Interest Surging in Nondegree Credentials but How Do Students Finance Them?

Survey shows that many pay out of pocket for what can be costly vocational certificates and professional licenses

Interest in nondegree credentials (NDCs), such as vocational certificates and professional licenses, has grown significantly in the United States in recent years, but information about how people are paying for these programs has been scarce—until now. Recent survey data shows that more than half of these students report that they cover the costs out of pocket—a concerning trend, given that many of these programs come with a hefty price tag.

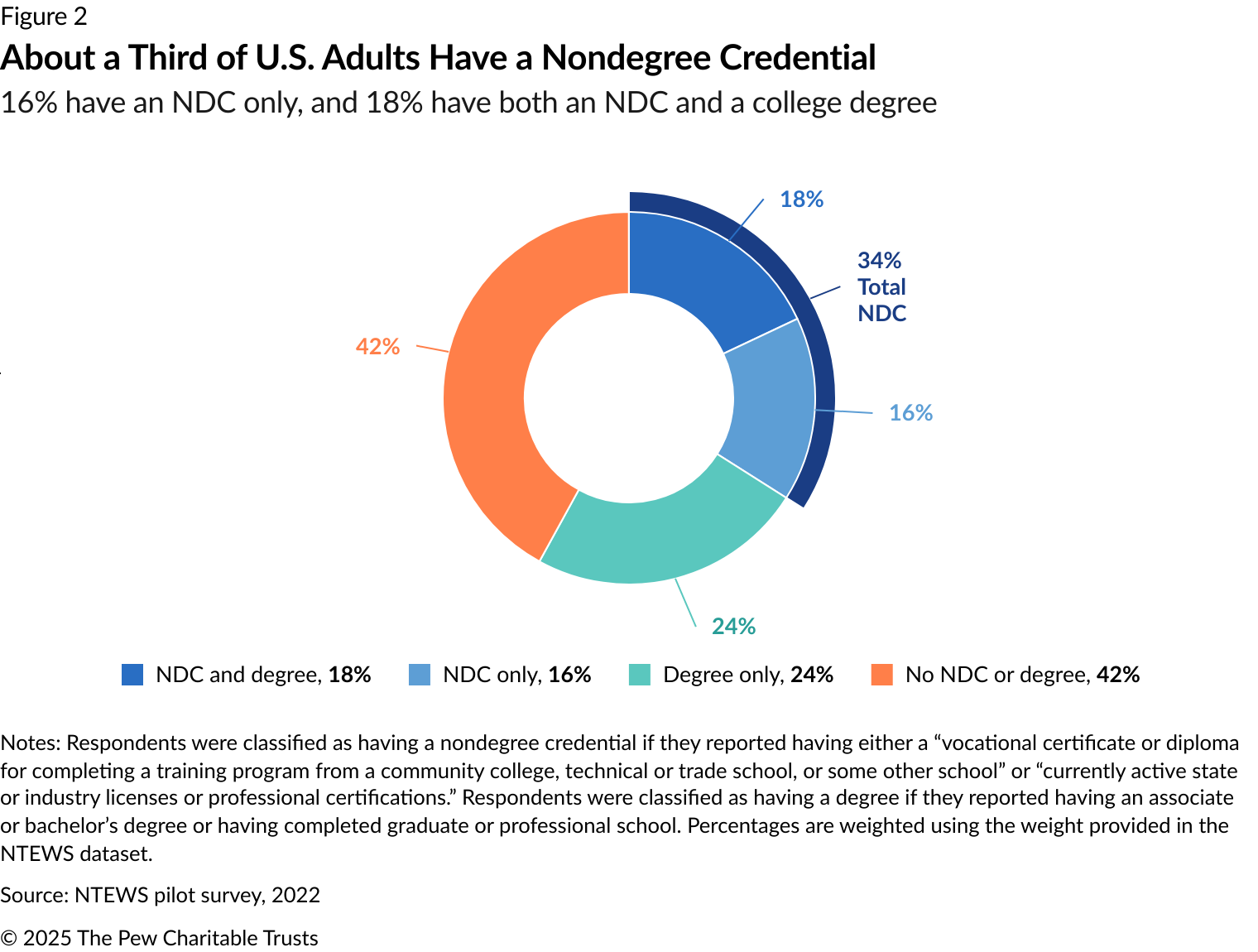

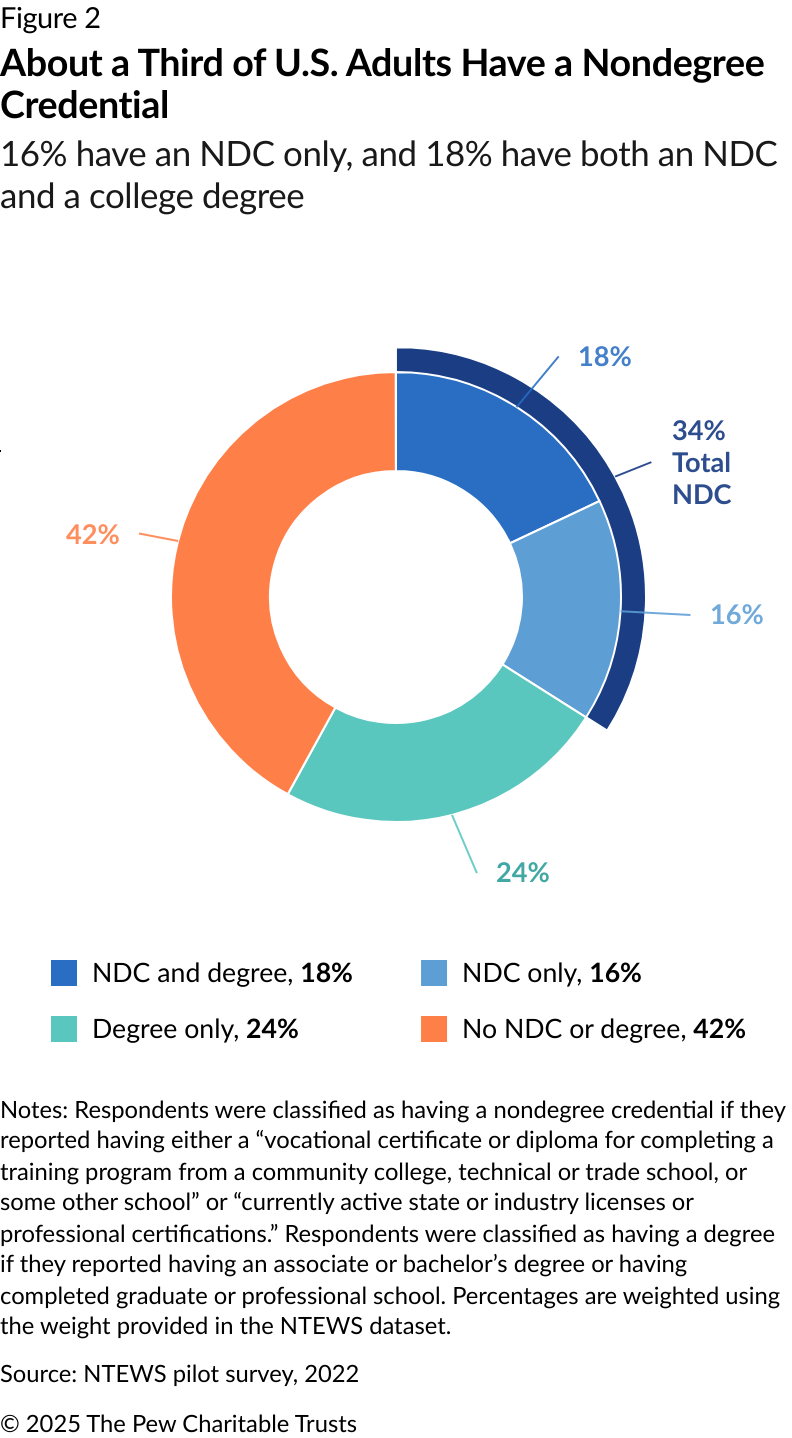

About a third (34%) of U.S. adults have completed such a credential program, according to new government data analyzed by The Pew Charitable Trusts. In fact, the annual rates at which people recalled attaining their NDCs as much as tripled from 2009 to 2021. Findings from the 2022 pilot data from the National Training, Education, and Workforce Survey (NTEWS)—a nationally representative survey of over 15,000 respondents fielded by the U.S. Census Bureau—shed light on how students are managing the costs associated with these credentials.

