Massachusetts Harnesses Data from Multiple Agencies to Improve Public Health

Lessons learned can help other states overcome barriers that prevent collaboration

Editor’s note: This article was updated on July 18, 2025, to correct Dr. Monica Bharel’s title.

Overview

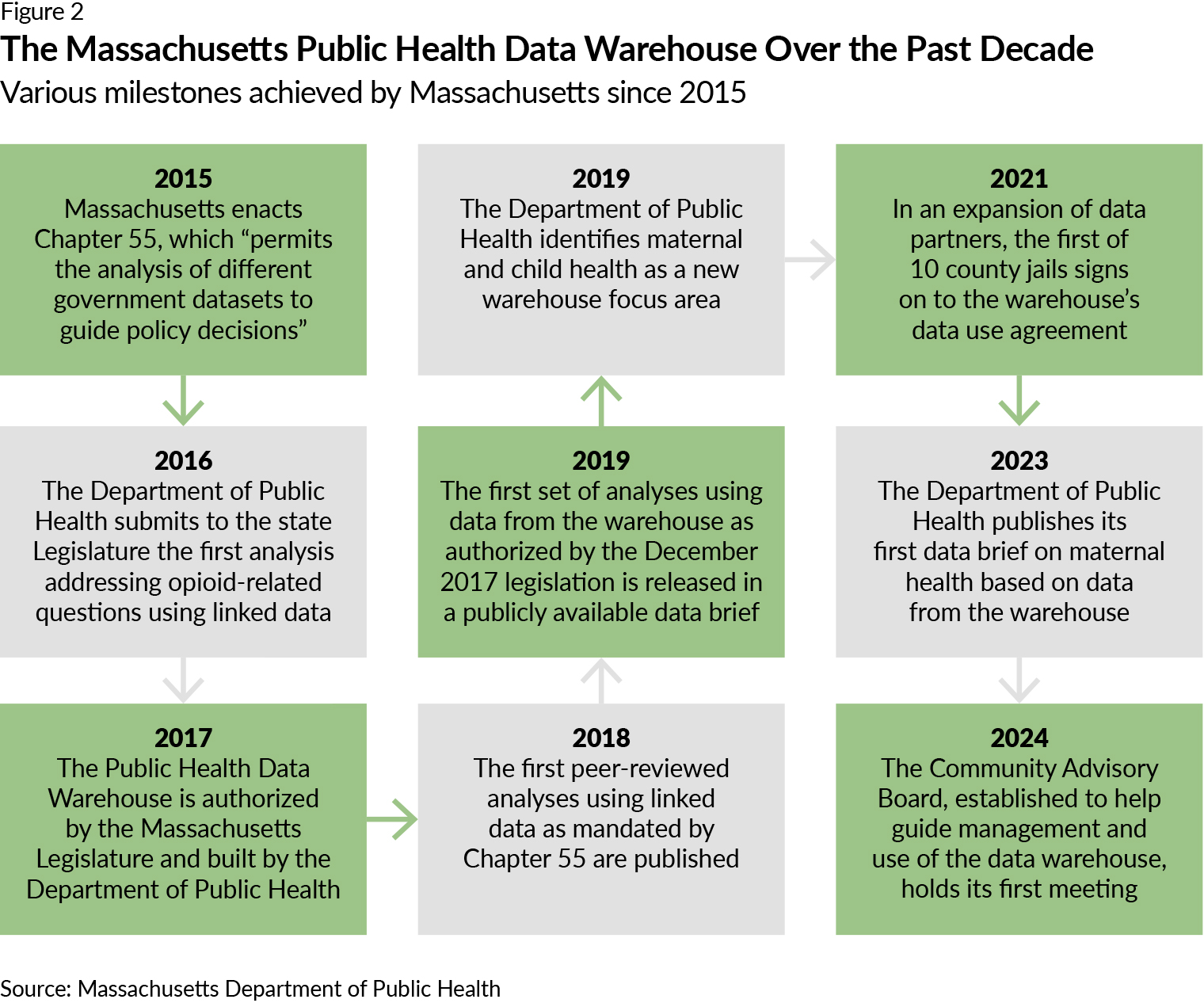

In Massachusetts, data from 2013 and 2014 revealed that when people are released from prison, their risk of dying from an opioid-related overdose is more than 50 times higher than that of the general public.1 State public health leadership sought to develop a more complete understanding of the factors contributing to the opioid epidemic beginning in 2015 by synthesizing data from a variety of sources, including hospitals, prisons, and social services agencies. Then, in 2019, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (DPH), as mandated by the state Legislature, collaborated with county jails throughout the state to use that data to design and implement a pilot program in seven facilities for individuals to receive medications for opioid use disorder. The program reduced mortality from all causes among this population by more than half compared with a control group following release from incarceration; findings also revealed that participants were less likely to experience an opioid-related overdose. This is one example of what the state has been able to achieve with its Public Health Data Warehouse, which brings together data from across government agencies to identify trends and focus resources for pressing public health issues.

In 2015, before the warehouse launched, interested parties such as health care providers, public health scientists, corrections officials, social workers, insurers, and others could analyze their own opioid-related data, but they could not easily share and compare information with each other. They could see only their own piece of the puzzle. The warehouse has enabled policymakers to see a much more complete picture of opioid-related impacts within the state and allowed interested parties to collaborate on more effective, systemic solutions. Following its early success in reducing opioid-related mortality, DPH continued to expand warehouse use to address other aspects of substance use disorder as well as maternal and child health, COVID-19, illnesses and deaths related to climate change, and racial and health inequities.

