Most States’ Tax Revenue Falls Below Long-Term Trends Amid Federal Uncertainties

After two consecutive fiscal years of widespread tax revenue declines, states had fewer resources to work with at the start of calendar year 2025 than they had in recent years, which limited their capacity to fund tax cuts, expanded public services, recession preparedness, and other priorities. Although revenue conditions appear to be stabilizing after a period of pandemic-induced volatility, collections have remained sluggish, having performed below their long-term trends—nationally and in most states—for five straight quarters. At the same time, growing uncertainty over federal policy changes is exacerbating fiscal risks and complicating budget planning for states.

Nationally, state tax revenue was 3.2% below its 15-year trend by the end of the fourth quarter of calendar 2024, after adjusting for inflation and smoothing for seasonal fluctuations. This marks a sharp contrast from early 2022 when collections were 14.9% above trend—the highest in at least 15 years.

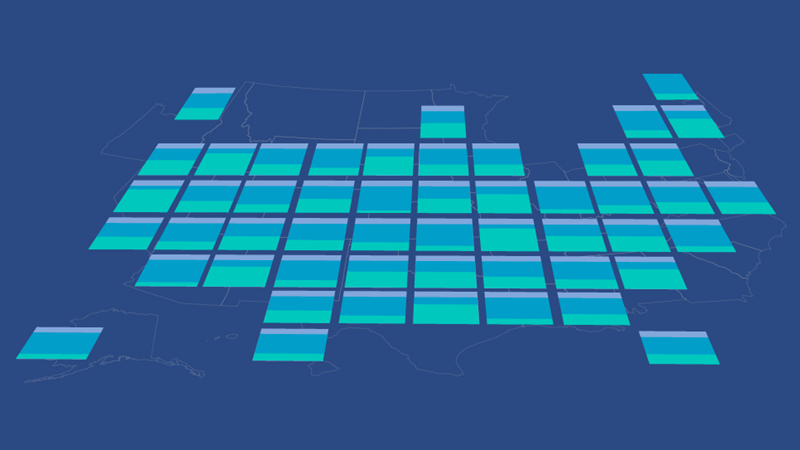

The number of states underperforming their 15-year trajectories has grown steadily over the past two years as collections stagnated after the unexpectedly high levels reached during the second and third budget years of the COVID-19 pandemic. At the end of calendar 2022, only one state had tax revenue below its 15-year trend. But by the end of 2023, that number had jumped to 27, and by the end of 2024, it had reached 40.

Although the scale of these declines resembles past recessions, this slowdown is happening outside of a national recession. Instead, the decreases have been driven largely by the waning of temporary pandemic factors and the implementation of widespread state tax cuts.

But despite underperforming long-term trends, state tax revenue is showing signs of stabilization. Most states experienced more moderate annual declines in fiscal 2024 compared with the year prior, reflecting a return to growth rates more aligned with historical norms after four years of extreme fluctuations. Then, in the third and fourth quarters of 2024, state collections were largely flat.

Fortunately, most states anticipated the decline from pandemic-era highs and were able to maintain relatively strong fiscal positions as they entered 2025. But the continued stagnation is making budgeting more difficult and fiscal commitments—such as broad-based tax cuts and across-the-board wage increases for public employees—made in the previous environment of abundant resources are now posing challenges as revenues flatten. States now face a higher-than-normal risk of structural deficits, where recurring revenue is insufficient to support recurring expenditures.

Recent federal actions are adding to this fiscal uncertainty. During the early months of President Donald Trump’s second term, a wave of executive actions and policy shifts has raised new concerns for state leaders about the stability of their second-largest revenue source: federal funding. Proposed and enacted efforts—such as a sharp rise in tariffs, shifts in immigration policy, large-scale reductions to the federal workforce, and changes to tax policy—could further disrupt state budgets.

Although collections continue to lag long-term trends, state tax revenue has shown some positive signs. Tax revenue rose in half of the states during the first six months of fiscal 2025, an improvement from the same period a year before, when more than four-fifths of states experienced declines. The gains would probably have been stronger and more widespread if not for intentional reductions from newly enacted state tax cuts. Additionally, collections have recently been more closely aligned with states’ annual revenue forecasts than they were amid the volatility of fiscal years 2022 and 2023.

Revenue trends continue to vary widely across the states. During the first half of fiscal 2025, collections ranged from a 10.2% increase in Minnesota and 9.6% increases in Hawaii and Vermont to declines of 19%, 9.4% and 8.4% in Nebraska, North Dakota, and Wyoming, respectively, versus the same period in the prior year.

State highlights

A comparison of tax revenue in the fourth quarter of 2024 versus each state’s 15-year trend levels, adjusted for inflation and seasonality, shows that:

- The states with the weakest tax revenue compared with their long-term trends were Oregon (19.3% below trend), Nebraska (10.5% below), and Iowa (9.2% below). Oregon’s deviation can be explained, in part, by its "kicker” rebate, which returned $5.6 billion in surplus fiscal 2023 funds to taxpayers. Iowa and Nebraska both recently implemented significant tax cuts which lowered collections.