Although no industry standard definition exists for NDCs, they are different from traditional degree programs, such as associate or bachelor’s degrees, in several ways. Programs to earn NDCs are typically much shorter in duration than degree programs—ranging from a few weeks to less than a year—and they are offered by both accredited schools and unaccredited schools as well as businesses, associations, and government agencies. In addition, these credentials can expire, unlike degrees, and may not always be renewed. The programs are usually designed to train students in a specific skill or industry–such as welding, construction, dental assisting, or web programming–rather than encompassing a core curriculum or broader field of study. They go by different names, including certifications, licensing, boot camps, micro-credentials, and even apprenticeships.

And how students pay for NDCs is a key policy issue. Research indicates that the cost of the programs can vary widely. One 2024 study found that the median monthly cost of attendance for NDCs across an academic year, including living expenses, was $2,112 or $2,552, depending on the type of provider. These programs often don’t qualify for federal aid, such as Pell Grants or student loans, because they are too short in duration to qualify for the federal aid program under Title IV, are offered by unaccredited providers, or are designated as noncredit programs within accredited institutions. However, Congress recently passed legislation that includes provisions that expand Pell eligibility to shorter accredited programs.

This analysis focuses on two types of credentials: respondents’ most recent vocational certificate and most important currently active license or certification. Although there are different definitions of what constitutes an NDC, NTEWS defines a vocational certificate as “a vocational certificate or diploma for completing a training program from a community college, technical or trade school, or some other school” and excludes associate degrees. Professional licenses are defined as “any currently active state or industry licenses or professional certifications,” including “teaching license, land surveyor license, nurse midwife certification, Cisco Certified Network Associate (CCNA), etc.” and exclude “vendor’s licenses or other licenses to operate a business.”

