Threats to a Florida River Also Imperil One of the World’s Rarest Honeys

Restoring the Apalachicola River’s flow could save bee farmers and help oyster harvesters downstream

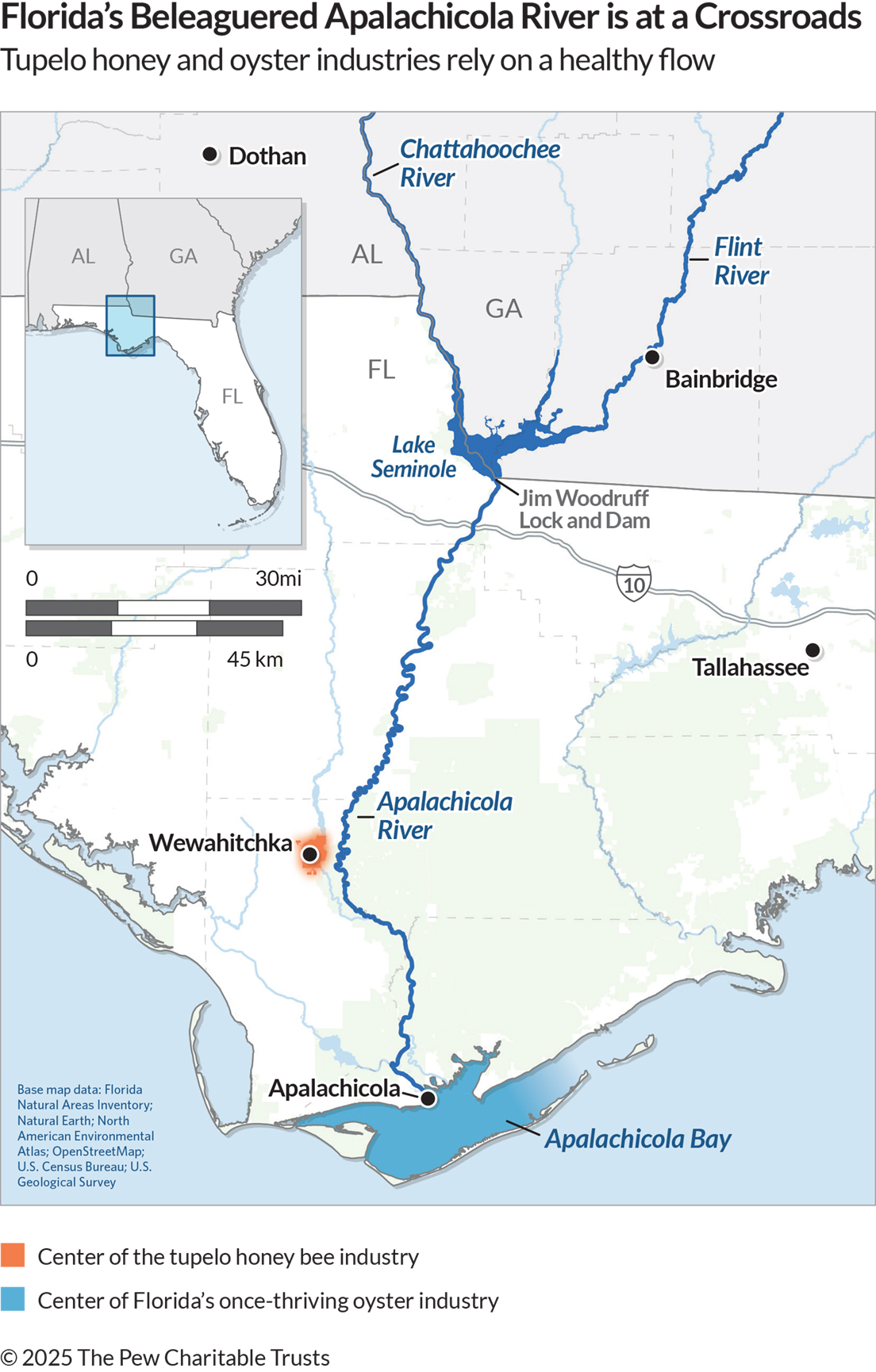

Gary Adkison approaches a scrub oak swarming with about 5,000 bees on his farm in Florida’s Panhandle. Barehanded, he reaches in and grabs a fistful of live bees—which crawl through his fingers and onto his wrist—and pours them into the hand of a shocked visitor. Welcome to Blue-Eyed Girl Honey, Adkison’s farm in the small rural community of Wewahitchka, the epicenter of Florida’s famous tupelo honey industry, near Apalachicola.

“They’re calm,” he says of the bees in his reassuring Southern drawl. “They’re not busy right now. They’re not producing honey or protecting babies. Whenever they get tired of your hand, they’ll be done.”

Moments later, the bees fly to the tree, Adkison shakes the branch, and the insects drop into a box where, if all goes according to his plan, they’ll soon produce tupelo honey.

The Apalachicola basin is home to one of the world’s largest concentrations of Ogeechee tupelo trees, the source of the delicacy honey. But many of the trees, which bloom for only a few weeks every spring, are dying. This is, in part, because the 107-mile Apalachicola River—which helps sustain these trees—is suffering from reduced flow because of drought, high water demand from homes and farms, and dredging that has altered the river’s natural pathways. All of these problems have persisted for decades.