- 10 states bucked the national trend and remained above their 15-year trajectories: Alaska (163.1% above trend), New Mexico (10.6%), Wyoming (5.9%), South Carolina (5%), Vermont (1.3%), Rhode Island (1.2%), Hawaii (0.4%), Nevada (0.2%), Maine (0.1%), and Texas (0.01%). Alaska, New Mexico, and Wyoming benefited from a boost in severance tax revenue related to elevated energy prices and production, though their collections have declined in recent quarters from relatively high baselines.

- The number of states performing below their long-term revenue trends rose from 38 in the second quarter of 2024 to 40 in the fourth quarter of that year, with five states falling below trend during the second quarter (Alabama, Florida, Illinois, Montana, and Nebraska) and three (Hawaii, Maine, and Vermont) climbing back above their long-term trajectories.

Trends by tax type

Nationally, approximately 75% of total state tax revenue comes via levies on personal income, general sales of goods and services, and corporate income. During the fourth quarter of 2024, corporate income taxes outperformed their 15-year growth trends, while general sales taxes and personal income taxes fell short.

- For the 44 states that impose a personal income tax, those collections were 11%, or $15.9 billion, below their 15-year trend as of the fourth quarter of 2024, after adjusting for inflation and seasonality.

- Of the 41 states that collect broad-based personal income taxes:

- 37 had collections that underperformed long-term trends, ranging from 44% below trend in Nebraska and 34.7% below in Oregon to less than 1% below in Louisiana.

- Personal income tax revenue outperformed its long-term trend in Oklahoma (1.2%), Massachusetts (1.0%), Maine (0.9%), and Delaware (0.1%).

- New Hampshire taxes only specific personal dividend and interest income. Tennessee had a tax similar to New Hampshire’s until fiscal 2020, but that tax was fully phased out on Jan. 1, 2021, although the state still reports some lingering collections. In 2021, Washington adopted its own limited tax on capital gains that became effective Jan. 1, 2022. Although the levy is not technically an income tax, the revenue is reported as such to the Census Bureau and so is included in Pew’s counts.

- Of the 41 states that collect broad-based personal income taxes:

- Corporate income tax collections were 8.0%, or $2 .7 billion, above their 15-year trend as of the fourth quarter of 2024. Historically, corporate income taxes are more volatile than other major state taxes. Of the 46 states that impose this tax type:

- 29 had collections that outperformed long-term trends, ranging from 239.8% above trend in Alaska to 3.8% above in Missouri.

- Corporate income tax revenue underperformed its long-term trend in 17 states, ranging from 33.2% below trend in Mississippi and 32.7% below trend in Indiana to 2.5% below in Wisconsin and 1.8% below in Minnesota.

- General sales tax collections were 1.9%, or $2.2 billion, below their 15-year trend as of the fourth quarter of 2024. Of the 45 states that impose this tax type:

- 16 had collections that outperformed long-term trends, ranging from 5.1% above trend in Wyoming to 0.2% above in New York, Utah, and Mississippi.

- General sales tax revenue underperformed its long-term trend in 29 states, ranging from 8.8% below trend in Nevada to 0.2% below in Connecticut.

Recent developments

After peaking in mid-2022, state tax collections have been declining, largely because of the end of the pandemic-era revenue wave and the widespread adoption of tax cuts.

In the fourth quarter of 2024, 27 states reported lower year-over-year inflation-adjusted tax revenue, with decreases ranging from 27.4% in Nebraska to 0.4% in Washington. Yet, even with pervasive declines, states generally experienced less widespread and less severe drops in the final quarter of the calendar year than in the same period a year earlier, which suggests that conditions may be stabilizing.

Furthermore, many states outperformed their revenue forecasts in fiscal 2024. According to the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO), 39 states reported being on track to collect more revenue during fiscal 2024 than they initially projected. States’ fiscal 2024 budgets anticipated a nominal 1.8% annual decline in general fund revenue amid slowing economic growth and waning of temporary factors that drove the fiscal 2021 and 2022 revenue surge, primarily the indirect effects of federal aid to businesses and individuals, a shift in consumer spending patterns, and record-breaking stock market gains.

For the current fiscal year, preliminary data from the Urban Institute shows that total inflation-adjusted tax revenue remains stagnant, even as it continues to surpass expectations. Thirty-four states reported increased nominal collections during the first 10 months of fiscal 2025 compared with the same period a year earlier, which broadly tracks with states’ overall projected 1.9% increase for the year, but that drops to 23 states after accounting for inflation.

Still, after two years of historic growth followed by two years of declines, this stabilization may not necessarily signal improved budget conditions. Although actual collections may be less volatile and align more closely with projections, states will still have fewer resources than they did during the pandemic years even as spending demands continue to grow, meaning budget deficits may become more common.

One key question facing states is whether they can still afford the long-term budgetary commitments they made during the pandemic-era revenue surge—such as tax relief and pay raises for public employees. For instance according to NASBO, fiscal 2023 and 2024 saw the largest net state tax cuts ever recorded (by dollar amount), ranging from targeted, temporary rebates to permanent, broad-based rate reductions. At the same time, lawmakers in 40 states approved across-the-board wage increases of 2% to 12% for state employees in fiscal 2024, up from the 37 states that raised wages in fiscal 2023 and the 25 states that did so in fiscal 2022.