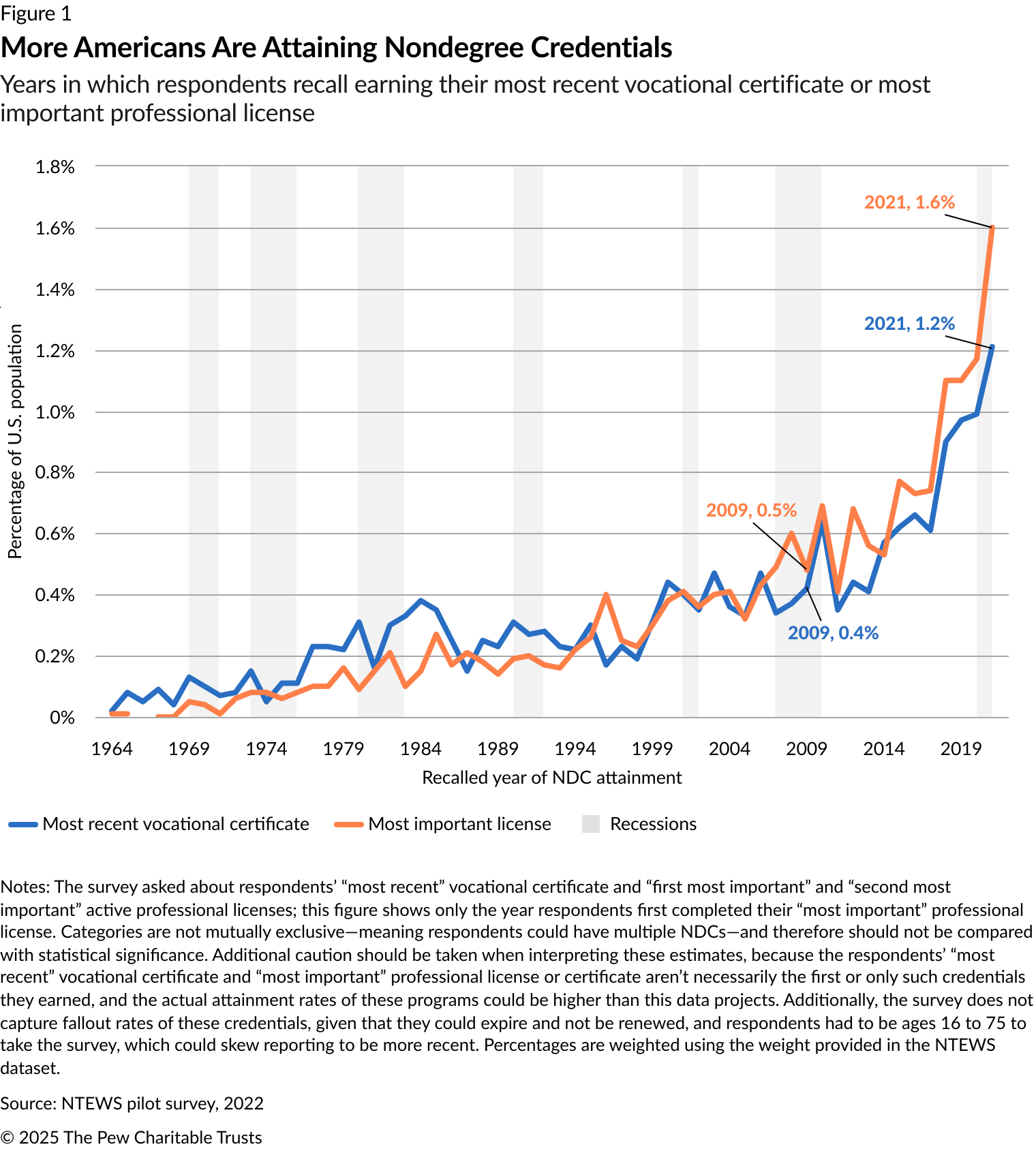

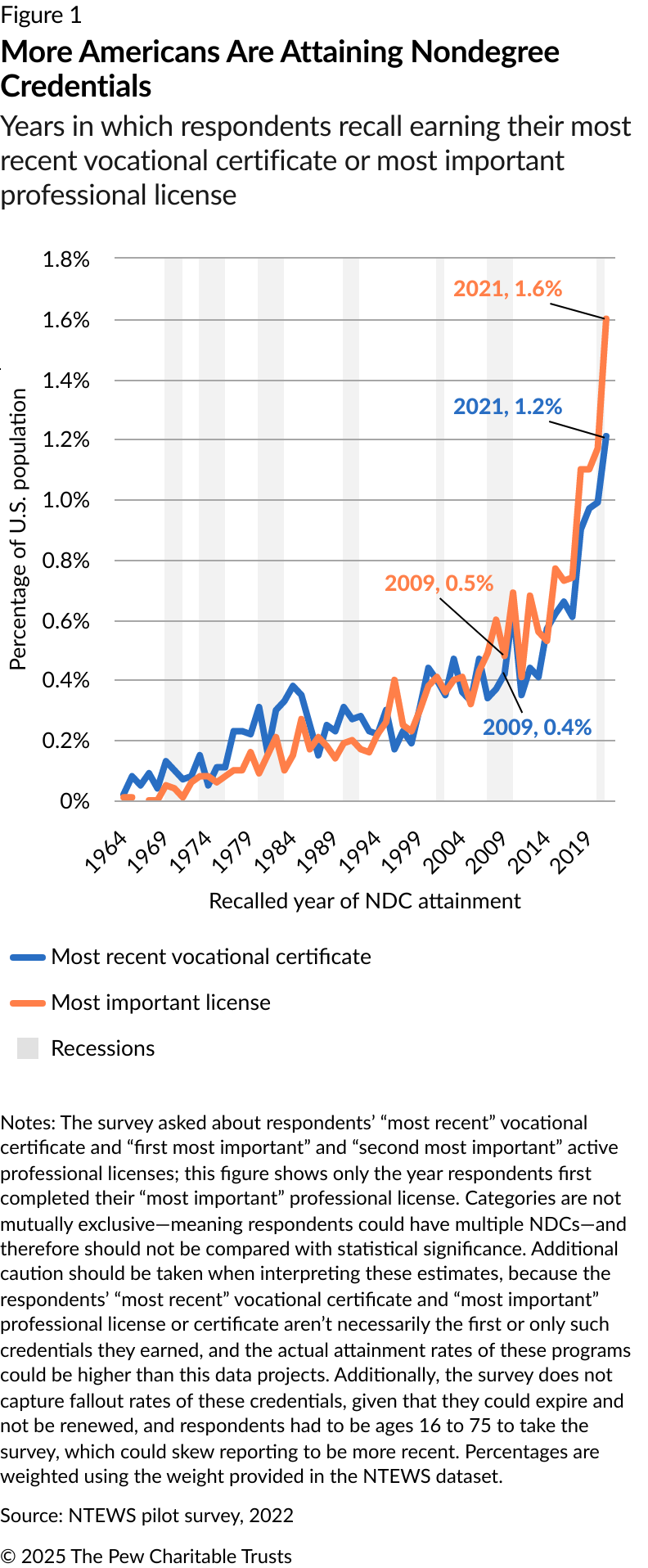

NDCs have surged in popularity and are often pursued in addition to a degree

To gauge the rapid growth of NDCs from 2009 to 2021, the survey asked respondents to recall the year they attained their most recent vocational certificate and their most important professional license. The results indicate that annual vocational certificate attainment increased from approximately 0.4% of the U.S. adult population in 2009 to as high as 1.2% in 2021, and professional license attainment from about 0.5% to as high as 1.6% over the same period. (See Figure 1.) This growth stands in stark contrast to waning enrollments in undergraduate degree programs. As of the spring of 2025, bachelor’s degree enrollments were down 1.1% since the spring of 2020, and associate degree enrollments were down 7.8%.

Several factors could be driving the popularity of NDCs. Because the programs are shorter in duration, NDCs offer a flexible way for workers to gain more advanced skills, pivot into a new role, or acquire professional credentials without a degree. Employers may value this flexibility, as it helps workers adapt to changing labor market needs. Studies have also documented the importance, and proliferation, of these credentials as a revenue source for professional associations, state governments, and colleges and universities.

The credentials are often earned in addition to a degree or a separate NDC. The survey found that among all holders of NDCs (34% of U.S. adults), about half have no degree (16%), and a similar share (18%) do have one. (See Figure 2.) The survey did not measure whether respondents who held both credentials earned their NDC before, after, or during attainment of their degree. More detail on these distinctions should be a subject for future research.