This issue brief is the first in a collection of publications that examine promising data sharing practices involving public health. It is a resource for state and local health officials seeking new ways to make better use of available data to improve their communities’ health. These insights can help officials in other jurisdictions build and strengthen their data sharing infrastructure to foster more collaboration between health departments, health care providers, social services agencies, and other public and private institutions. This better-informed collaboration will support more effective, evidence-based solutions for public health concerns.

Key takeaways from Massachusetts’ experience offer several suggestions such as:

- Engage executive leadership for support.

- Show value and build trust quickly.

- Build flexibility into the data system and its funding.

- Involve a range of internal and external partners.

The information included here is based on interviews that The Pew Charitable Trusts conducted from September to November 2024 with six current and former Massachusetts officials involved in designing and implementing the data warehouse, including former public health leadership, current public health staff, a partner with another state agency, and a member of the state Legislature.

The promise of linking cross-sector data

Health, housing, family services, and other public agencies have large, complementary datasets that, if shared and linked together, have the potential to improve each other’s work by providing deeper insights into health-related risk factors—but structural, legal, and technological barriers often prevent that from happening. So, DPH worked with the state Legislature to develop and enact a bipartisan statute that requires multiple government agencies to share relevant data with the state public health department via its Public Health Data Warehouse. State and local health departments, colleges and universities, health care providers, foundations, private companies, think tanks, and other partners can all apply to use the warehouse to analyze and address priority health and quality-of-life issues affecting the people of Massachusetts.

In building the warehouse—designed to meet ever-changing public health priorities—Massachusetts created a data sharing infrastructure that helps to facilitate measurable improvements to health outcomes.

