How States and Cities Decimated Americans’ Lowest-Cost Housing Option

The intertwined history of single-room occupancy and homelessness in the U.S.

Overview

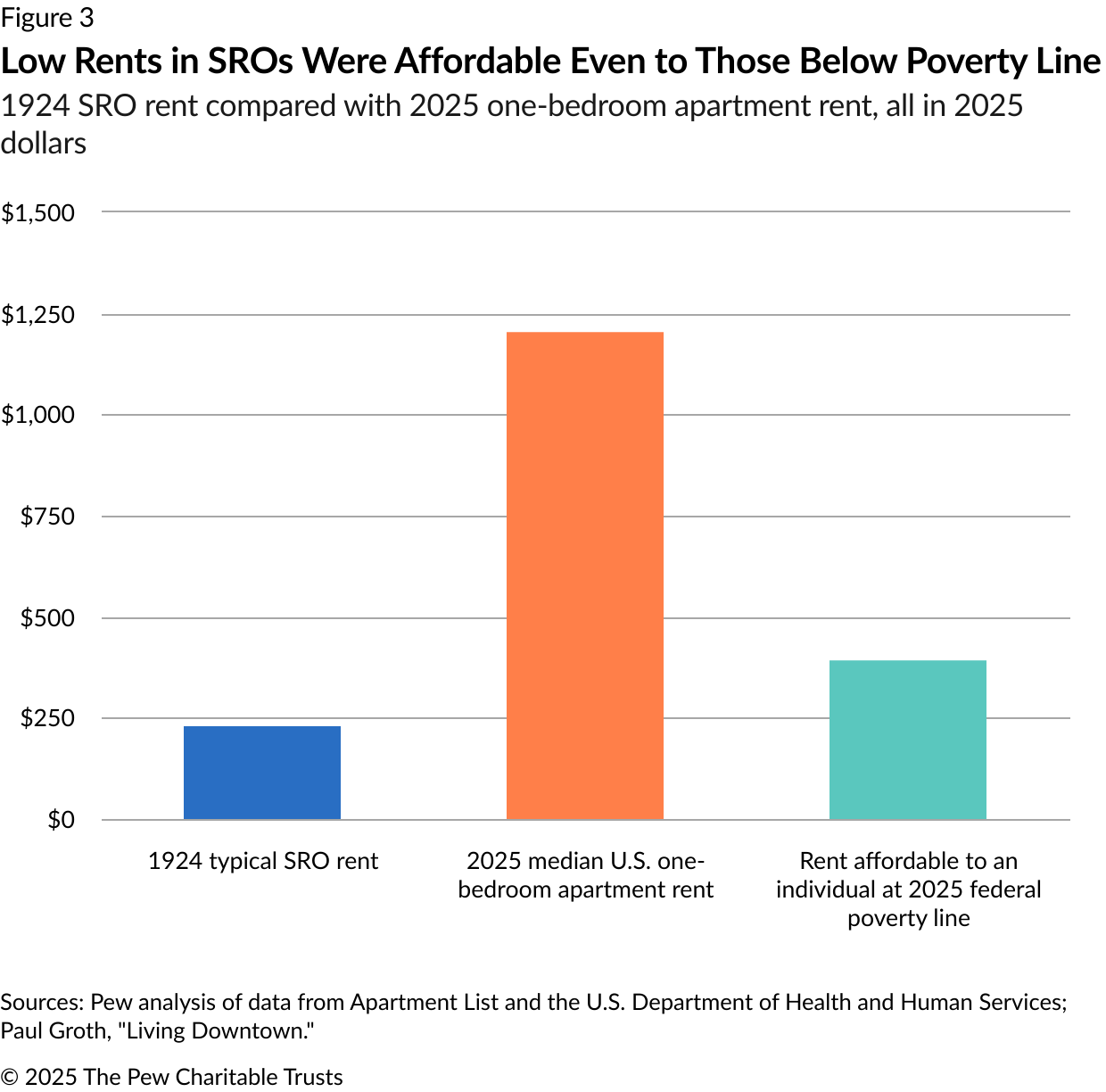

Low-cost micro-units, often called single-room occupancies, or SROs, were once a reliable form of housing for the United States’ poorest residents of, and newcomers to, New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and many other major U.S. cities. Well into the 20th century, SROs were the least expensive option on the housing market, providing a small room with a shared bathroom and sometimes a shared kitchen for a price that is unimaginable today—as little as $100 to $300 a month (in 2025 dollars).

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, landlords converted thousands of houses, hotels, apartment buildings, and commercial buildings into SROs, and by 1950, SRO units made up about 10% of all rental units in some major cities. But beginning in the mid-1950s, as some politicians and vocal members of the public turned against SROs and the people who lived in them, major cities across the country revised zoning and building codes to force or encourage landlords to eliminate SRO units and to prohibit the development of new ones. Over the next several decades, governments and developers gradually demolished thousands of SROs or converted them to other uses, including boutique hotels for tourists. And as SROs disappeared, homelessness—which had been rare from at least the end of the Great Depression to the late 1970s—exploded nationwide.

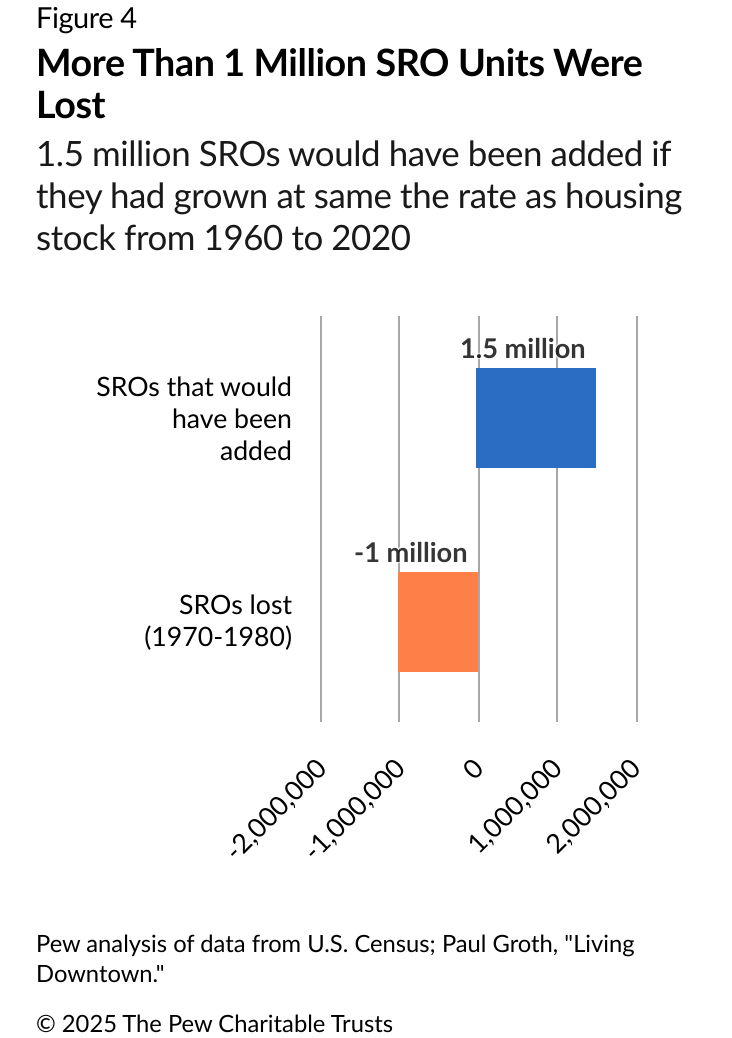

Now, as a nationwide housing shortage has pushed rents and homelessness to historic highs, some states and localities are reconsidering the value of lower-cost, small units with shared kitchens, bathrooms, and amenities. Ironically, had SROs grown since 1960 at about the same rate as the rest of the U.S. housing stock, the nation would have roughly 2.5 million more such units—enough to house every American experiencing homelessness in a recent federal count more than three times over.

