Co-Living Buildings in Albuquerque and Santa Fe Could Improve Housing Affordability

Shared housing model offers lower-cost option to address housing shortage in New Mexico’s cities

In cities throughout the United States, residential rents and homelessness are soaring while downtown office space sits vacant, hinting of a solution that has mostly remained out of reach. The challenge is particularly acute in New Mexico, where both rents (+60%) and homelessness (+87%) rose more than twice as fast as the national averages from 2017 to 2024 (27% and 40%, respectively). But a new analysis from The Pew Charitable Trusts and the global architecture, design, and planning firm Gensler points toward an approach that could address all of those problems at once: Albuquerque and Santa Fe could add hundreds of low-cost homes and curb homelessness with small, dormitory-style microapartments that have shared kitchens, bathrooms, and amenities. The Pew/Gensler study found that each “co-living” apartment would cost about $130,600 to build in Albuquerque and $184,400 in Santa Fe, well below the roughly $300,000 needed to build a typical studio apartment.

Like much of the U.S., New Mexico is experiencing a severe housing shortage, driven primarily by years of underproduction. The state added just 2.9% to its housing stock from 2017 to 2023, far below the 9.4% added nationwide in that six-year period. And even that 9.4% was nowhere near enough: The U.S. has an estimated shortage of 4 million to 7 million homes.

At the same time, Albuquerque has a number of underused office buildings in its central business district. The downtown office vacancy rate in the first quarter of 2025 was 24%, higher than the national average of 20%. Ever since the COVID-19 pandemic emptied U.S. office buildings, housing advocates have suggested that these underused offices might provide at least a partial solution to the country’s housing shortage. But conventional office-to-apartment conversions are usually too expensive to be economically feasible in all but the highest-rent U.S. cities, in large part because of the cost of extending centralized plumbing to every apartment and replacing office-style, fixed windows with ones that can be opened.

Co-Living Model Can Enable Cost-Effective Development

Working first in larger cities (such as Los Angeles, Houston, and Chicago), Pew and Gensler have examined a new approach to development, which could quickly add a significant number of new, low-cost microapartments near existing transportation, jobs, and stores. Instead of converting office buildings to conventional apartments, developers could instead turn them into dorm-style housing, with small, private, furnished microapartments lining the building’s perimeter. Shared kitchens, bathrooms, living rooms, and laundry facilities would be located at the building’s core—where office plumbing is already located. Key cards could be used to limit access to each floor, promoting community and improving safety.

This model is also efficient. It produces about three times as many homes as a conventional office-to-apartment conversion, at a cost that is 25% to 35% lower per square foot. In Albuquerque, the Pew/Gensler report describes the conversion of a five-story, 92,000-square-foot building that would yield 256 microapartments on the second through the fifth floors; including 16 double rooms, it could house 272 people. The projected cost per unit would be approximately $130,600—less than half the roughly $300,000 needed to build a studio apartment in New Mexico’s largest city.

With a projected rent of $700 per month, the cost of these co-living apartments would be well below Albuquerque’s median rent of $1,200 per month. They would be affordable to a person earning about 45% of the area’s median income. The projected net operating income (cash flow) for this model conversion suggests that an upfront subsidy of about $65,000 per unit would be needed to make it profitable enough for developers to build. But no ongoing subsidy would be needed. By contrast, a similarly affordable new studio apartment in Albuquerque would require a subsidy of about $235,000.

New Construction in Santa Fe

Santa Fe posed a different challenge. New Mexico’s capital has no tall office buildings, so the Pew/Gensler team examined the cost of developing a new, three-story building with 60 microapartments near existing transportation routes and businesses. In this model, shared facilities—kitchens, two living areas, and a central laundry—would be located on the ground floor, along with 12 ADA-accessible apartments. The upper floors would contain 24 apartments apiece (20 singles and four doubles) as well as shared bathrooms.

Even with new construction, the estimated cost per unit—$184,400—was significantly lower than the $300,000 cost of a new studio apartment. The projected rent of $800 per month is far below both Santa Fe’s current median rent for a market-rate apartment (nearly $1,500) and the average cost of a studio apartment ($1,147). At $800 per month, these new, furnished homes would be affordable to someone earning some $32,000 per year, about 46% of the area’s median income.

One virtue of this Santa Fe model is that it’s scalable. And it could work in other small cities without half-empty high-rises ripe for conversion. The 60-unit building described above would fit on 0.6 acres (in Santa Fe, six to seven city lots); a 0.8-acre parcel of land—roughly nine city lots—could fit 96 microapartments. With a small number of larger, double apartments, this larger building could house 112 people. These new microapartments would likely be located near a shopping center or other commerce, rather than on a single-family block.

