An Increase in Pension Obligations Adds to States’ Unfunded Liabilities

Since 2008, public pensions have persistently remained the largest of the three long-term obligations that states regularly report on, even as the burden from outstanding bond debt and retiree health care has eased. Nationwide, unfunded pension liabilities—the gap between the amount needed to pay for promised pension benefits and the amount set aside for them—grew to nearly $1.3 trillion in fiscal year 2022, largely because of lower-than-expected investment returns. The pension funding shortfall increased almost 17 percentage points from the previous fiscal year, to nearly 66% of states’ own-source revenue (all taxes and fees levied and collected directly by the state in 2022). By contrast, the burden from outstanding debt declined as a percentage of state revenues in fiscal 2022. The third major source of long-term state liabilities, unfunded retiree health care, fell in fiscal 2019 (the most recent year for which The Pew Charitable Trusts has compiled 50-state data).

Long-term liabilities are not always top of mind for state policymakers because they are paid for over decades. Yet, when they grow faster than a state’s revenue, those liabilities can squeeze state budgets and constrain future public investments.

Of the three types of long-term liabilities that states regularly report on, unfunded pension obligations are the biggest in most states, followed by unfunded retiree health care and outstanding debt. Pension shortfalls are typically caused by insufficient funding and underperforming investments, among other factors. States tend to set aside less money for retiree health care liabilities, as a percentage of overall obligations, than for pension debt. Instead, they often pay retiree health care costs directly out of current revenue, meaning that the entire liability is unfunded.

On the other hand, states repay outstanding bond debt according to a fixed repayment schedule. Using bonds to finance major infrastructure projects, such as the replacement of aging wastewater treatment plants, spreads the cost across the generations of taxpayers who will benefit and frees up cash to cover current expenses. It is critical that policymakers carefully consider all of their states’ existing obligations when assessing how much additional debt to take on.

Trends in unfunded liabilities

In fiscal year 2022, losses on stock market investments fueled a jump in the funding gap for state pension plans. States collectively reported $1.27 trillion in unfunded pension benefits in fiscal 2022, equal to nearly 66% of their combined own-source revenue—almost 17 percentage points higher than just a year earlier.

By historical comparison, unfunded pension commitments as a share of all states’ own-source revenue have grown by nearly 23 percentage points since fiscal 2008. Investment losses during the Great Recession of 2007-09 lowered plan assets, causing a rise in unfunded liabilities. In the aftermath of the Great Recession and throughout much of the ensuing recovery, the funding gap continued to grow as a result of a combination of factors: insufficient contributions, lower-than-expected investment returns, pension funds making more conservative assumptions about future investment returns, and, in some cases, benefit enhancements that were not accompanied by sufficient funding to pay for the increased liability. In fiscal 2021, once-in-a-generation returns on stock market investments, following multiple years of substantial increases in state employer and employee contributions, allowed state pension funds to collectively narrow the gap between what they had set aside and what they owed in benefits. But investment losses in fiscal 2022 widened the gap again, underscoring the ongoing risk that volatile financial markets pose to state and local governments.

Unfunded retiree health care promises (which make up the vast majority of “other post-employment benefits,” or OPEB) declined as a share of states’ combined own-source revenue from 53.1% in fiscal 2008 to 45.4% in fiscal 2019 as growth in 50-state revenue outpaced a rise in OPEB underfunding. In raw dollars, however, unfunded retiree health care promises rose over this span, reaching $680 billion in fiscal 2019, the most recent year for which Pew has compiled data. The drivers of this growth are difficult to pinpoint because of a change in accounting standards (which also led to a gap in the data for fiscal 2017); limited data disclosed under the prior reporting requirements; and changes to benefits and contribution policies.

The 50 states’ combined debt burden declined in fiscal 2022 to its lowest point in 15 years. Outstanding debt as a share of own-source revenue dropped to 18.3%, nearly 7 percentage points below the fiscal 2008 level. After borrowing more heavily during the Great Recession, states kept their combined debt relatively stable, in dollar terms, because policymakers were cautious about issuing bonds. As with retiree health care, the share of outstanding debt relative to states’ own-source revenue declined, largely as a result of growth in revenue over the years, especially in fiscal 2022. States had a combined $326 billion of debt in fiscal 2022—a higher amount than in previous years—but the share as a percentage of revenue still fell because of an increase in total revenue.