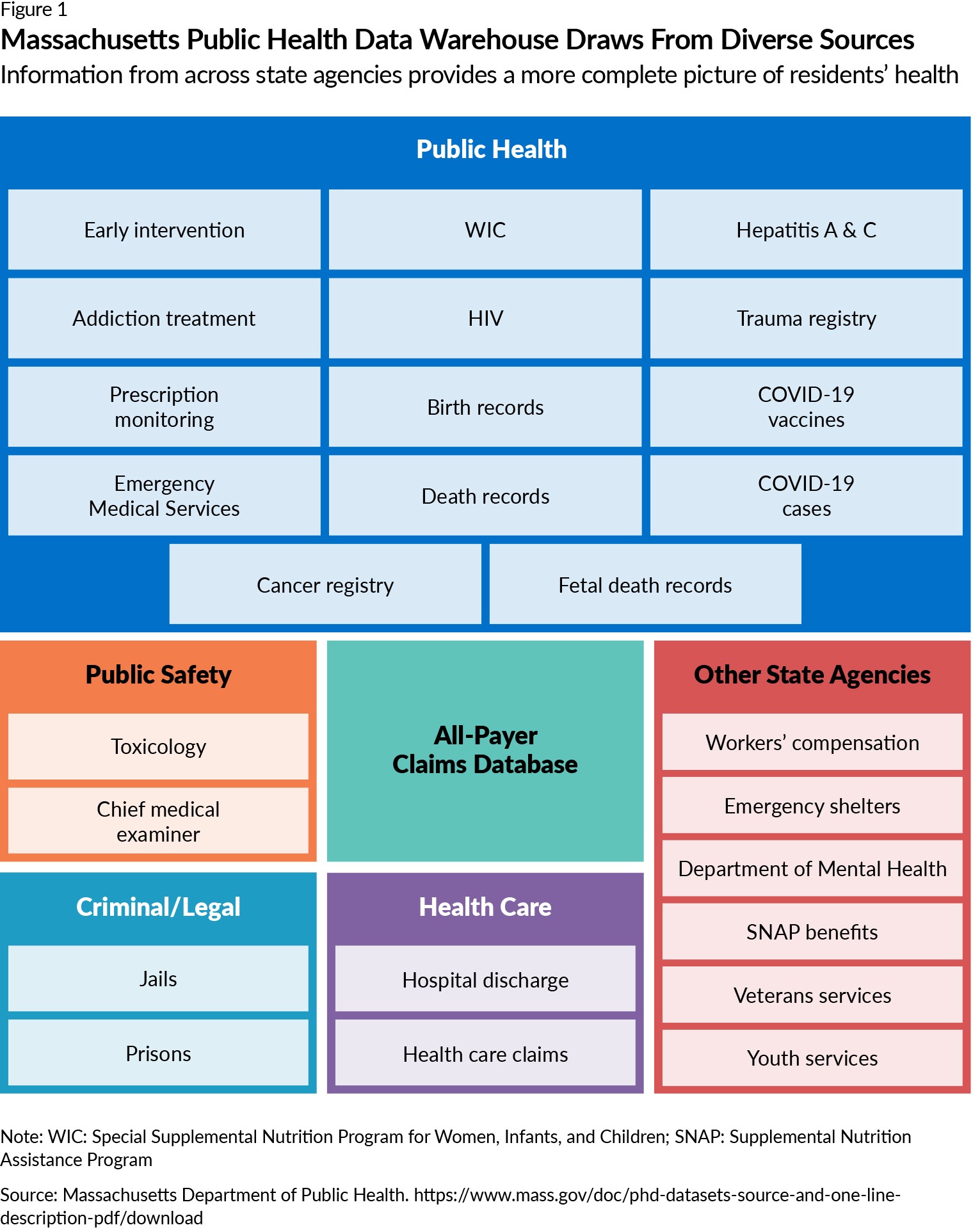

Individual databases tend to have missing information. By linking data from multiple overlapping sources (see Figure 1), the warehouse has been able to fill in many of the gaps; it now holds more than 6 billion data records representing Massachusetts residents. By better leveraging existing data sources, the warehouse enables its users to more precisely identify populations in which inequities are present (such as those with disabilities and those experiencing homelessness), allocate resources to those communities, and work to narrow health disparities.

However, public health officials also recognize that a small proportion of state residents are still not represented in the warehouse and are likely among the most marginalized communities, such as people who lack access to health insurance and housing. Officials continue to fill in some of these data gaps in the hope that they can decrease the existing margins and better focus resources on those people who may benefit the most.

One major success of the warehouse: DPH has improved its understanding of health issues facing the state’s population. For example, as noted earlier, it found that there was a very high risk of overdose death immediately upon a person’s release from incarceration. Among high-risk populations, people using medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) had a reduced risk of overdose death and all-cause mortality. Based on data from the warehouse, Massachusetts enacted and DPH implemented a pilot MOUD program within seven county jails that produced several positive outcomes, including a 50% reduction in mortality from all causes.