As with Albuquerque, however, even this low-cost co-housing would need public subsidies to attract the interest of (and investments from) private developers. The Pew/Gensler team estimated that the Santa Fe model would require an upfront subsidy of about $100,000 per unit. Again, that’s far below the subsidy of more than $200,000 per unit that would be needed to build a similarly affordable studio apartment in Santa Fe.

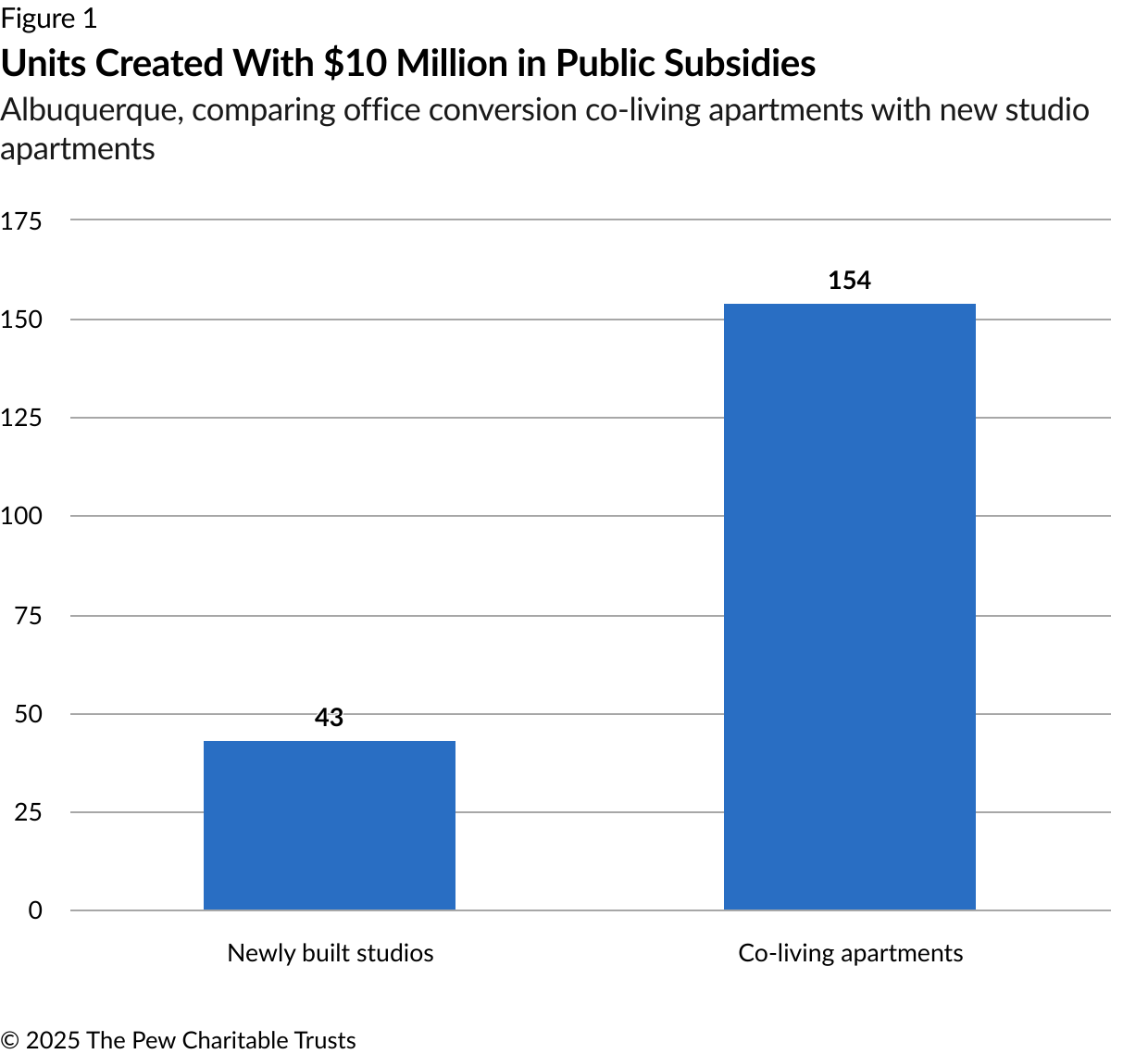

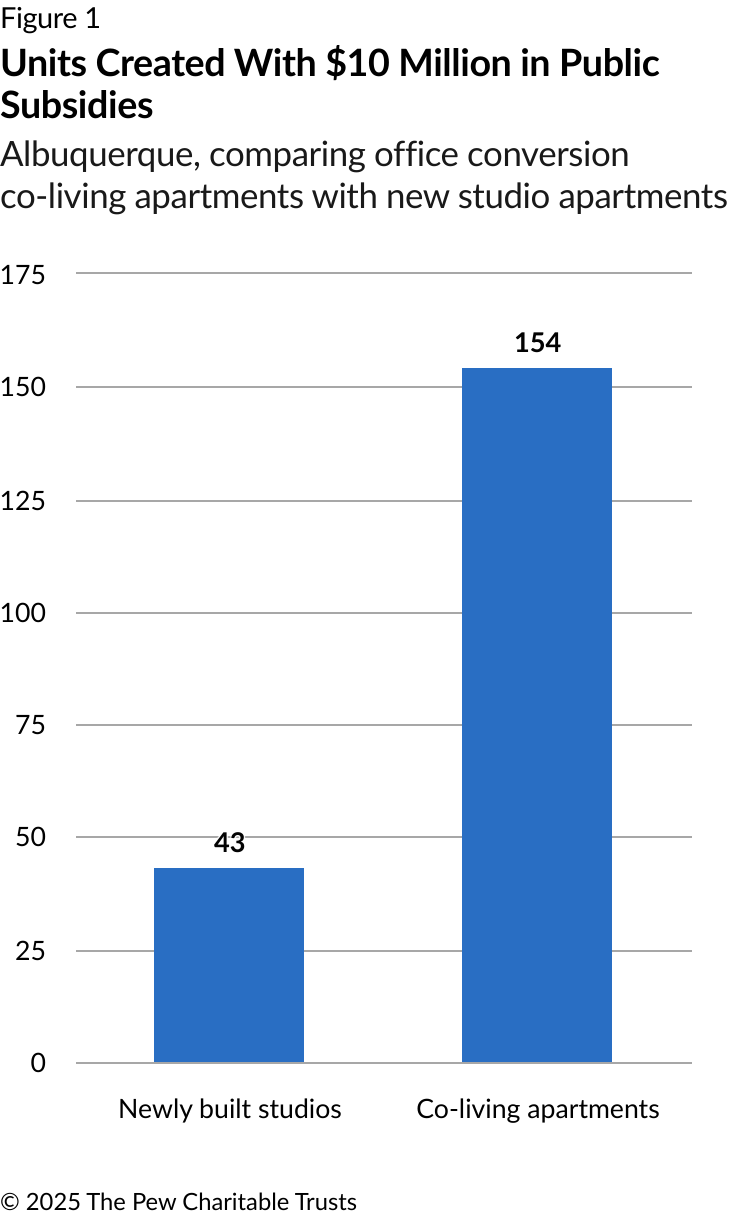

Prior research in other cities from Pew and Gensler has similarly found that directing public subsidies to dorm-style office conversions can produce far more housing than subsidizing the construction of traditional apartments, allowing public money to stretch much further. In Albuquerque, a $10 million subsidy would produce about 154 co-living microapartments, compared with just 43 studio apartments. (See Figure 1.)

These new microapartments would not be aimed primarily at individuals who are experiencing homelessness, but they would help address this problem as well. High housing costs are the primary driver of homelessness; by adding a less-expensive rung on the housing ladder, office conversions would enable more people to find homes they can afford and prevent others from losing their homes.

Removing Regulatory Barriers to Housing Has Improved Affordability Elsewhere

Office conversions and new co-living construction will not erase New Mexico’s housing deficit. But as this Pew/Gensler research demonstrates, they could be a cost-effective way to make a dent in this problem, producing hundreds of microapartments that are affordable to low- and moderate-income residents. That is crucial, because New Mexico’s shortage of homes is taking a toll on its residents by pushing up rents, keeping homeownership out of reach, and fueling homelessness.

Other cities and states have successfully reversed those trends by removing regulatory barriers to housing—for example, by easing land-use rules, simplifying permitting, and modernizing building codes. Even as housing costs and homelessness have soared in New Mexico, rent growth has slowed and homelessness has declined in cities that have added large amounts of housing, such as Austin, Texas; Houston; Minneapolis; and Raleigh, North Carolina. States such as Arizona, Colorado, Montana, Washington, and Texas have also enacted similar laws, making it easier to build new housing.

Their playbooks are available to Albuquerque and Santa Fe—and to New Mexico at the state level. But, in addition to modernizing regulations, New Mexico and its cities could improve affordability and reduce homelessness by adding dorm-style housing, either as a second life for vacant offices or through new construction near commercial areas.

Alex Horowitz is a project director and Tushar Kansal is a senior officer with The Pew Charitable Trusts’ housing policy initiative.