As governments throughout the United States seek to fill the gap in low-cost housing, one promising and inexpensive model is gaining traction: making shared housing legal, as it was for most of U.S. history. And one version of shared housing—converting some of the vast supply of office space left empty since the COVID-19 pandemic—looks especially promising: A single office building conversion could add hundreds of low-cost homes near jobs and transit, while a large high-rise could add more than 1,000 homes. Several states have passed laws in the last few years to remove local legal barriers to building SROs or converting certain existing buildings into SROs.

This brief explores the history of SROs and their close relationship with homelessness. It also looks at strategies for adding large quantities of inexpensive housing units to meet the needs of the nation’s most vulnerable residents as well as others seeking low-cost housing.

Housing costs drive homelessness

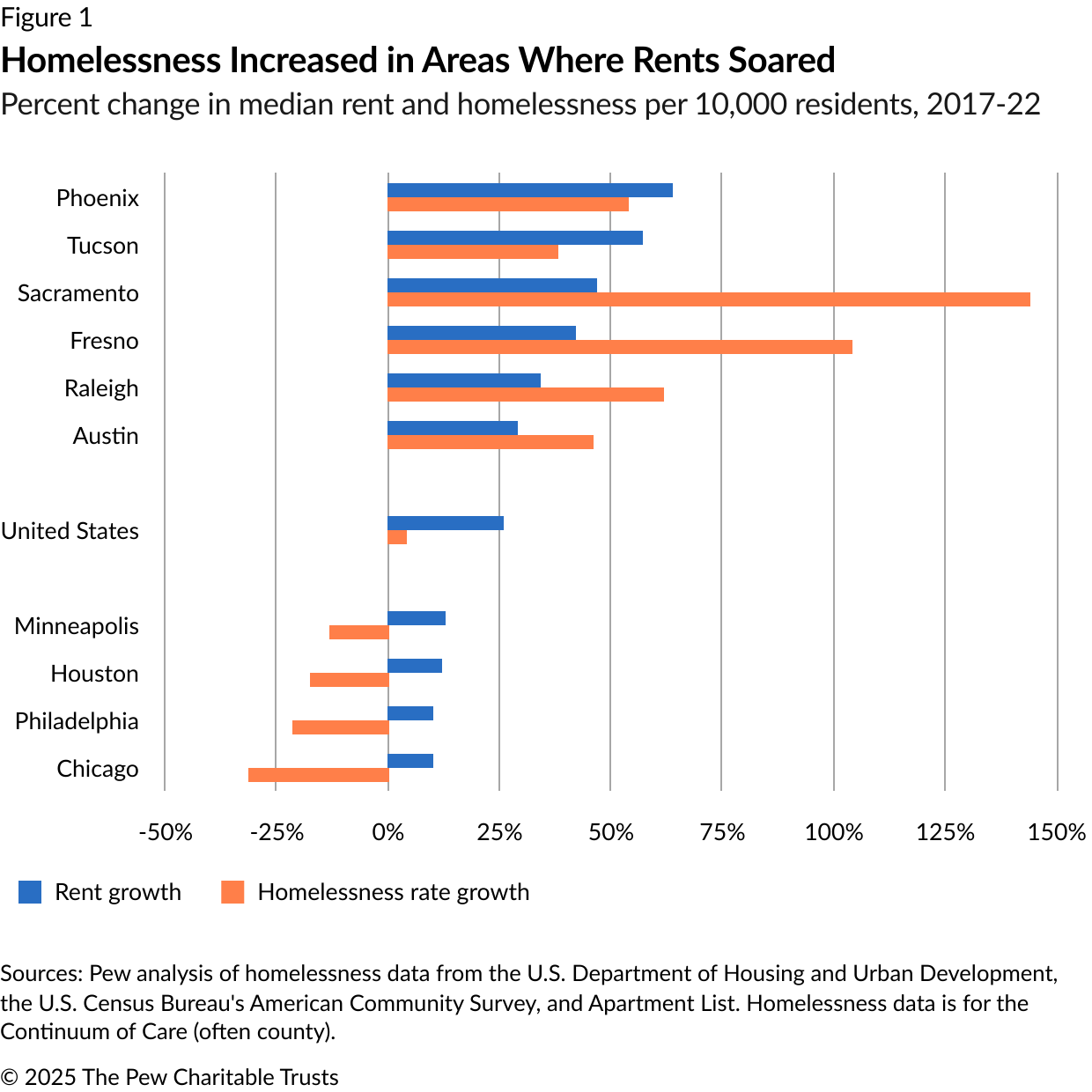

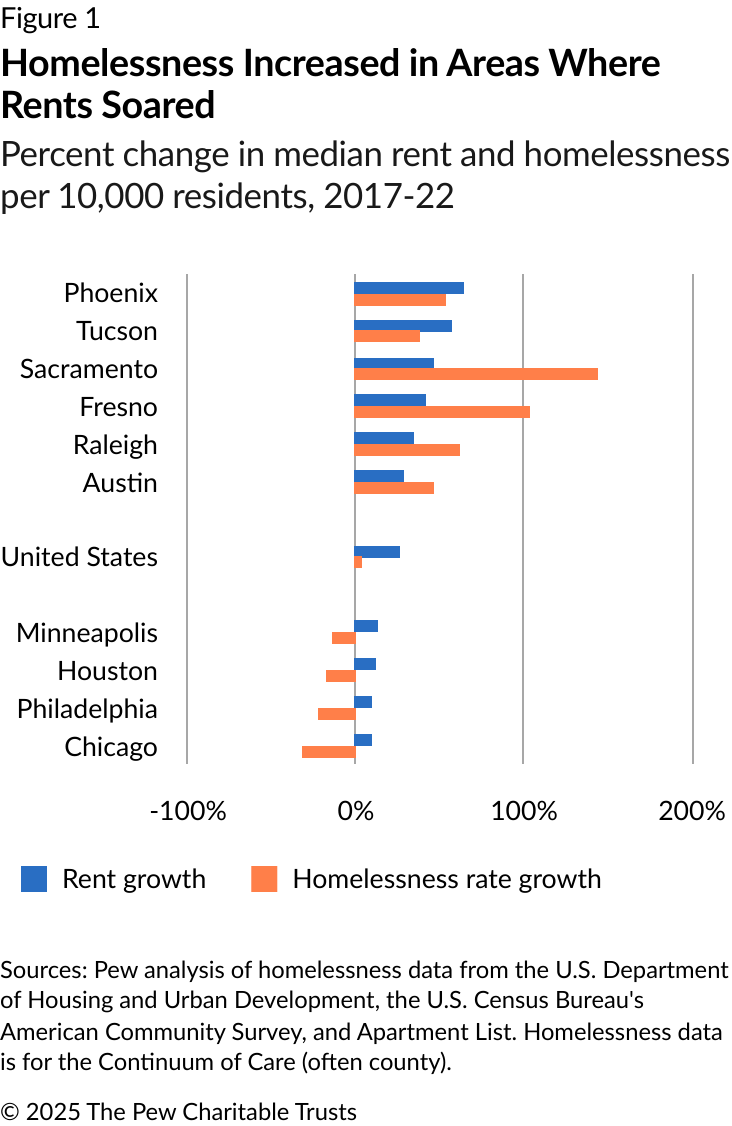

A wealth of research has examined the causes of homelessness over the past two decades. These studies consistently find that the cost of housing is by far the primary driver. For example, several studies have concluded that an area’s median rent correlates far more closely with its homelessness rate than factors such as weather, poverty rate, and rates of mental illness or substance use.