Meanwhile, recent federal policy changes are spurring increasing fiscal uncertainty. Higher tariffs can raise prices and operating costs, discouraging consumer spending and straining businesses, particularly in manufacturing and retail, while shifts in immigration policy may reduce the labor supply for immigrant-dependent sectors like agriculture, construction, and hospitality. In addition, reductions in the federal workforce could lower incomes and curb consumer spending in states with large concentrations of federal employees. Further, changes in tax policy, such as limiting the municipal bond tax exemption, could affect state revenues and increase borrowing costs. And actual and proposed cuts to federal grants—especially Medicaid, the largest source of federal funding to states—pose a direct threat to state budgets and services.

Some proposed and enacted federal actions have already led several states to lower their revenue forecasts. Colorado, for instance, reduced its projected economic growth for calendar years 2025 and 2026, citing “ elevated uncertainty around tariffs.” And Indiana cut its fiscal 2026 revenue forecast by nearly $1 billion on concerns over slower projected job, wage, and personal income growth through the biennium, driven in part by the expected impacts of federal policy changes. At least 22 other states also have adjusted their revenue forecasts downward amid growing economic and federal uncertainties.

Two fiscal management tools can help states better evaluate their exposure to federal policy shifts and the long-term affordability of pandemic-era budget commitments:

- Long-term budget assessments help policymakers identify challenges that can build over time.

- Budget stress tests help leaders assess how different economic scenarios would affect their budgets and how much to set aside in their rainy day funds.

Changes since the pandemic’s onset

The start of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 abruptly ended a nearly continual stretch of annual growth since 2010 when state tax revenue began recovering from the Great Recession. Aggregate state tax revenue from April through June 2020 was an extraordinary 25.4% lower than in the same quarter of 2019—the steepest single-quarter plunge in at least 25 years.

But much of the sudden shortfall resulted from the federal government’s decision—copied by nearly all states—to delay that year’s income tax filing deadline until July 15, which pushed large sums of personal and corporate income tax payments into the first quarter of fiscal 2021 and aggravated the strain on many states’ fiscal 2020 budgets. In the face of tremendous uncertainty, states forecasted multiyear revenue declines comparable to or more severe than those experienced as a result of the 2007-09 recession. But as the pandemic progressed, national tax revenue rebounded swiftly by historical standards—recovering about five times faster than it did after the 2007-09 recession.

Tax collections continued to exceed expectations in budget years 2021 and 2022, posting the highest and second-highest annual growth rates of the past 25 years, respectively, and bringing state tax revenue to record highs, while historic rainy day fund balances and federal aid to state governments gave state budgets extra breathing room.

Of the various factors that contributed to these higher-than-expected collections, unprecedented federal aid to businesses and unemployed workers, a shift in consumer spending patterns from purchases of often-untaxed services to typically taxable goods, and widespread conservative revenue forecasts were the primary catalysts. States’ relatively recent authority to collect sales taxes from out-of-state online sellers, quicker-than-anticipated recoveries in the stock market and employment, and job stability in higher-wage professions that were able to pivot to remote work also played a significant role.

Natural resource-dependent states—such as Alaska, North Dakota, and Wyoming—and those reliant on tourism—such as Hawaii and Nevada—had some of the deepest and longest-running declines in tax revenue. Reduced travel in the early stages of the pandemic hurt businesses and jobs in the leisure and hospitality industries and lowered demand for fuel, further depressing tax revenue in energy states that were already coping with pre-pandemic declines in oil and gas prices. Starting in the second half of 2021, however, rising energy prices and increasing tourism boosted these states’ recoveries.

The years of momentous tax revenue growth came to an end in fiscal 2023, when inflation-adjusted tax revenue fell compared with the prior year—the only time in at least 40 years that real annual tax revenue has declined outside of a recession. Tax revenue fell again in most states in fiscal 2024, marking the first time in at least 50 years that states experienced back-to-back real annual declines unrelated to an economic downturn.

Why Pew assesses state tax revenue trends

Tax revenue serves as the primary source of funding for most states. By tracking tax revenue trends, Pew provides policymakers and analysts with insights into the long-term financial health of their states, because revenue directly affects states’ capacity to provide residents with core public services—such as education, healthcare, and infrastructure—and to fund other policy priorities.

Understanding long-term trends can also help state leaders judge whether their budgets are on a sustainable path and can support better-informed fiscal planning and policy formulation. Policymakers should assess the factors behind tax revenue deviations from long-term trends—overall and for particular revenue streams—to understand whether revenue variations stem from policy changes, external factors beyond their immediate control—such as demographic shifts—or both. And to help ensure their state’s long-term fiscal sustainability, lawmakers should also examine whether these deviations are the result of one-time or temporary factors or whether they represent a more structural change that is likely to persist without policy action.

Justin Theal is a senior officer and Alexandre Fall is a senior associate with The Pew Charitable Trusts’ Fiscal 50 project.