By bringing together data sources within the warehouse, DPH also has a better understanding of other health concerns affecting the state. For example, by combining data from the Department of Industrial Accidents and DPH’s Registry of Vital Records and Statistics, public health officials found links between work-related injuries and opioid-related overdose deaths.2 And by examining data from Vital Records and the Center for Health Information and Analysis, officials determined that individuals with disabilities were at heightened risk of severe maternal morbidity.3

Lessons learned

Massachusetts DPH’s experience designing and implementing the warehouse can offer other states guidance as they look for opportunities to break down the barriers that keep agencies from collaborating to improve public health.

Produce actionable information and positive results quickly

The officials whom Pew interviewed stressed the importance of delivering meaningful, measurable results soon after the warehouse was established to quickly demonstrate value and build trust among both policymakers and data partners.

By focusing first on the opioid epidemic—a priority for the governor, Legislature, and residents of Massachusetts—the warehouse quickly yielded actionable information on at-risk populations such as those exiting incarceration and potential intervention points to reduce health disparities.

This initial success attracted a wider range of state agencies with additional health priorities to participate in the warehouse, creating a cycle of data sharing, analysis, use, and positive outcomes. (See the timeline in Figure 2.) It also generated interest from other states hoping to learn about the approach that Massachusetts had taken to cross-sector data sharing.

To promote the work of the warehouse and its positive results, officials described briefing state leadership directly, publishing peer-reviewed articles, and using other tools, such as press releases and data briefs. These actions generated executive-level support, which allowed the warehouse to “[cross] over administrations” and changes in statewide leadership, said Dana Bernson, director of the Data Science, Research, and Epidemiology Division in the Office of Population Health at DPH, which oversees the warehouse. Bernson also noted that this support from both the governor and commissioner of public health was crucial in helping the warehouse become what it is today.

Design a flexible system to address an expanding range of health issues

State officials said that experimenting with the warehouse and making improvements as they learned from their mistakes proved better than aiming for perfection from the onset. As a 2020 publication in the New England Journal of Medicine Catalyst notes, DPH intended to create a data sharing system that is both flexible and responsive to the evolving public health needs of the state, using a legal framework and technical structure that could be adapted as needed. The department used this approach to intentionally expand the warehouse beyond opioid use to include various new datasets, data partners, and public health priorities.

Given Massachusetts’ experience, states exploring public health data sharing projects should:

Add data sources to build a better understanding of health issues

Former Commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health Dr. Monica Bharel described the importance of “direct and frequent” engagement with peers at other state agencies to discuss the potential inclusion of their datasets and grant assurances that the warehouse was stable and secure. By championing a tool that she saw as vital to advancing health equity within the state, Bharel was able to secure numerous data sharing commitments. This enabled Massachusetts to successfully link data in the warehouse from various bureaus within DPH, as well as other data from corrections, housing, veterans services, and mental health agencies, to better focus health programs and funding.

Determine where data use agreements can be refined over time

The department’s multiparty data use agreement (DUA), which is a legal contract between a data owner and the parties that will be using the data, evolved to match the growth of DPH’s work and the expansion of the statutory authority. Department officials said that the agreements were rigid in the early days of the warehouse; for example, any changes to a dataset meant that all parties had to re-sign the DUA. Now that DPH has further established the necessary relationships with data sharing partners, it has been able to provide greater flexibility in the legal structure. Dataset details have been relocated to secondary documents, which only necessitate agreement with the specific data provider and subsequent notice to all other parties. That evolution, officials note, was the right approach. Using more guardrails up front to allow for transparency across all data partners improves consensus building and buy-in for the warehouse.

Build an increasingly strong means for linking data

Because Massachusetts already had an All-Payer Claims Database (APCD), which securely collects health care claims data from almost every health payer within the state, DPH used it as the initial “spine” that supports all the other datasets within the warehouse, covering up to 98% of the population. Housed in the state’s Center for Health Information and Analysis (CHIA), the warehouse can use a base dataset that includes a large percentage of the state’s population, making accurate data analysis much more feasible. Since the warehouse’s inception, CHIA has paired further datasets with the APCD (for example, hospital inpatient, outpatient, and ER data, as well as Medicare data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services) to build an even stronger system, which is integral to matching records from all the various datasets.