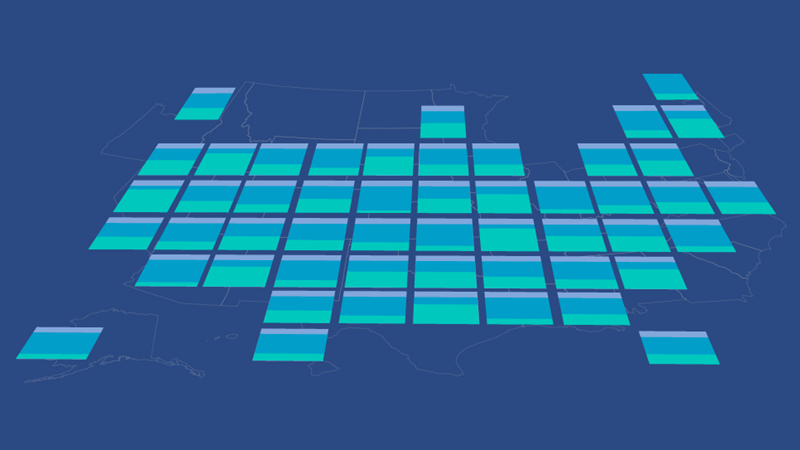

A state-by-state review of unfunded pension liabilities as of fiscal 2022 shows:

- Illinois’ unfunded pension liability was the largest of any state at 197.2% of its own-source revenue, followed by New Jersey (162.4%), Mississippi (149.5%), Connecticut (147.6%), and Kentucky (134.9%).

- Pension plan assets in fiscal 2022 exceeded what was owed in four states: New York, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Washington.

- In 34 states, unfunded pension obligations grew relative to own-source revenue from fiscal 2008 to fiscal 2022. Five states recorded increases of 60 percentage points or more in that time span: Alaska (increased by 93.1 points), New Jersey (+77.9 points), Georgia (+69.5 points), Florida (+62.7 points), and Pennsylvania (+60.0 points).

- Sixteen states have decreased their unfunded pension liabilities as a share of own-source revenue since 2008. Oklahoma (53.4-point decrease), West Virginia (-38.2 points), and Oregon (-37.1 points) had the greatest declines.

A state-by-state review of unfunded retiree health care as of fiscal 2019 shows that:

- Unfunded retiree health care liabilities as a share of own-source revenue were highest in New Jersey (139.4%), Illinois (136.5%), Delaware (109.9%), Connecticut (103.2%), and Texas (98.1%).

- Alaska, Arizona, and Oregon were the only states whose retiree health plans had a surplus of assets relative to what they promised public workers.

- Four states owed less than 1% of own-source revenue: Utah (0.42%), Indiana (0.49%), Kansas (0.54%), and Oklahoma (0.64%).

- Since fiscal 2008, unfunded retiree health care liabilities relative to own-source revenue grew fastest in Illinois (by 34.3 percentage points) and Texas (+29 points).

- In 36 states, unfunded obligations have declined as a share of own-source revenue since fiscal 2008. The largest decreases were in Alabama (-79.8 percentage points), Alaska (-74.8 points), and Michigan (-72.6 points). Alaska and Michigan both set aside billions of additional assets toward pre-funding retiree health care obligations.

- Nebraska does not report its retiree health care liability, and South Dakota stopped reporting its liability for retiree health care in 2014 and does not currently offer these benefits.

A state-by-state review of debt as of fiscal 2022 shows:

- The highest debt levels were in Connecticut (equivalent to 69.5% of own-source revenue), Hawaii (60.8%), and Massachusetts (46.7%).

- Debt as a share of own-source revenue was lowest in Iowa (0.3%), Nebraska (0.8%), and South Carolina (1.3%).

- Debt grew in 12 states between fiscal 2008 and fiscal 2022 when measured as a percentage of own-source revenue. The largest increases were in Alaska (+14.5 percentage points), Colorado (+13.4 points), Delaware (+7.3 points), and Wyoming (+3.0 points).

- Among the 37 states with declines in debt as a share of own-source revenue since fiscal 2008, the largest decreases were in California (-21.3 percentage points), New Jersey (-20.9 points), Nevada (-17.1 points), and Illinois (-14.5 points). Data is unavailable for New York.

Changes in annual funding needs

Nationally, the amount needed to adequately fund state pension plans in fiscal year 2008 was 5.9% of own-source revenue. That share increased to 7.8% in fiscal 2021 before dropping to 4.9% in fiscal 2022. The increase from fiscal 2008 to fiscal 2021 was driven by investment losses from the Great Recession, the need to make up for past contribution shortfalls, the adoption of more realistic assumptions, and changes in government accounting standards. From fiscal 2021 to fiscal 2022, the reduction in necessary annual pension contributions was due to strong investment performance in fiscal 2021, which improved the funding of public pension plans. Subsequent investment losses in fiscal 2022 erased much of the fiscal 2021 increase. As a result, the contribution benchmark for pension plans is expected to rise when data for fiscal 2023 becomes available.

In fiscal 2008, more than half of states set aside less than what their actuaries had calculated was necessary to adequately fund public pensions, with a combined pension contribution of 5.3% of state revenue instead of the 5.9% that was needed. By 2013, the contribution amount recommended by plan actuaries had risen to 7.8% of state revenue; actual contributions likewise rose in that period, to 6.2% of state revenue, but remained short of projected needs.