One study found that a $100 increase in median rent was associated with a 9% increase in homelessness.1 Another found that as rent-to-income ratios increase, homelessness increases in tandem.2 A separate study found a strong relationship between home prices and homelessness.3 Several studies have found low rental vacancy rates strongly predict high levels of homelessness.4 And when rents are high, families squeeze more people into smaller spaces, with less room to help struggling friends and relatives.5 Salim Furth, a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, explains the link: “When housing is cheap, relatives and friends tend to have more space in their homes, enabling them to keep someone at risk of homelessness off the street. … When space is tight, the people forced out are those who are hardest to live with.”6

Frequent explanations for homelessness focus on an individual’s characteristics. Certainly, people experiencing homelessness have disproportionate rates of disabilities, mental illness, and substance use compared with the general population. But cities with an abundance of low-cost homes have far less homelessness than high-cost cities, despite having similar rates of disability, mental illness, and substance abuse.7 And, as noted earlier, even in New York, San Francisco, and other expensive places, homelessness was uncommon as recently as the 1970s, when those cities still had a large stock of SROs.

This relationship is apparent whether comparing cities or states.8 High-rent states such as California, Hawaii, and New York have persistently high rates of homelessness; states with low rents, such as Alabama, Mississippi, and West Virginia, have low rates.9 California’s rate of homelessness is more than 10 times Mississippi’s. The rate of homelessness in New York City and San Francisco is about 15 times that of Houston, which has the lowest rents among the largest U.S. cities. Memphis, Tennessee; Milwaukee; and Pittsburgh are three other cities that have rents lower than most U.S. cities; all have consistently maintained lower-than-average rates of homelessness.10 Nationwide, as rents rose, 2023 marked an all-time high in homelessness. That mark was eclipsed in 2024.