Ogeechee tupelos rely on healthy swamps, fed by the Apalachicola, to survive. But sediment from dredging has formed a barrier between the river and those swamps, leaving many tupelo trees parched, especially during prolonged periods of low river flow.

“The tupelos are starving,” says Adkison, who runs the business with his wife, Pam Palmer. “All the veins stemming from the river that feed the tupelos—you can walk across them most of the year. The tupelo are our livelihood, and there may not be trees left. You’re talking about taking an ancestral lifestyle away.”

The economic impacts of such a die-off would be enormous for dozens of tupelo honey businesses in these communities, and they aren’t the only businesses suffering from the waterway’s plight.

Apalachicola Bay—where the river spills into the Gulf—once supplied 90% of Florida’s wild-caught oysters and 10% of those harvested in the U.S.

But in 2013, Apalachicola oyster populations began a devastating decline because of multiple problems, including overharvesting, hurricanes, pollution, sediments that smother the mollusks, and saltier conditions caused by low river flows. Florida fishery managers closed the bay to oyster harvesting in 2020. Now, with oysters showing small signs of recovery, fishery officials are considering reopening it next year to limited oyster harvesting, probably for only a short season.

“I don’t see that it will ever be as good as it used to be,” says fourth-generation oyster harvester Shannon Hartsfield, who gave up oystering when the populations plummeted and turned to jobs focused on restoring the bay. “My dad’s 77 now, and he will never be able to go back to oystering. My son was oystering when he was younger, but now he’s a welder. Reopening is only going to be a short season. And all it takes is one more drought to put us back in a bad situation again.”

The Apalachicola River has played center stage in political and legal disputes for decades. Three states rely on the river system: The Chattahoochee and Flint rivers in Georgia and Alabama flow into the Apalachicola at the Georgia-Florida state line, and if Georgia and Alabama take more water, Florida gets less. This water deficit is even worse when rain is scarce upstream.

These tristate water wars, which reached all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court twice, left the three states with water allocations that still fuel discontent and stand as a backdrop to two current-day issues.

The first is the way the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers manages flows in the Chattahoochee River by storing and releasing water through several federal dams. New research could help the Corps better understand when, where, and how it could manage this water to improve the health of the river’s ecosystems, particularly in Florida.

The Pew Charitable Trusts and university researchers from Florida and Louisiana are developing a project to identify the amount and timing of fresh water that a variety of plants and animals need, particularly those whose populations are imperiled by river management and flood plain conditions. Better management of river flows could help improve conditions not only for tupelo trees but also for oysters, freshwater bass, crawfish, threatened Gulf sturgeon, and endangered mussels.

The second issue is a Corps plan to restart dredging of the river, which had stopped in 2002, to accommodate a potential increase in the numbers of barges traveling from the Gulf to Georgia and Alabama.

But more dredging—and the sediments that it creates—could aggravate one of the river’s main problems: Its flood plains are clogged.

Under normal conditions, water spills into channels, sloughs, and flood plains that can naturally store water for drier times. But during lower flows, many of these side pathways are blocked by sediments that have built up into bars or small hills along the river’s edge.

Although the Corps stopped dredging more than two decades ago, these piles of sediment still erode into the river, drying habitat normally used by fish and other wildlife and further choking off the flood plains. This, in turn, results in hardwood trees such as willows and oaks flourishing in areas that should be dominated by swamp species such as cypress and tupelo.

But the sediment problem can be fixed. The Slough Restoration Project led by the nonprofit advocacy group Apalachicola Riverkeeper, funded in 2020 by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund, focuses on removing sand, debris, and trees from three slough systems in the Apalachicola basin to reconnect them with the river. Early results from this work show that water is moving several miles into the restored portions of the sloughs even during lower flows, creating better habitat and connections with the flood plains.

Additional slough restoration along the river could help oysters downstream. Water moving through flood plains carries nutrients to the bay, helping to feed oysters and the entire bay ecosystem. Further, too much sand moving through the river can smother oysters. Hartsfield says that restoring steady river flows and removing sand from the banks of the river are key. He supports projects that would pump some of the accumulated sand far enough off the riverbanks to prevent it from eroding back into the river, which would also make it easier for counties and others to use the sand—for example, in construction.

“No matter what, you still have to have the river flowing,” Hartsfield says. “Every time you do a little something, it can help. After a lot of small things, it starts to add up.”

Restoration projects take time, money, and cooperation among governments, scientists, conservationists, and others. Beekeepers Adkison and Palmer hope that people understand the importance of the river’s recovery, because a healthy ecosystem means prosperous communities.

“If the Apalachicola basin is changed to the point that the natural habitats along it cannot survive, then that’s the end of tupelo,” Palmer says. “I would be so hopeful if we could emphasize saving the habitat and recognize that the veins and arteries feeding the river are its lifeblood. But people won’t know how important all this is until it’s gone.”

Chad Hanson works on The Pew Charitable Trusts’ U.S. conservation project.