As Risks Grow, More States Analyze Fiscal Outlooks

Long-term budget assessments and stress tests provide valuable insights

Earlier this year, legislative staff in Colorado offered lawmakers a blunt, bold warning: “The budget appears to be on an unsustainable path.” Unless the state cut spending or increased revenue, staff members of the Joint Budget Committee (JBC) cautioned in February, ongoing deficits would exhaust the state’s reserves over the next five years. And, if Colorado faced a recession, their memorandum explained, the situation would be even worse.

The JBC analysis shows how, by understanding their long-term fiscal outlooks, state leaders can draw critical conclusions to inform key budget decisions. As in Colorado, policymakers nationwide are increasingly asking for analyses, including long-term budget assessments and budget stress tests—two key tools that can provide such insights.

This increased focus on long-term fiscal health comes at a critical time. More states have faced deficits in recent months, and risks to budget balance—a teetering economy, looming federal cuts, and states’ own decisions to cut taxes and increase spending—abound. By using long-term assessments and stress tests, states are preparing for these risks, building needed reserves, and closing budget deficits, which in most cases they must do by law.

More states using budget analyses

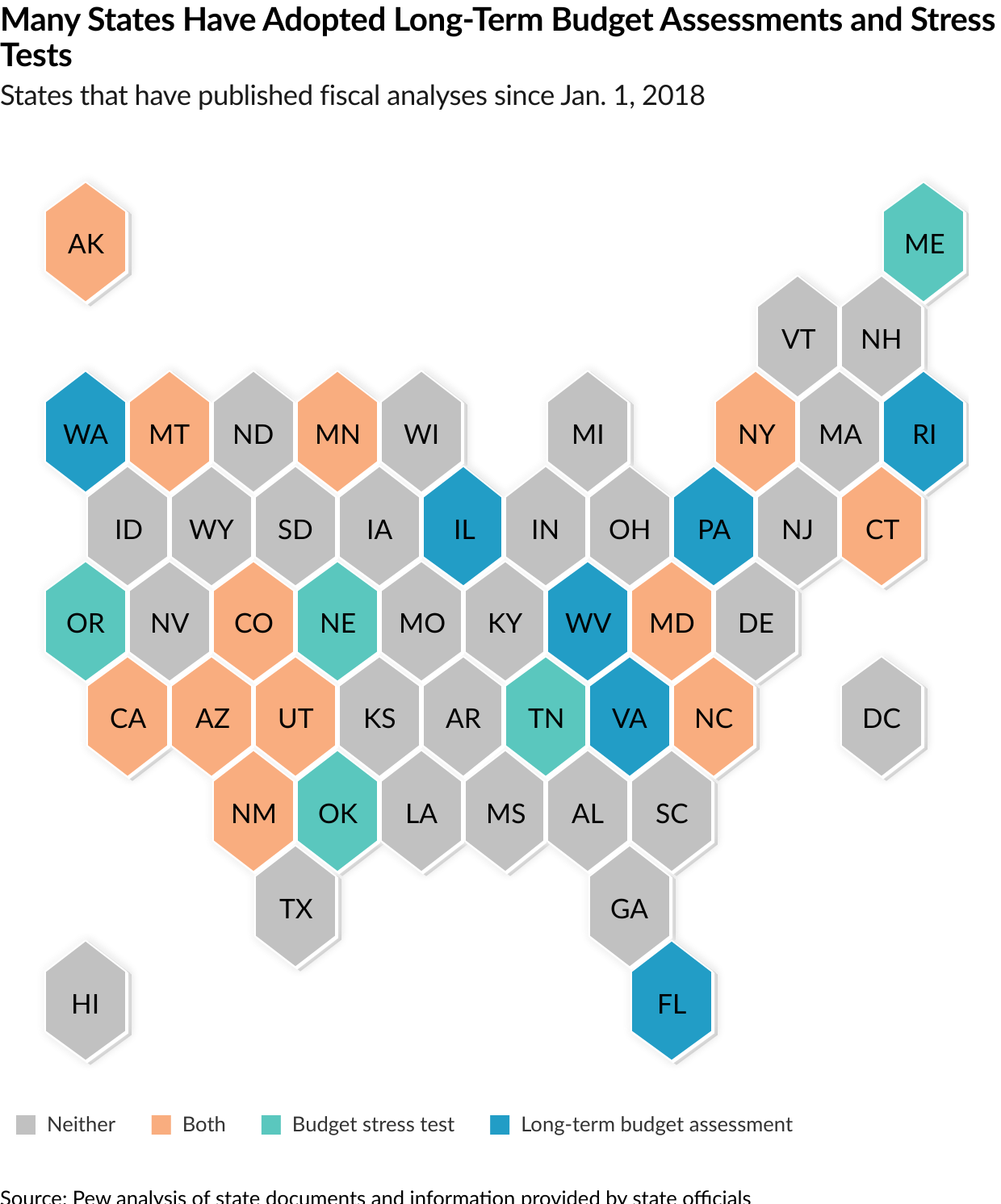

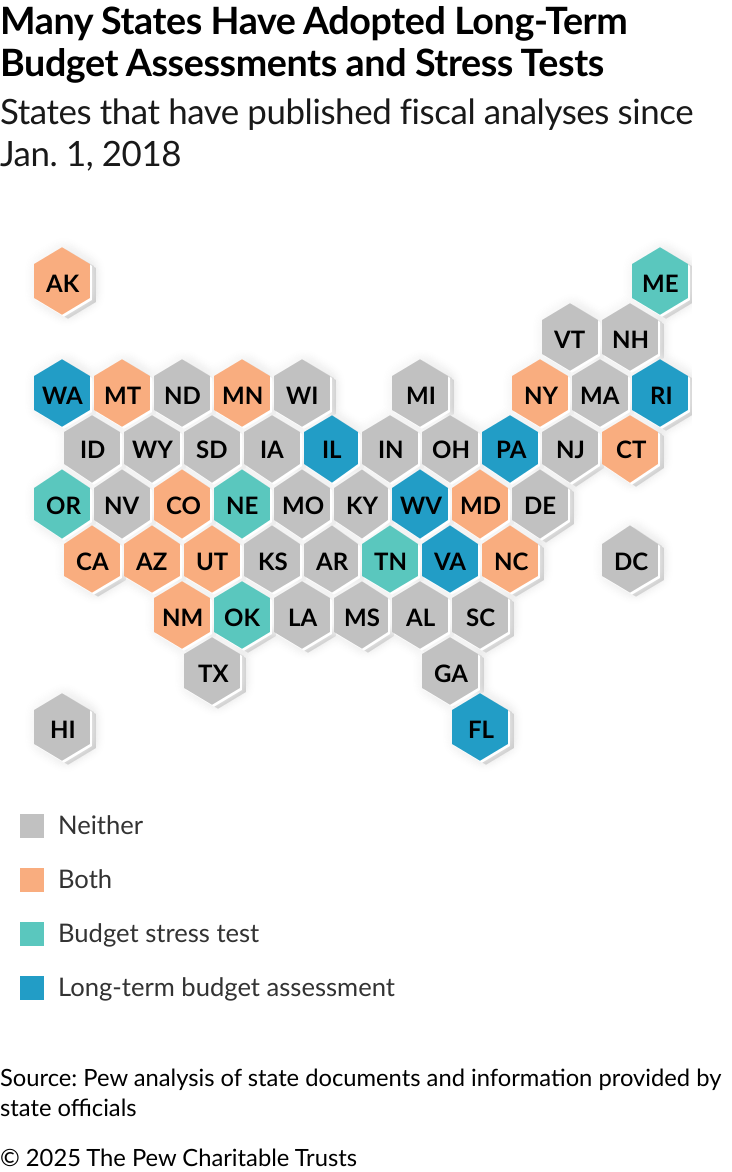

In a November 2023 report, The Pew Charitable Trusts found that since Jan. 1, 2018, 15 states had published long-term budget assessments and 14 had published budget stress tests. To help states determine whether they face potential structural budget deficits, the long-term assessments project revenue and spending at least three fiscal years into the future. They use these projections to evaluate whether the budget is likely to remain balanced and why—or why not. Budget stress tests help policymakers judge whether they are prepared for a recession by estimating the size of budget shortfalls under one or more downturn scenarios. They then can gauge whether the state has sufficient reserves or other contingencies to close potential shortfalls.