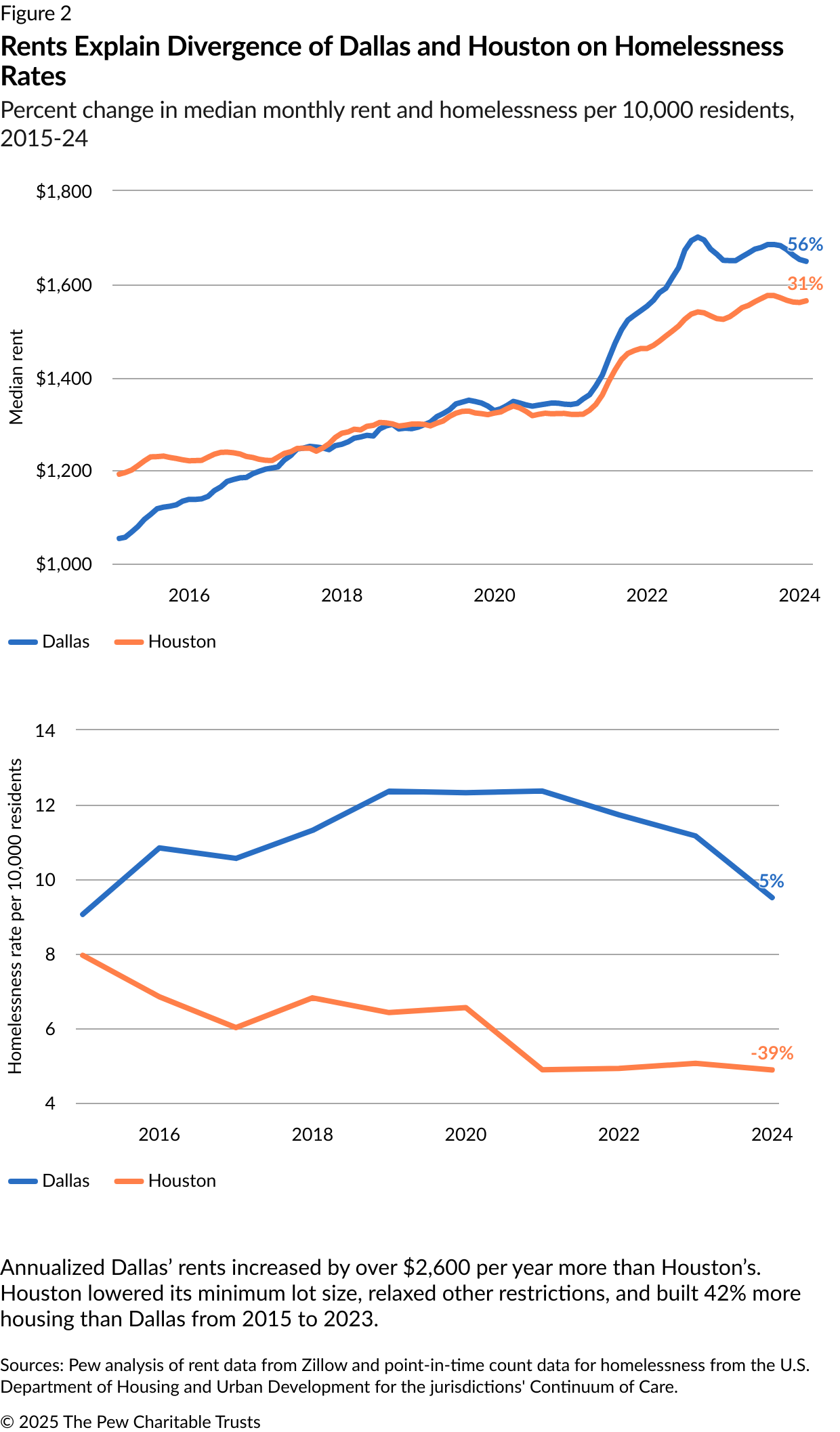

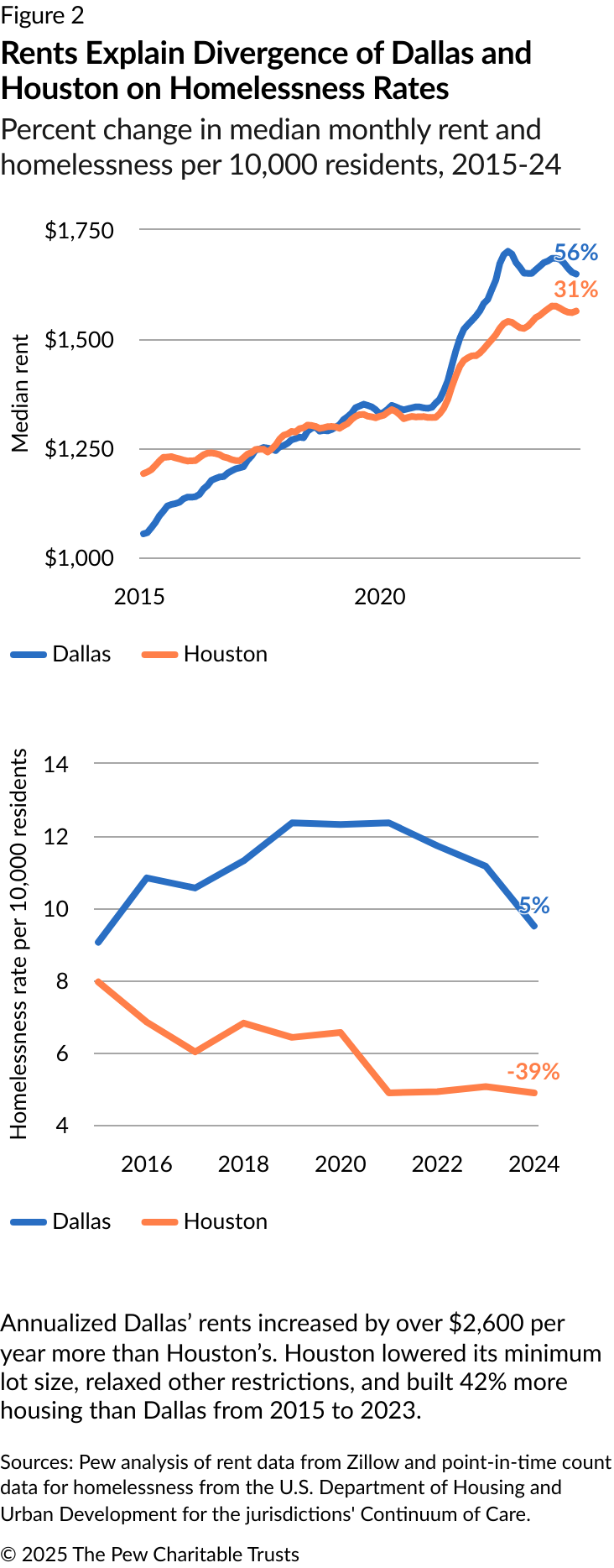

We can be sure that high housing costs are causing high homelessness because as housing costs change in a city or state, homelessness tends to move in tandem. When rents rise quickly, homelessness does too; when rents rise slowly but incomes keep increasing, that improves affordability, so homelessness declines. Supply and demand are the primary drivers of rent: When jurisdictions have added more housing, rent growth has slowed and homelessness has fallen.11 Where housing supply is limited, rent growth has been faster and homelessness more severe.

Another key indicator of the overwhelming relationship between housing costs and homelessness is the limited effectiveness of interventions targeted at other perceived causes of homelessness. An approach known as Housing First, for instance, showed great promise in the early 2000s. Previous attempts to address homelessness typically required individuals to participate in programs—drug treatment is a prominent example—before they received permanent housing. Housing First provided homeless individuals with a home along with access to social services such as counseling or treatment. The administrations of both George W. Bush and Barack Obama strongly supported Housing First, as did many states and cities. People receiving help via the Housing First strategy were far more likely to gain and keep a home than those that received conventional services.12 But when the 2007-09 Great Recession hit, homebuilding across the United States collapsed. The rate of homebuilding stayed low for the next decade and has never fully recovered. The resulting housing shortage drove rents higher—and with them, homelessness—despite the continued use of Housing First.

The contrasting experience of two large Texas cities demonstrates this phenomenon clearly. Houston’s permissive homebuilding laws enabled it to increase its housing supply and hold rents low. By contrast, Dallas added much less new housing than Houston and saw much faster rent growth. Both cities used Housing First to help tackle homelessness, but while Houston’s homelessness rate fell—the city’s rate is just a fifth of the U.S. overall and by far the lowest among large cities—Dallas’ homelessness rate increased.13

Raleigh, North Carolina, provides another example of the link between high rents and homelessness. Median rents there jumped 34% from 2017 to 2022, and homelessness rose 62%.14 But Raleigh enacted reforms that made it easier to build homes, including town houses, accessory dwelling units, and two- and three-unit buildings.15 Rents didn’t rise at all in Raleigh from the start of 2022 to the start of 2024, and homelessness fell 35%.16 Austin, Texas, had a similar experience, with rents and homelessness soaring from 2017 to 2022, but after land-use reforms made it easier to add housing, Austin saw both rents and homelessness decline.17

Extensive research has shown that adding housing supply, as Houston has done, slows rent growth, improving affordability. The main mechanism for this is that as new housing is added, there is less competition for older housing, which becomes more affordable. New housing helps improve affordability immediately, increasing supply and reducing demand pressure on the rest of the housing stock. In this way, more construction of new housing helps ensure a steady supply of lower-cost housing to accommodate lower-income residents. For example, when individual markets such as Austin and Phoenix saw a large number of new apartments delivered in 2023 (mainly projects that had started when interest rates were very low a couple of years earlier), rents declined across the board.18 But they fell most in older apartments with few amenities.

SROs and homelessness—an intertwined history

A new era gives rise to a new housing model

Homelessness first became an issue on a national scale in the 1870s. Continued upheaval in the aftermath of the Civil War and industrialization pushed more people into “riding the rails” on the nation’s new railroad system in search of jobs.19 The rise of these itinerant workers, in turn, drove the development of early rooming houses and residential hotels, particularly for Americans at the lower end of the income scale. Rooms could be rented by the night, week, or month.

Rooming and lodging houses were the first examples of SRO housing in the United States. Often, they were converted from single-family houses, tenement apartment buildings, or commercial office and warehouse properties. In other cases, single-family homes were not converted, but owners rented out individual rooms. American Enterprise Institute researchers have noted that before the 1920s, about one-third to one-half of urban residents were either boarders or rented part of their home to boarders.20 However, hotels designed to serve medium- and long-term tenants also began appearing in U.S. cities: Residential hotels became the most common SRO model throughout the country. Some residential hotels offered meal service in luxurious dining rooms, as well as regular laundry and maid service; less expensive hotels featured dark rooms without windows or even just a dry space on an open floor in a flophouse for 5 cents to 10 cents a night.21

Residential hotel construction peaked in the early 20th century in most cities. By the 1920s, many cheap hotels in big cities such as New York, San Francisco, and Chicago offered a mix of private rooms; large rooms converted to tiny, cubicle-style bedrooms with partitions that did not reach the ceilings; and open-air wards with rows of cots.22 At the time, a private room might rent for 25 cents to 40 cents a night and the semiprivate cubicles and open wards for 15 cents to 25 cents a night. That’s far less than anything available in modern U.S. cities: 40 cents in 1924 is the equivalent of about $7.40 in 2025, roughly $230 a month. That would be affordable even to a person living below the federal poverty line (defined as $15,650 in income for a one-person household in 2025).

Hotels nationwide were much different than they are today. They were much more likely to host long-term occupants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. One 1930 survey of hotels throughout the country found that long-term residents occupied an average of 20% of the rooms in the most expensive third of American hotels, and at least 75% of rooms in low- and midpriced hotels.23

In New York City, low-rent, single-room occupancy exploded during the Great Depression and World War II, when tens of thousands of people moved from the South and Puerto Rico to work in the city’s munitions factories and on major construction projects. By the 1950s, the city had more than 200,000 SRO units, accounting for more than 10% of the city’s rental housing stock.24 In 1986, 87,000 New Yorkers still lived in hotels, according to what was then the largest study of inexpensive hotels undertaken by a city government in the U.S. Across the five boroughs, 43% of SRO residents were under 40 years old and 32% were 40 to 60 years old; a third were Black; and a quarter were Latino.

During the same era in San Francisco, many long-term occupants of residential hotels were retired Filipino or Chinese laborers or newly arrived families from Southeast Asia.25 In 1977, 330 sheriff’s deputies and policemen showed up to evict 40 elderly Filipino and Chinese residents from the International Hotel, triggering outcry and concern as well as a congressional report.26

A backlash against SROs causes an explosion of homelessness

Even as SRO hotels and rooming houses provided homes for many of the poorest U.S. residents, problems arose. The housing was often of low quality and poorly maintained, and some neighbors complained about SRO residents.