In 2014, new accounting standards resulted in a contribution benchmark of 9.4% of state revenue to avoid increases in pension debt. Over time, policymakers significantly boosted the share of state resources going into public pension plans, with actual contributions for all 50 states catching up to the benchmark by fiscal 2019 and significantly exceeding it in fiscal 2022. Managing this increase required fiscal discipline and tough choices, as the rise in contributions crowded out other spending priorities but meant that states were no longer collectively leaving the cost of unfunded liabilities to future generations.

Nationwide, the contributions needed to fund retiree health care benefits stayed relatively stable as a share of own-source revenue, dropping from 4.3% in fiscal 2008 to 3.5% in fiscal 2019. Actual contributions to state retiree health care plans, however, consistently fell short of those levels, totaling only about 1.5% of state own-source revenue in fiscal 2008 and fiscal 2019.

In the 50 states, the combined annual cost to service outstanding debt relative to own-source revenue grew slightly during the 2007-09 recession but fell between fiscal 2008 and fiscal 2022, from 3.7% to 2.8%. Although the overall cost of debt service, in dollar terms, rose during this period, own-source revenue grew at a faster pace. South Carolina, California, Nevada, and New Mexico experienced the greatest declines in debt service payments as a share of own-source revenue. At the other end of the spectrum, the relative cost of debt service increased in 10 states over this 15-year period. Only Alabama, Alaska, and Hawaii’s payments increased by more than 1 percentage point as a share of own-source revenue.

In fiscal 2022, contributions to state pension plans nationally exceeded Pew’s net amortization benchmark by approximately $61 billion. This benchmark measures whether employer contributions were sufficient to keep pension debt from growing on an annual basis (provided plan assumptions are met). To achieve this goal, contribution amounts must cover pension benefits that current state employees are earning and either reduce or hold flat any unfunded liabilities already on the books.

Strong investment returns in fiscal 2021 lowered the net amortization benchmark in fiscal 2022, as there is a one-year lag between changes to plan funding and changes to the necessary cost of funding benefits. Windfall investment yields cut the aggregate funding gap by $548 billion at the start of fiscal 2022, which in turn lowered the benchmark by $37 billion. As a result of those investment gains and other factors, the amortization benchmark fell from $133 billion in fiscal 2021 to $94 billion a year later. However, the 2023 benchmark is expected to increase, as 2022 investment losses undid much of the 2021 gains.

Because the benchmark is subject to investment volatility, assessing contribution adequacy over time can help clarify the picture of plan sustainability. From fiscal 2018 through fiscal 2022, 36 states had positive amortization, meaning they made contributions that were large enough to pay down pension debt. Another four had stable amortization, meaning that the difference between contributions and the benchmark was within .5% of payroll. In those states, payments were adequate to prevent pension debt from growing. And 10 states’ contributions were insufficient to cover benefits and interest over that four-year period, resulting in negative amortization and growing pension debt.

States made less progress in meeting the contribution levels necessary to keep retiree health care debt from growing. In fiscal 2019, the most recent year for which Pew compiled the data, only 10 states met or exceeded the target: Arizona, Idaho, Indiana, Michigan, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, Utah, and Wisconsin. The gap between the actual contribution and the benchmark was greatest in Texas, followed by California, New Jersey, and Illinois.

For states with significant retiree health care liabilities, adequate funding ensures that future generations do not have to pay for services being provided today and that money is set aside for benefits that retirees are counting on. If states continue to fund below the necessary threshold, they will face growing debt for retiree health care benefits and associated pressure on their budgets.

Differences among payment practices

States typically are legally bound to keep their pension benefit promises, though their annual contributions may fluctuate, causing them to fall behind in paying down unfunded liabilities. States vary in whether they set contribution rates to match actuarial requirements or have a statutorily fixed contribution rate that may fall short of funding needs. Even states that apply actuarial funding may suspend adequate funding because of budget concerns or follow a policy that pushes the bulk of the costs to future generations.

On the other hand, many states fund retired employees’ health insurance on a pay-as-you-go basis, though some have committed to pre-funding future retiree benefits. Public retiree health care benefits have fewer legal protections than pensions do, though political or social considerations may also prevent states from reducing these benefits.

States usually cover their annual debt obligations before other long-term expenses in accordance with constitutional or statutory requirements. They also face other long-term budget pressures, such as expenses for deferred maintenance and upgrades to infrastructure. But state budgets generally do not account for these future costs.

For more information, see Pew’s analysis “As Pension Funding Levels Fell in 2022, Higher Contributions Helped States Manage Debt” and issue brief “Do States Have Enough Saved for Retiree Health Care Benefits?”

Why Pew Assesses Long-Term Liabilities

Failing to manage long-term liabilities—whether public debt, retirement promises, or other bills—can hamper states’ ability to make needed investments and provide critical services to future generations. Pew tracks reported data that shows the magnitude of states’ long-term liabilities and the costs to manage them as a share of state revenues.

David Draine is a principal officer and Keith Sliwa is a principal associate with The Pew Charitable Trusts’ public sector retirement systems project; Joanna Biernacka-Lievestro is a senior manager and Riley Judd is an associate with Pew’s Fiscal 50 project.