it is limited to large-scale capital projects. Without more flexible, sustained investment, agencies will struggle to keep aging infrastructure in working order, putting reliability and service at risk for millions of riders.

Claire Lee is a senior associate, Fatima Yousofi is a senior officer, and Elijah Gullett is an associate working on The Pew Charitable Trusts’ state fiscal policy project.