Some politicians scapegoated SRO residents, increasingly portraying them as poor, dependent on alcohol or drugs, reliant on public welfare, transient, and immoral.27 This image was compounded by the condition of many SRO buildings, which even in the early 1900s were often run-down and neglected. Reformers blamed crowded apartments and unsanitary shared bathroom facilities for the spread of common diseases like pneumonia and tuberculosis.28 Some policymakers and activists viewed residential hotels and SROs as a public nuisance and a decaying form of housing that should be eliminated. “The SRO should not be accepted as lawful housing for any segment of our population,” an aide to New York City Mayor Robert F. Wagner reportedly said in 1965.29 “No community should equate such housing with the acceptable living standards of the 1960s.”

Many city and state governments began crafting policies in the 1950s and 1960s that encouraged property owners to convert SRO buildings to tourist-oriented hotels or traditional apartments. Newly enacted zoning codes and building codes made creating SROs illegal or economically unviable. Researchers have noted that market forces alone would have been unlikely to decimate the stock of SROs because they were profitable to operate when allowed and declined only when new laws targeted them.

The scale of the loss of low-cost housing in the second half of the 20th century is staggering. There is no reliable count of the number of SRO units lost before 1970; “estimates usually refer to ‘millions’ of rooms closed, converted, or torn down in major U.S. cities,” the historian Paul Groth said.30 He estimates that another million residential hotel rooms were destroyed or converted in the subsequent decade, from 1970 to 1980.31 Almost all of that housing was destroyed or converted to other uses in response to zoning and building code reforms or tax incentives enacted for the specific purpose of eliminating SROs.

New York City, for example, banned construction of SRO buildings and the creation of new SRO units from existing buildings in 1955. Over the next two decades, the city enacted a series of other building code and zoning changes, which raised the costs of operating SRO buildings and had the effect of encouraging owners to convert them to other uses.32 This meant that apartments in a building were required to have an average size much larger than SROs, in addition to the ban on new SROs. In the 1970s, New York City enacted tax abatements that gave SRO owners a financial incentive to convert SROs into rent-stabilized apartments with bathrooms and kitchens included (and higher rents). The tax break worked as intended, driving the conversion of 40 residential hotels a year.33 In response to the city and state incentives and regulatory changes, owners destroyed two-thirds of New York City’s remaining SRO units from 1976 to 1981, a state Assembly study found at the time.34

New York City was not alone. Starting in the 1960s, for example, San Francisco decided to redevelop South of Market, making way for what became the Moscone Convention Center and Yerba Buena Gardens—an area where 41% of the 240 resident families lived in hotels. Justin Herman, who led the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency from 1959 to 1971 and accelerated its urban renewal efforts throughout the city, was quoted as saying, “This land is too valuable to permit poor people to park on it.”35 Studies estimate that 40,000 residential hotel rooms were destroyed by urban renewal programs in San Francisco—including more than 6,000 in just five years from 1975 to 1980—though the city did not maintain public records on the total.36

Similarly, Seattle demolished half of its SROs downtown—16,200 units—between 1960 and 1973.37 A catastrophic fire at the five-story Ozark Hotel in March 1970 led to a wave of demolition. After the fire, Seattle changed its building code to require either sprinklers or fire-resistant doors and stairways for buildings where residents lived on the fourth story or higher. These costly upgrades made it challenging to operate inexpensive units. The city demolished 5,000 SRO units during its enforcement of this one code change—the so-called Ozark fire code—in the 1970s.38 Several other building code mandates followed, prompting many residential hotel owners to abandon their buildings rather than incur the higher costs to maintain them; by 1982, nearly 30% of the remaining units in downtown Seattle sat vacant.39

Other notable examples include Boston, which lost nearly 90% of its SROs from the 1950s to 1985; Chicago, which lost 80% of its SRO units—32,000 rooms—between 1973 and 1984; and San Diego, which lost about 1,247 units from 1976 to 1984.40 Cincinnati is estimated to have lost more than 2,000 units during the 1970s, about 42% of its SRO stock.41

As the nation’s least expensive source of housing disappeared, homelessness soared in major cities across the United States. In New York City, for example, the number of homeless residents increased from a barely visible population to almost 30,000 by 1987.42 About half of men entering homeless shelters in the city in 1980 reported they had previously lived in SROs. The sudden loss of SROs and commensurate rise in homelessness prompted an advocate in New York to remark: “The people you see sleeping under bridges used to be valued members of the housing market … they aren’t anymore.”

A series of social, political, and economic changes also battered large U.S. cities in the 1980s, contributing to the homelessness epidemic. State psychiatric hospitals released people suffering from mental illness without adequate provisions for outpatient care. Property owners abandoned inner cities, leaving empty buildings. AIDS arrived. The federal government reduced subsidies for public housing and rental assistance and made it more difficult for people with disabilities to qualify for Supplemental Security Income (SSI). Cuts to SSI—which largely benefits disabled people and those over 65—and a tightening of eligibility for disability payments in the early 1980s added to the financial instability of many struggling Americans.43

In some regions, especially the Northeast, homelessness became less visible after the initial surge in the early 1980s, as cities and towns increased shelter capacity. As a result, a larger share of people experience sheltered rather than unsheltered homelessness in cold-weather cities, especially in the Northeast. But the life outcomes of people without homes who live in shelters are little better than for those without homes who live on the street. Both groups lose decades of life expectancy.44

By the 1990s, only a tiny fraction of SRO hotels were left in the United States. Housing costs were lower in the 1990s than today (even in income-adjusted terms), but the lack of SROs meant that homelessness continued unabated. With the lowest rung on the housing ladder missing, many people could not afford rent for conventional apartments or houses, including shared ones.45

Nationwide, homelessness has been rising since 2017 as housing has become increasingly more expensive. Between 2022 and 2023 alone, the number of homeless people in the U.S. rose by 12%, to more than 653,000, according to the annual count compiled by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).46 That meant 20 in 10,000 Americans were experiencing homelessness on a single night in January, the most since HUD began counting in 2007.47 In 2024, the homelessness rate jumped to 23 in 10,000.48 More than a third of all individuals identified in the HUD count were living on the street, in abandoned buildings, or beneath bridges—or, in the words of the HUD report, “in places not meant for human habitation.”49 The 2023 record was broken in 2024, when HUD released data identifying 771,480 homeless Americans, an 18% increase from 2023. These numbers are widely considered an underestimate.

2.5 Million Missing Low-Cost Units

In 1960, when the loss of SROs was just beginning, there were 6.9 million single-person households in the U.S. By 2023, that number had reached 38 million.50 In that time, the nation’s housing stock grew by a factor of 2.5, from 58.3 million homes to 145.4 million. Meanwhile, more than 1 million SRO units were destroyed or converted to other uses from 1970 to 1980 alone. Had the SRO stock grown at a similar rate as the rest of the nation’s housing supply, the U.S. would have added 1.5 million units rather than losing 1 million, for a net change of 2.5 million more SRO units. That’s more than triple the number of people experiencing homelessness in HUD’s 2024 count.51

New housing is usually expensive, and as homes get older, they get more affordable as high-income residents move into costly new housing. SROs, though, can be created at a much lower price point than other types of housing because the units are small and residents generally share bathrooms and kitchens. The same building using an SRO-style layout can simply fit more units that cost less than conventional apartments. Historically, SROs usually weren’t new construction; instead, they were created from other residential or commercial buildings whose original use no longer made sense. As the U.S. finds itself with more than a billion square feet of vacant office space in 2025, there is an opportunity to do what property owners did in the late 1800s and early 1900s: convert underused space into low-cost, well-located SRO-style housing units. It’s not possible to create all 2.5 million missing units this way, but SRO layouts are so efficient that a single high-rise building can hold more than 1,000 units.