Most students pay out of pocket for NDCs, but data gaps remain

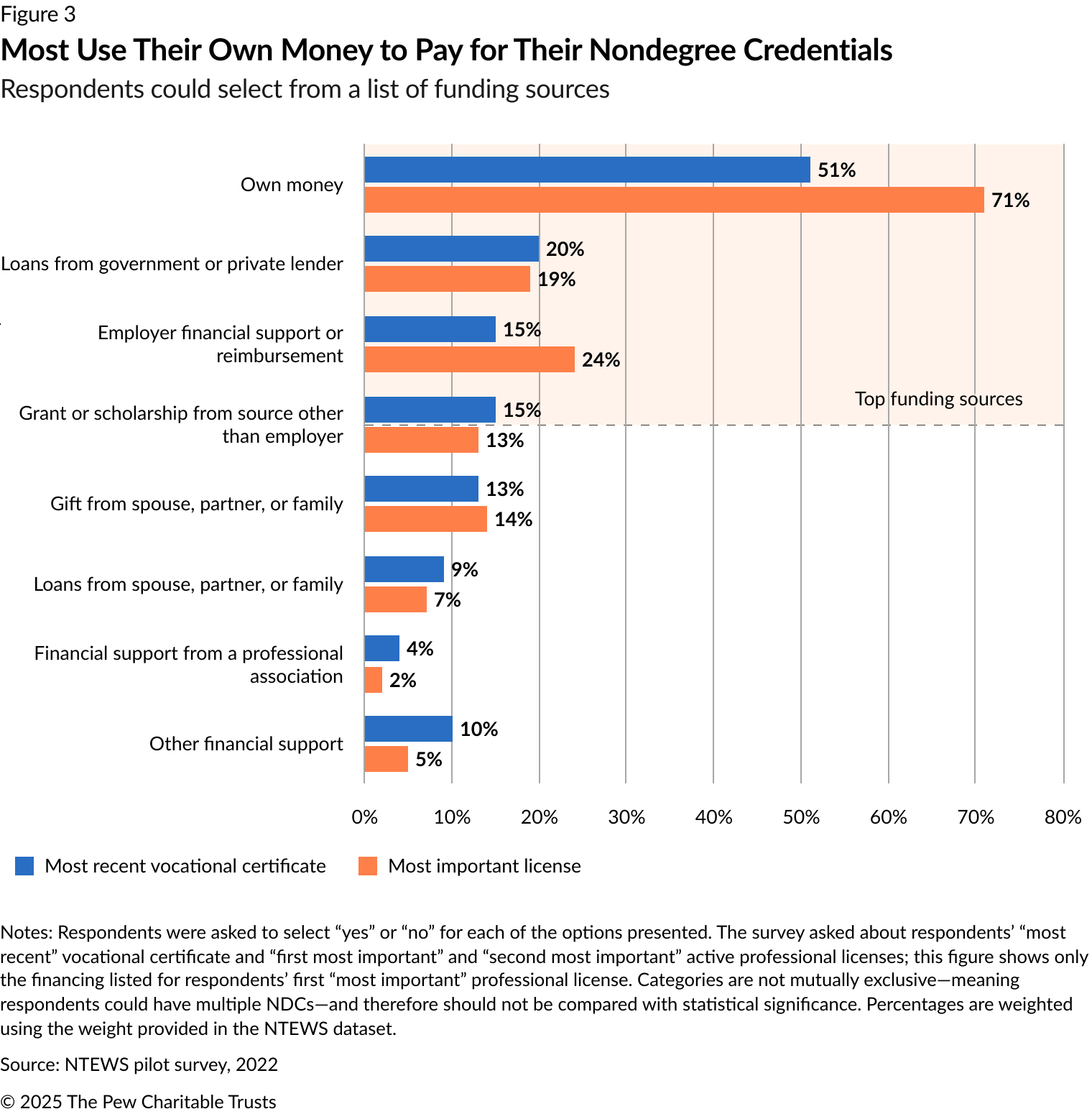

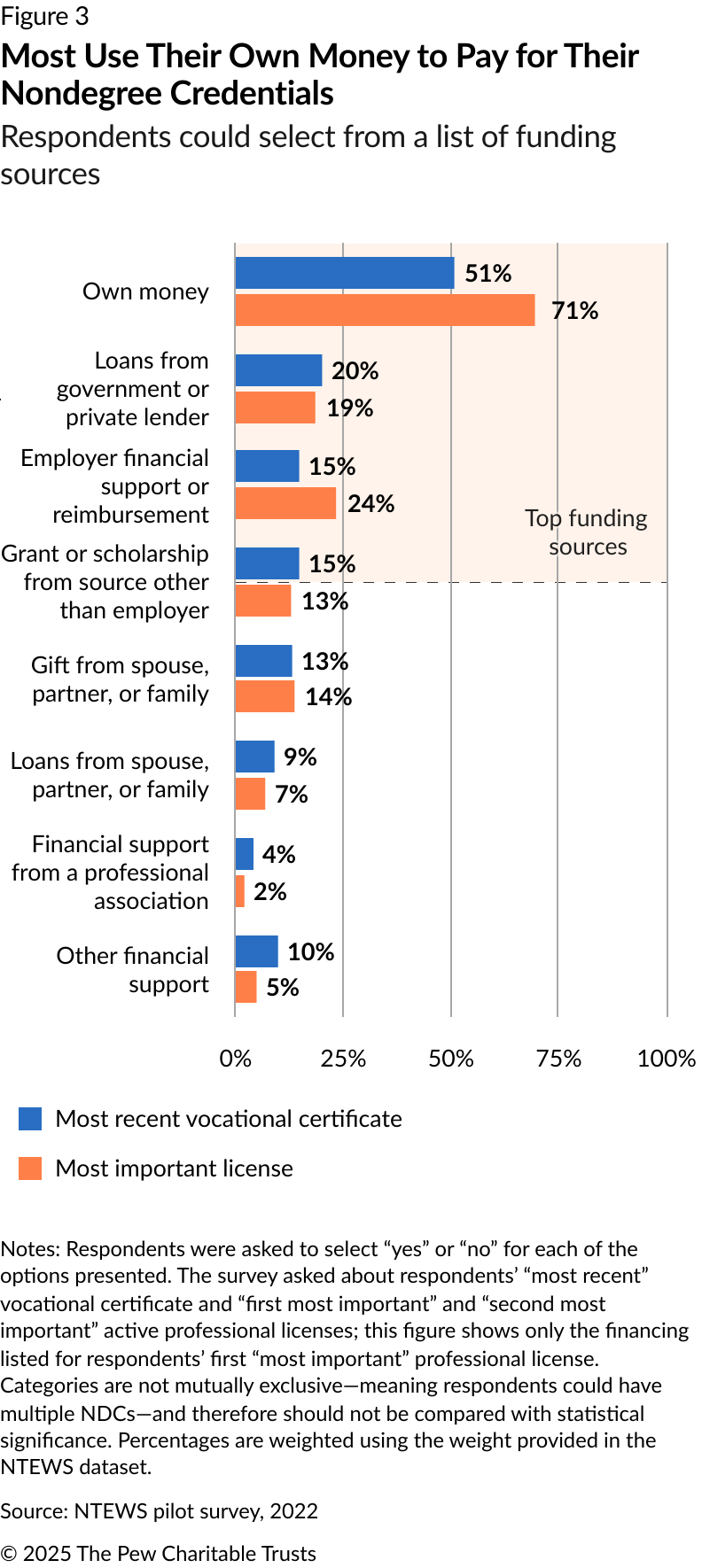

To date, there has been little research on how students pay for NDCs, but this survey provides new insight. Respondents were asked to select from a list which financing options they used to pay for their NDCs; they could choose more than one. Most said they used their own money (51% for their most recent vocational certificates and 71% for their most important professional licenses). About a fifth cited government or private loans (20% and 19%, respectively). Meanwhile, 15% mentioned employer financial support for their most recent vocational certificate, and 24% listed this form of financing for their most important professional license. For vocational certificates, 15% used grants or scholarships from sources other than their employer. Most respondents (66% for their most recent vocational certificates and 63% for their most important professional licenses) selected only one form of financing for their NDCs. (See Figure 3.)

It is concerning that most students pay out of pocket for their sometimes-costly NDCs, especially because one study found that over half of these programs’ hourly costs exceeded minimum wages across 15 states. At the same time, state investment in these programs has increased significantly, with 32 states committing $5.6 billion in 2024 to short-term credential initiatives—an almost $1.8 billion increase over the previous year. Understanding which programs offer the best cost benefits for students and evaluating any trickle-down effects of the investments on the cost of attendance could help states ensure that their funds are used effectively.

Although this data sheds light on how students pay for NDC programs, it is incomplete. Understanding how students pay for the full range of costs—tuition, fees, supplies, and living expenses—could help policymakers understand the extent to which people are facing risky financial choices. For example, it is not clear how many NDC students rely on credit cards, which higher education research finds can lead to high interest rates and ongoing financial stress when students are unable to pay off their entire credit card balance each month.

The extent to which income-sharing agreements (ISAs) are used to pay for NDCs is also unclear from this survey. These agreements between students and their programs typically allow the latter to cover the cost in exchange for a portion of salary after graduation over a set period or until the program’s costs have been covered. Students’ experiences using these forms of financing are understudied, but an evaluation of four ISA programs showed varied results. This study found that while students generally preferred ISAs to traditional loans, many found the repayment terms confusing and struggled to stay current with payments. Only 41% said the program was worth the cost.