More states are recognizing the value of these analyses. Since Pew’s 2023 report, at least four additional ones have published their first long-term assessments (Minnesota, North Carolina, Virginia, and Washington) and at least three have published their first stress tests (Arizona, Oklahoma, and Oregon).

In total, states have published more than 50 long-term budget assessments and budget stress tests in the past 18 months, as states that had already used one or both tools have published new editions to provide updated information. (Pew has compiled these analyses in a sortable database.) Still, roughly half of states have produced neither of these analytic tools over the past seven-plus years.

At least three states—Connecticut, Colorado, and West Virginia—that had stopped publishing one or both of these analyses in recent years reintroduced the tools as they developed their fiscal year 2026 budgets. In February, West Virginia produced its first long-term budget assessment since 2020 at the behest of newly elected Governor Patrick Morrisey (R). The analysis revealed the seriousness of the state’s fiscal problems. When sharing the findings in his State of the State address, Morrisey described West Virginia as facing a “deep structural deficit” that “was papered over with one-time money that’s now running out.”

States benefit from improved analyses

States are not just producing more long-term budget assessments and budget stress tests; they’re also producing better ones. Many have refined their methodologies to generate more rigorous analyses and clearer, better-supported conclusions.

For example, the California Legislative Analyst’s Office’s (LAO) April 2025 stress test proved notable, even from an office that has produced these analyses for years. Most stress tests examine one or two recession scenarios, but LAO conducted thousands of budget simulations, looking forward 50 years.

This approach allowed the office to draw conclusions about how large the state’s reserves need to be to temper the boom-and-bust cycles that have long plagued the state’s budget. Each simulation provided a long enough time horizon to see whether the state could avoid tax hikes and service cuts through multiple ups and downs of the state economy. LAO’s conclusion: California needs much bigger savings.

Like California, Utah is a longtime leader in budget analysis but still looking to improve. The state’s December 2024 long-term budget assessment offered vastly more detail than previous versions. For instance, it specified and described factors that are likely to affect the budget over the next five years—including changing demographics, federal policies, and state tax cuts. The Utah Legislature also amended the state’s stress test requirement in 2024 to include expanded analysis of risks to the state’s Medicaid program, a timely addition given the growing costs of these programs and ongoing federal funding uncertainty.

Informing policymaker decisions

As most states’ 2025 legislative sessions wind down throughout the country, the long-term budget assessments and budget stress tests are demonstrating their worth. Several states, such as Minnesota, New Mexico, and North Carolina, routinely use stress tests to set reserve levels. In others, including Connecticut, new analyses are spurring discussion of the states’ recession vulnerability and the appropriate size of savings.

Long-term budget assessments are proving valuable even—or perhaps especially—when they deliver bad news. By showing the size of long-term deficits, assessments in states such as Alaska, Illinois, Maryland, North Carolina, New York, and Pennsylvania have shown lawmakers the magnitude of adjustments—either in the form of increased revenue or reduced spending—that they must adopt to bring their budgets into balance.

Of course, having this information does not make lawmakers’ decisions quick, easy, or uncontroversial. In North Carolina’s long-term budget assessment, for example, the executive budget office found multibillion-dollar future deficits, a sharp reversal from the state’s recent surpluses.

“The truth is,” said Governor Josh Stein (D), who attributed the deficits to recent tax cuts, “ we are in for some self-inflicted fiscal pain.”

But understanding the size of the problem is still the first step to solving it. In Colorado, lawmakers closed a $1.2 billion gap in the budget they adopted this spring. To do so, they protected many core services, but also made some difficult cuts such as delaying a proposal to make inmates’ phone calls free and ending universal free school meals unless voters approve new funding. Thanks in part to the JBC’s long-term analysis, Colorado lawmakers recognize that, even with these decisions, they have more work to do to get the budget back on a sustainable path.

As Colorado state Senator Barbara Kirkmeyer (R), a JBC member, told Colorado Newsline, a nonprofit online news organization: “You don’t get out of a structural deficit in a one-year budget.”

Josh Goodman works on The Pew Charitable Trusts’ state fiscal policy project. Former Pew staff member Carolyn Ellison contributed to this analysis.