Full circle: Surging homelessness drives renewed interest in SROs

As early as the mid-1980s, the problem of homelessness in New York City had gotten so severe that legislators tried to reverse course on SROs.52 The city government passed Local Law 19 in May 1983, adding protections for SRO tenants. The city ended tax benefits for converting SROs in 1983.53 Eventually, the City Council banned the conversion, alteration, demolition, or warehousing (holding units vacant for years to make them eligible for conversion or demolition) of SRO units altogether. But the New York Court of Appeals ruled these bans unconstitutional because they prevented property owners from determining how their buildings could be used.54 Similarly, Chicago officials passed an SRO preservation ordinance to discourage conversions or sales of SROs in 2014, but by that time, the large majority had already been lost.55 The city’s zoning and building codes made it challenging to build new ones.

Although New York City’s policy to block owners of SRO buildings from converting them to new uses was overturned by courts, city officials took other steps to preserve SROs even as different city laws banned the creation of new ones. One of these statutes was an anti-harassment policy instituted decades ago, which required that landlords looking to convert SROs prove that they had not harassed tenants to move out, such as by making living conditions intolerable or failing to perform needed maintenance. But this policy, known as a Certification of Non-Harassment (CONH), added costs and administrative requirements for landlords, contributing to the difficulty of operating SROs. The program was changed and expanded in 2018 to require that landlords also get a CONH before renovating SRO buildings.56 Ultimately, however, neither the city nor the state has taken effective steps to rehabilitate or meaningfully expand the city’s SRO stock.57

Despite all of this, New York City probably still has the largest remaining stock of SRO hotels and rooming houses in the country. A paper from the Furman Center at New York University estimated that there were as many as 30,000 SRO units remaining in the city in 2014.58 The city regulates SROs as part of its rent stabilization program, meaning owners can raise rents by only a low amount each year and need to file documentation with the city on each unit’s rent. In 2022, the state housing agency reported 322 regulated SRO buildings with 11,051 units, of which nearly half—more than 5,300—were rent-stabilized.59 The median monthly allowable rent for these units was $1,018 in 2022, compared with $1,641 for a regular rental apartment in the city in 2023 (including public housing, rent-controlled housing, subsidized housing, and conventional, market-rate housing).60

Although New York has the most existing SROs, several Western states have been the first to pass new laws to enable construction of single-occupancy units. State governments have increasingly stepped in to require that certain types of housing be allowed because localities have not taken adequate steps to address the housing shortage.61 That was rare in the past: From 2011 to 2016, all states combined passed an average of one law per year to allow more homes; from 2023 to 2024, that number jumped to 48 for all states combined. In 2024, the Washington Legislature passed legislation requiring cities to allow SRO-type housing wherever multifamily housing of six or more units is permitted, beginning in late 2025.62 This legislation authorizes small units with shared bathrooms and kitchens; limits off-street parking requirements to one spot for every four bedrooms; and prohibits all parking mandates for buildings within half a mile of a major transit stop.63 The bill was one of several that Washington passed to ensure that some types of lower-cost housing are allowed even where local governments had blocked them before or residents fought development.64 Seattle had previously allowed development of low-cost micro-units, for example, but city officials in 2013 enacted laws that effectively prohibited them.

The Oregon Legislature enacted similar legislation in 2023, allowing micro-units in all areas zoned for residential use in cities across the state, including an SRO with up to six units on a parcel zoned for single-family use.65 As of Jan.1, 2025, Hawaii communities must allow the conversion of commercial properties into SRO housing.66 Montana took a somewhat different approach, passing legislation in 2023 that created a housing “menu” for its cities and towns to choose from—a series of options from which cities must choose at least five to allow more housing.67 One of these is to permit co-living micro-units.

Perhaps the simplest method of creating low-cost shared housing is to allow unrelated individuals to share a house in the same way that relatives are allowed to share a house.68 But many communities limit the number of unrelated people who can live together—in some places, to as few as two. Such laws make sharing a house for a group of roommates—which usually enables rents lower than having an individual apartment—illegal. The U.S. has a record number of unused bedrooms, but many cannot be rented because of restrictions on house sharing by unrelated roommates, even if that would be the most profitable use for the landlord and the most affordable option for the tenants.69 To enable this low-cost housing option, Iowa, Oregon, and Colorado all passed bipartisan legislation to strike down local codes that prohibit house-sharing (in 2017, 2021, and 2024, respectively).70

In all of those cases, states have stepped in when localities did not act, authorizing lower-cost housing and limiting the ability of local governments to ban inexpensive housing. The aim of those laws is to increase the rental market for low- and moderate-income residents and make more use of existing housing stock. If these bills succeed, and a large number of micro-units reach market, their rents will likely be low, since individual rooms, when available, usually rent for far less than houses or apartments.71 And while these units are intended for individuals rather than larger households, Manhattan Institute researchers have noted that they could “help release three- and four-bedroom apartments currently occupied by unrelated millennials” for use by families.72

Individual rooms also cost less to build than apartments and houses. In October 2024, February 2025, and April 2025, The Pew Charitable Trusts and Gensler, a global architecture, design, and planning firm, released three reports that described how vacant office space in large cities could be converted into low-cost micro-units with shared bathrooms and kitchens—essentially a safe, clean, code-compliant, well-located version of SROs.73 The projected rents for rooms in these converted buildings are about half of the median in the studied markets and therefore affordable to residents earning 30% to 50% of the area median income, with much lower public subsidies than are generally required to build low-cost apartments.74 The small unit size (120-220 square feet), shared bathrooms, and shared kitchens would lead to development costs at least 50% lower than the cost of building new studio apartments. If these modern SRO rooms were priced right, a wide range of residents might elect to live in conveniently located downtown housing. But this option could make the biggest difference for low-income residents who are now struggling to afford any type of home.

Many Americans are struggling. Nationwide, about 11 million tenant households—one-fourth of all renters in the U.S.—are considered extremely low-income, earning at or below the federal poverty line of $15,650 for a single person or $32,150 for a family of four or if they earn less than 30% of their area’s median income. According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, the United States is short more than 7 million rental units that are affordable for those households.75 California has the nation’s largest extremely low-income renter population, with nearly 1.3 million households.76 And of those, more than three-quarters are severely “rent burdened,” meaning they spend more than 50% of their income on housing costs. New York has the second-highest number of extremely low-income renter households, at just under 1 million.77

New York State has taken fewer steps than some other states to house its poorest citizens. In 2023, Governor Kathy Hochul (D) announced $50 million in funding to help landlords repair 500 SROs across the state, a quiet reversal of long-standing anti-SRO policies.78 And for the first time in decades, New York City has removed one of the barriers to new SRO units as part of a slate of zoning changes, called City of Yes for Housing Opportunity. City of Yes, which broadly aims to allow modestly more residential development throughout New York’s five boroughs, removed the minimum average unit-size requirements in Manhattan south of 96th Street and in downtown Brooklyn.79 But New York City’s building code still has other obstacles to converting space into SRO-style housing.

Even with these efforts to add low-cost housing and reduce homelessness, from 2022 to 2023, the U.S. added fewer than 37,000 beds specifically to help individuals transitioning out of homelessness, an increase of just 7%. Providing safe, affordable homes for the hundreds of thousands of Americans experiencing homelessness will require far more ambitious policy initiatives informed by a recognition of the vital role SROs have played in U.S. housing for a century and a half.