Lastly, the NTEWS survey doesn’t measure respondents’ use of Post-9/11 GI Bill benefits from the Department of Veterans Affairs, a robust program that former service members can either use for themselves or transfer to family members for educational and housing expenses. Notably, those benefits are not limited to accredited programs. The Department of Veterans Affairs estimates that 49% of eligible schools don’t have a federally assigned identifying number, such as an IPED or OPE ID, which means that they are ineligible to receive federal financial aid. And previous Pew research found that about 1 in 4 undergraduate student veterans took out student loans even though they had access to these benefits. More research is needed to understand the extent to which Post-9/11 GI Bill dollars are financing NDCs, the quality of these programs, and the prevalence of borrowing among NDC veteran students.

NDCs are a rapidly growing and complex yet unexplored component of postsecondary education and training. As these programs continue to proliferate, policymakers and the public would benefit from data that provides a deeper understanding of how students pay for them. More data also would provide needed insights into students’ experiences with these programs, and how these factors may vary across different populations, industries, and states.

This article is the first in a series that will report on findings from the 2022 National Training, Education, and Workforce Survey (NTEWS) pilot, a nationally representative survey of 15,734 respondents ages 16 to 75. The survey was sponsored by the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES) within the National Science Foundation and the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) and was administered by the U.S. Census Bureau. NCSES designates the NTEWS pilot as an experimental statistical product, produced to benefit users in the absence of other relevant information and to improve future iterations of data collection. This product may not meet some of NCES’ quality standards. The findings from this analysis should not be used to make official statements or inferences about characteristics of the population or economy. This survey is the only nationally representative data source for many key indicators of credential attainment. The dataset was downloaded from the NCES website on Feb. 2, 2025, and can be accessed here.

Ilan Levine works on The Pew Charitable Trusts’ student loan initiative.