Prioritize data privacy

In building the initial warehouse, Bharel said that protecting people’s information was “the number one priority even before quickly addressing the opioid overdose [crisis].” On the expedited, one-year timeline that the legislation necessitated, DPH created a warehouse that protects its sensitive health information via a well-informed design and a flexible DUA.

Almost immediately following passage of the initial legislation, DPH leveraged an already established privacy-related technical approach that CHIA was continuing to refine. This work focused on a master patient index, a database that links records across systems, with CHIA taking a unique approach that protects personally identifiable information. Through a partnership with DPH, CHIA was able to apply this model to the warehouse. Interviewees said that this partnership—with CHIA as an independent third party—bred trust in the data warehouse among state agencies that already understood and trusted the approaches that CHIA took to secure data.

The state worked to build one multiparty DUA from the outset; this agreement guides the work of the warehouse and provides transparency to the participating state agencies, showing that they are all operating under the same rules. The DUA covers the privacy components of the data sharing practices and provides for a data steward to make decisions regarding datasets that have specific federal requirements around sharing, thereby allowing more sensitive datasets to be part of the warehouse while not being accessible across all projects. Though the multiparty DUA required more work in the early stages of this data sharing practice, the assurances it has been able to provide state agencies regarding their data contributions and the transparency of the process itself have been vital, especially in building the relationships and trust that have made the warehouse’s work possible. As Bernson notes, the multiparty DUA has provided a “return on investment … [that] made that up-front work absolutely well worth it.”

Leverage partnerships and creative funding streams

Although the warehouse had bipartisan support, legislators did not appropriate funding for the project. Securing funding via the legislative cycle was not a viable option given the expedited, one-year timeline in the initial legislation and the urgent nature of the opioid crisis itself.

Instead, the Data Science, Research, and Epidemiology Division of DPH taps multiple funding sources to accomplish its work. Early on, division staff recognized the value of forging partnerships with entities outside of the department for both establishing the warehouse and helping to address the legislative mandate’s reporting requirements. In addition to helping DPH to keep data secure, CHIA guided the warehouse’s development of data-matching processes (a practice that compares data from multiple sources to determine which data refers to the same person), which helped DPH avoid the time-consuming and costly process of building the warehouse from scratch.

Though limited staffing capacity may often hinder a department’s ability to conduct large-scale data analyses, DPH’s model of working with external collaborators helped to bypass this issue. Academic institutions, health care delivery systems, and other entities may apply to work on analyses using data from the warehouse with the prerequisite that these projects align with the department’s priorities. A benefit to those partnering with DPH is the opportunity to author peer-reviewed publications based on analyses performed to address public health priorities of the department, so long as someone from the department is involved with both the writing and analysis.

DPH continues to be creative in braiding federal and state funding. Some funding has been provided through federal grants already allocated to DPH on topic-specific work that the warehouse is able to support, while other federal funds such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Public Health Infrastructure Grant also provided assistance. Although this piecemeal model makes the most of available funding, it leaves these efforts vulnerable to being cut should funding priorities shift in the coming years.

DPH requests that groups with grant funding for analyses support the warehouse through data management and administration fees, providing another source of funding. Additionally, as other Massachusetts offices and agencies apply to use data from the warehouse to assess and demonstrate the effectiveness of their own programs, they will hopefully be able to offer programmatic and financial support to help sustain the data sharing practice.

Implement effective processes for collaboration

State officials said that a lack of cohesion between various departments across DPH is a barrier to data sharing that they have previously experienced. Fortunately, Massachusetts officials who developed the warehouse knew of this challenge from the onset and intentionally engaged data, IT, and legal representation from their agency and other state agencies to ensure that, as Bernson notes, they were “always in the room at the same time” to think through problems and make decisions together. By crafting a model that generated buy-in early on from groups that often have differing priorities, its leadership has helped the warehouse to remain sustainable and advocates for similar models of collaboration elsewhere.