Conclusion

Housing costs are by far the strongest determinant of homelessness. Areas with high costs have high homelessness rates, and areas with low housing costs have low homelessness rates. When rents rise quickly, homelessness does, too. When rent growth is contained, homelessness drops. Increasing the housing supply helps hold rent growth down, making housing more affordable. But adding low-cost housing is especially helpful in preventing homelessness.

When SROs were widespread in the United States, even the nation’s poorest residents could usually afford a home. But as targeted zoning, building codes, and tax incentives led to the demise of the SRO housing stock, homelessness became commonplace. Had the country’s stock of SRO housing merely grown in line with other types of housing, the U.S. would have about 2.5 million additional low-cost homes—more than triple the number of people counted as homeless in January 2024.

In an effort to bring back low-cost housing, some states that are struggling with high homelessness rates have begun to remove legal barriers to the development of co-living buildings that feature private micro-units with shared bathrooms and kitchens. If more states and cities reduce regulatory barriers to this type of housing—and ideally provide incentives to kick-start its development—the nation has a real opportunity to once again make homelessness rare and ensure that the most financially vulnerable Americans, such as those earning minimum wage or receiving Social Security benefits, can afford a place to live.

External reviewers

This brief benefited from valuable insights and feedback from historian Jacob Anbinder, a Klarman postdoctoral fellow at Cornell University, and Joy Moses, vice president of research and evidence at the National Alliance to End Homelessness. Although they reviewed drafts of the brief, neither they nor any institutions with which they are affiliated necessarily endorse its findings or conclusions.

Acknowledgments

This brief was researched and written by housing author Rebecca Baird-Remba and Pew staff member Alex Horowitz, project director of The Pew Charitable Trusts’ housing policy initiative. The team thanks Pew colleagues Demetra Aposporos, Esther Berg, Laurie Boeder, Frank Clancy, Jennifer V. Doctors, Gabriela Domenzain, Chelsie Pennello, and Allie Tripp for providing important communications, creative, editorial, and research support for this work.

- “Homelessness: Better HUD Oversight of Data Collection Could Improve Estimates of Homeless Population,” U.S. Government Accountability Office, Aug. 13, 2020, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-433.

- Chris Glynn, Thomas H. Byrne, and Dennis P. Culhane, “Inflection Points in Community-Level Homeless Rates,” Annals of Applied Statistics 15, no. 2 (2021), https://wp-tid.zillowstatic.com/3/Homelessness_InflectionPoints-27eb88.pdf.

- “HUD Homeless Count Fails to Connect Dots on Supply and Displacement,” Edward J. Pinto, Jan. 3, 2024, https://www.aei.org/op-eds/hud-homeless-count-fails-to-connect-dots-on-supply-and-displacement/.

- John M. Quigley and Steven Raphael, “The Economics of Homelessness: The Evidence From North America,” European Journal of Housing Policy 1, no. 3 (2001): 323-36, https://escholarship.org/content/qt2dw8b4r3/qt2dw8b4r3_noSplash_a4686d01d6f0ce3406e61ab1a7f39933.pdf.

- Margot Kushel et al., “Toward a New Understanding: The California Statewide Study of People Experiencing Homelessness,” Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative, 2023, https://homelessness.ucsf.edu/sites/default/files/2023-06/CASPEH_Report_62023.pdf.

- “Why Housing Shortages Cause Homelessness,” Salim Furth, Dec. 5, 2024, https://worksinprogress.co/issue/why-housing-shortages-cause-homelessness/.

- Gregg Colburn and Clayton Page Aldern, Homelessness Is a Housing Problem: How Structural Factors Explain U.S. Patterns (University of California Press, 2022), https://www.ucpress.edu/books/homelessness-is-a-housing-problem/paper.

- “How Housing Costs Drive Levels of Homelessness,” Alex Horowitz, Chase Hatchett, and Adam Staveski, Aug. 22, 2023, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2023/08/22/how-housing-costs-drive-levels-of-homelessness.

- Tanya de Sousa and Meghan Henry, “The 2024 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress—Part 1: Point-in-Time Estimates of Homelessness in the U.S.,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2024, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2024-AHAR-Part-1.pdf.

- “How Housing Costs Drive Levels of Homelessness,” Alex Horowitz, Chase Hatchett, and Adam Staveski.

- “Minneapolis Land Use Reforms Offer a Blueprint for Housing Affordability,” Linlin Liang, Adam Staveski, and Alex Horowitz, Jan. 4, 2024, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2024/01/04/minneapolis-land-use-reforms-offer-a-blueprint-for-housing-affordability.

- B. O’Flaherty, “Homelessness Research: A Guide for Economists (and Friends)” (Department of Economics, Columbia University in the City of New York, 2018), https://sites.asit.columbia.edu/econdept/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2018/08/homelessresearchv2-080118.pdf.

- “Zoning Reform Can Reduce Homelessness,” Alex Horowitz and Lisa Marshall, Feb. 19, 2024, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/about/news-room/opinion/2024/02/19/zoning-reform-can-reduce-homelessness.

- “How Housing Costs Drive Levels of Homelessness,” Alex Horowitz, Chase Hatchett, and Adam Staveski.

- “Raleigh’s Zoning Reform Has Ushered in More Housing Options,” Zachery Eanes, June 21, 2024, https://www.axios.com/local/raleigh/2024/06/21/raleigh-sees-increase-in-townhouses-and-adus-from-zoning-reform.

- Tanya de Sousa and Meghan Henry, “2024 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report.”

- Joshua Fechter, “Austin Rents Have Fallen for Nearly Two Years. Here’s Why,” The Texas Tribune, https://www.texastribune.org/2025/01/22/austin-texas-rents-falling/.

- J. Bunch, “High Supply Apartment Markets with Less Severe Class A Rent Cuts,” https://www.realpage.com/analytics/class-a-rent-cuts-high-supply-markets/.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, “Appendix B: The History of Homelessness in the United States,” in Permanent Supportive Housing: Evaluating the Evidence for Improving Health Outcomes Among People Experiencing Chronic Homelessness (Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2018), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519584/.

- Edward Pinto and Hannah Florence, “The Decline of SROs and Its Consequences for Housing Affordability,” AEI Housing Center, 2024, https://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/The-history-of-SROs-FINAL-v2.pdf.

- P. Groth, Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels in the United States (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Permanent Supportive Housing.

- Paul Groth, Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels.

- Brian J. Sullivan and Jonathan Burke, “Single-Room Occupancy Housing in New York City: The Origins and Dimensions of a Crisis,” City University of New York Law Review 17, no. 1 (2013), https://academicworks.cuny.edu/clr/vol17/iss1/5/.

- Paul Groth, Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels.

- U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging, “Single Room Occupancy: A Need for National Concern,” 1978, https://www.aging.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/reports/rpt478.pdf.

- Malcolm Gladwell, “N.Y. Hopes to Help Homeless by Reviving Single Room Occupancy Hotels,” Los Angeles Times, April 25, 1993, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1993-04-25-mn-27098-story.html.

- Paul Groth, Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels.

- Malcolm Gladwell, “N.Y. Hopes to Help Homeless.”

- Groth, Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels in the United States.

- Ibid.

- Malcolm Gladwell, “N.Y. Hopes to Help Homeless.”

- Brian J. Sullivan and Jonathan Burke, “Single-Room Occupancy Housing in New York City.”

- Brian J. Sullivan and Jonathan Burke, “Single-Room Occupancy Housing in New York City.”

- “Real Estate Team’s Winning Project Envisions a More Inclusive San Francisco,” Georgetown University School of Continuing Studies, https://scs.georgetown.edu/news-and-events/article/7216/real-estate-teams-winning-project-envisions-more-inclusive-san-francisco.

- Groth, Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels in the United States.

- U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging, “Single Room Occupancy: A Need for National Concern.”

- “Arsonist Kills 20 and Injures 10 at the Ozark Hotel Fire in Seattle on March 20, 1970,” Greg Lange, Jan. 15, 1999, https://www.historylink.org/File/698.

- “Roots of a Crisis,” Sinan Demirel, June 29, 2016, https://www.realchangenews.org/news/2016/06/29/roots-crisis.

- “Small Rooms, Big Impact: Could SROs Help Fix Boston’s Housing Crisis?” Lucas Munson, Boston Indicators, March 13, 2025, https://www.bostonindicators.org/article-pages/2025/march/room-occupancy. The Brookings Institution, Henry Aaron and Charles L. Schultze, eds., Setting Domestic Priorities: What Can Government Do? (1992), https://www.brookings.edu/books/setting-domestic-priorities/.

- The Brookings Institution, Aaron and Schultze, eds., Setting Domestic Priorities.

- Jacob Pomeroy Anbinder, “Cities of Amber: Antigrowth Politics and the Making of Modern Liberalism” (doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, 2023), https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/37378071.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Permanent Supportive Housing.

- Ilina Logani, Bruce D. Meyer, and A. Wyse, “The Mortality of the Us Homeless Population,” Becker Friedman Institute for Economics at University of Chicago, https://bfi.uchicago.edu/insight/research-summary/the-mortality-of-the-us-homeless-population/.

- Edward Pinto and Hannah Florence, “The Decline of SROs and Its Consequences.”

- Tanya de Sousa et al., “The 2023 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress—Part 1: Point-in-Time Estimates of Homelessness in the U.S.,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2023, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2023-AHAR-Part-1.pdf.

- Tanya de Sousa et al., “2023 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report.”

- Tanya de Sousa and Meghan Henry, “2024 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report.”

- Tanya de Sousa and Meghan Henry, “2024 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report.”

- “HH-4. Households by Size: 1960 to Present,” U.S. Census Bureau, 2024, https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/tables/families/time-series/households/.

- This estimate is at the low end of what is likely necessary to meet Americans’ housing needs. In 1960, just 13% of U.S. households had one person. By 2020, that figure was 28%. Because single-person households have increased more than fivefold from 6.9 million in 1960 to 38.1 million in 2023, more single-room housing units are probably needed as an overall share of the housing stock.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Permanent Supportive Housing.

- Debra S. Vorsanger, “New York City’s J-51 Program: Controversy and Revision,” Fordham Urban Law Journal 12, no. 1 (1984), https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol12/iss1/3.

- Alan Finder, “Supreme Court Won’t Review S.R.O. Ruling,” The New York Times, Nov. 28, 1989, https://www.nytimes.com/1989/11/28/nyregion/supreme-court-won-t-review-sro-ruling.html.

- Emily Badger, “What Happens When Housing for the Poor Is Remodeled as Luxury Studios,” The Washington Post, Nov. 12, 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2014/11/12/what-happens-when-housing-for-the-poor-is-remodeled-for-millennials/.

- Local Laws of the City of New York for the Year 2018 (2018), https://www.nyc.gov/assets/hpd/downloads/pdfs/services/local-law-1-2018.pdf.

- Brian J. Sullivan and Jonathan Burke, “Single-Room Occupancy Housing in New York City.”

- Eric Stern and Jessica Yager, “21st Century SROs: Can Small Housing Units Help Meet the Need for Affordable Housing in New York City?,” Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy, 2018, https://furmancenter.org/files/Small_Units_in_NYC_Working_Paper_for_Posting_UPDATED.pdf.

- New York City Rent Guidelines Board, “2023 Hotel Report,” 2023, https://rentguidelinesboard.cityofnewyork.us/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2023-Hotel-Report.pdf.

- “2023 New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey: Selected Initial Findings” (New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development, 2024), https://www.nyc.gov/assets/hpd/downloads/pdfs/about/2023-nychvs-selected-initial-findings.pdf.

- Eli Kahn and Salim Furth, “Laying Foundations: Momentum Continues for Housing Supply Reforms in 2024,” Mercatus Center, 2024, https://www.mercatus.org/research/policy-briefs/housing-supply-reforms-2024.

- “Micro-Apartments Are Back After Nearly a Century, as Need for Affordable Housing Soars,” Hallie Golden and Claire Rush, March 21, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/micro-apartments-affordable-housing-homelessness-716346460edde132dd3701f8eda74331.

- Laurel Demkovich, “WA House Approves Bill to Expand Dormitory-Like Housing,” Washington State Standard, https://washingtonstatestandard.com/2024/02/07/wa-house-approves-bill-to-expand-dormitory-like-housing.

- “How Seattle Killed Micro-Housing,” David Neiman, Sept. 6, 2016, https://www.sightline.org/2016/09/06/how-seattle-killed-micro-housing.

- Oregon Legislative Assembly, House Bill 3395, H.B. 3395 (2023), https://olis.oregonlegislature.gov/liz/2023R1/Downloads/MeasureDocument/HB3395/Enrolled.

- Hawaii Legislature, A Bill for an Act Relating to Housing, H.B. 2090 (2024), https://legiscan.com/HI/text/HB2090/id/2975587/Hawaii-2024-HB2090-Amended.html.

- Montana Legislature, Montana Land Use Planning Act, S.B. 0382 (2023), https://archive.legmt.gov/bills/2023/billpdf/SB0382.pdf.

- Nicholas Kristof, “The Old New Way to Provide Cheap Housing,” The New York Times, Dec. 9, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/09/opinion/homelessness-housing-shortage.html.

- “American Homeowners Are Wasting More Space Than Ever Before,” Diana Olick, Dec. 18, 2024, https://www.cnbc.com/2024/12/18/american-homeowners-are-wasting-more-space-than-ever-before.html.

- “New Laws Open Doors to Affordable Shared Housing Arrangements,” Kery Murakami and Gabriel Kravitz, Dec. 4, 2024, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2024/12/04/new-laws-open-doors-to-affordable-shared-housing-arrangements.

- Aaron M. Renn and Alex Armlovich, “Microunits: A Tool to Promote Affordable Housing,” Manhattan Institute, 2016, https://manhattan.institute/article/microunits-a-tool-to-promote-affordable-housing.

- Aaron M. Renn and Alex Armlovich, “Microunits: A Tool to Promote Affordable Housing.”

- “Converting Offices to Tiny Apartments Could Add Low-Cost Housing,” Alex Horowitz and Tushar Kansal, Feb. 4, 2025, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2025/02/04/converting-offices-to-tiny-apartments-could-add-low-cost-housing.

- “Co-Living Could Unlock Office-to-Residential Conversions,” Alex Horowitz and Tushar Kansal, Oct. 22, 2024, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2024/10/22/co-living-could-unlock-office-to-residential-conversions.

- “The Gap: A Shortage of Affordable Homes,” National Low Income Housing Coalition, https://nlihc.org/gap.

- N.L.I.H. Coalition, The Gap: A Shortage of Affordable Homes, accessed 2024, https://nlihc.org/gap.

- “The Gap: A Shortage of Affordable Homes,” National Low Income Housing Coalition.

- Mihir Zaveri, “New York Wants to Pay Landlords to Fix and Rent Single-Room Apartments,” The New York Times, Dec. 12, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/12/nyregion/new-york-sro-apartments.html.

- “City of Yes for Housing Opportunity,” https://www.nyc.gov/content/planning/pages/our-work/plans/citywide/city-of-yes-housing-opportunity.