Those interviewed attribute the warehouse’s success in large part to treating these partners as the experts that they are, rather than just sources of data. DPH staff working on the warehouse actively involve the data partners in conversations regarding analyses and the requests for data use. This shared decision-making approach to communication with the various bureaus and departments has helped to build the cohesion and trust necessary for effective implementation.

Likewise, state officials also said that it is critical to have early collaboration with community members, especially those in various priority populations, as part of building a data sharing practice—and noted this as an area where they should have done better work as the warehouse was initially constructed. However, DPH established the Community Advisory Board in early 2024 as a mechanism for key community stakeholders to weigh in on public health priorities and plan how best to disseminate findings from the warehouse to the general public in a digestible, useful format.

Promising practices for all states

- Engage executive leadership for support. Provide leadership with a compelling case for what a data sharing system can help to achieve and engage them in promoting the model among legislative partners and working through structural barriers.

- Show value and build trust quickly. Identify pressing public health concerns that have the attention of departmental and/or state leadership; this can be especially helpful in garnering an executive champion. Focus on areas where the system can prove its value early and use that to generate further interest and build confidence in the work. This is especially helpful for legislators who need to show results in limited time windows.

- Build flexibility into the data system and its funding. Work to creatively combine funding streams to provide support. Don’t get stuck on building a perfect practice up front; rather, focus on having components in place that can adapt over time as lessons are learned and public health priorities shift, such as flexible data use agreements and data structures.

- Involve a range of internal and external partners. Focus collaboration on generating buy-in for participation from potential data partners and establishing cross-agency trust. Embrace shared decision-making with IT and legal staff from the onset.

Conclusion

Massachusetts’ Public Health Data Warehouse quickly and effectively brought together disparate data sources to better understand and address health issues within the state. Identifying a pressing use case—in this case, the opioid epidemic—allowed the state to garner executive-level support and generate momentum for the practice. This model demonstrates that, even without dedicated funding, building a sustainable data sharing practice is feasible through an approach centered on flexibility and engagement with a multitude of partners. Other states can look to lessons learned by Massachusetts as they build their own data sharing practices to address pressing public health issues.

Acknowledgements

This brief was researched and written by Pew staff members Ian Leavitt, Josh Wenderoff, and Margaret Arnesen. Thanks also to Pew staff members Kimberly Burge, Demetra Aposporos, John Murphree, Carol Hutchinson, Abi Ingoglia, Sara Miller, Heather Cable, and Kathy Talkington for their contributions. The project team would like to thank the state officials who participated in the interviews informing this brief. Also, thank you to our external collaborators, including the Population Health Innovation Lab at the Public Health Institute (Seun Aluko, Beverly Bruno, Stephanie Bultema, Katie Christian, Sue Grinnell, April Aihan Phan, Kendra Piper, Esmeralda Salas, and Rebecca Williams), which conducted and analyzed all interviews, and Amy Killelea, who helped with conceptualization of our guiding research questions. Many thanks to our external reviewers for their support in reviewing this piece prior to publication, including Katie Greene and Joe Gibson. Although they have reviewed the report, neither they nor their organizations necessarily endorse its findings or conclusions.

Endnotes

- An Assessment of Opioid-Related Deaths in Massachusetts (2013-2014), Massachusetts Department of Public Health (2016), https://www.mass.gov/doc/chapter-55-2016-legislative-report-0/download, analysis #4.

- Massachusetts Department of Public Health, “Opioid Overdose Deaths More Likely Among Massachusetts Residents Injured at Work, New Department of Public Health Report Finds,” news release, May 23, 2024, https://www.mass.gov/news/opioid-overdose-deaths-more-likely-among-massachusetts-residents-injured-at-work-new-department-of-public-health-report-finds.

- Massachusetts Department of Public Health, “An Assessment of Severe Maternal Morbidity in Massachusetts: 2011-2022” (2024), https://www.mass.gov/doc/an-assessment-of-severe-maternal-morbidity-in-massachusetts-2011-2022/download.