Federal Saver’s Match, Coming in 2027, Could Boost Automated Retirement Savings Programs

New incentive could lift participation in—and contributions to—auto-IRA programs

Overview

Nearly 57 million American workers—almost half of the private sector workforce—don’t receive retirement benefits at their workplaces.1 That lack of access affects their ability to save and plan for their financial future, including retirement. It also affects taxpayers: A comprehensive study by The Pew Charitable Trusts estimated the cost of insufficient retirement savings to federal and state governments over a 20-year period to be $1.3 trillion.2 A lack of retirement savings results in decreased household spending and increased demand for social assistance programs—which, in turn, places a greater burden on a shrinking tax base.

To address this retirement savings gap, 17 states have enacted laws to establish automated individual retirement accounts (auto-IRAs). Under these plans, employers help workers to save for retirement through automatic payroll deductions that are deposited into an IRA managed by a state-approved financial services firm. These state-facilitated auto-IRAs have emerged as an indispensable tool for workers who lack access to employer-sponsored retirement plans, enabling them to save regularly through payroll contributions, much as employees at larger companies save through 401(k) plans. Unlike 401(k)s, however, auto-IRAs are not eligible for employer contributions, which means that employees have less incentive to participate than they would if there were an employer match.

But a new federal plan has the potential to change that dynamic.

A recent survey by The Pew Charitable Trusts of workers who do not have access to employer-sponsored retirement benefit plans found that a new federal retirement savings incentive known as the Saver’s Match, which is set to take effect in 2027, could significantly increase participation in state auto-IRA programs. The survey also found that eligible workers are likely to increase their voluntary contributions with Saver’s Match in place, enhancing their overall savings.

Under the Saver’s Match program, the federal government will make a matching 50% contribution to eligible workers’ auto-IRAs. The match—as much as $1,000 for individuals and $2,000 for couples—would come in the form of a federal tax credit deposited directly by the U.S. Treasury into participants’ retirement accounts. To be eligible for a full or partial match, individuals must earn less than $35,500; for couples, the limit is $71,000.

Saver’s Match could enhance the retirement savings of millions of low- and moderate-income households. This greater opportunity for workers to save for retirement would help them secure their futures, and also ease burdens on state budgets as lawmakers face the demands of an aging population.

Because retirement wealth-building opportunities are often tied to income and access to employer-provided plans, the Saver’s Match coupled with auto-IRAs could prove particularly valuable for workers with limited access to traditional retirement savings vehicles. Research consistently shows that fewer Black and Hispanic workers have access to employer-sponsored retirement plans compared with their White counterparts. For example, a previous Pew analysis of full-time private sector workers found that 63% of White, non-Hispanic workers reported having access to a retirement plan, compared with 56% of Black, non-Hispanic workers and 38% of Hispanic workers.3

Employers in some industries, such as hospitality, agriculture, and the service sector, also tend to offer fewer retirement benefits than do employers in other industries. And workers in those industries are disproportionately Black and Hispanic, resulting in less access to work-based retirement savings opportunities and lower participation rates than in other industries. Additionally, income disparities contribute to lower retirement savings over time, as some households simply have less money available to save than other households. The federal Saver’s Match, in conjunction with state auto-IRAs, can address those disparities by providing a structured, accessible savings mechanism that benefits low- to moderate-income workers.

To assess interest in the Saver’s Match, Pew surveyed more than 1,000 people who don’t have access to an employer-sponsored retirement plan such as a 401(k). The survey found that 87% of all respondents were more likely to save in an auto-IRA program with the addition of the Saver’s Match.

Among the survey’s other key findings:

- There’s enormous interest in automated savings programs among all types of workers. Initially, 84% of respondents said they were likely to participate in an auto-IRA program. This number grew to 94% when they were informed of the Saver’s Match.

- The Saver’s Match increased respondents’ interest in the concept of an auto-IRA, even when they weren’t interested at first. Among the 16% of respondents who initially said they weren’t likely to participate in an auto-IRA program, 52% showed increased interest after learning about the Saver’s Match.

- The Saver’s Match concept prompted respondents to say they wanted to save more, with 79% of all respondents indicating that they would increase their contributions under the program—including 80% of those who were initially likely to participate and 73% of those who were initially unlikely to participate.

These trends were consistent across demographic groups, including race and ethnicity, age, education, income, and employment status (with some statistically insignificant variations in magnitude). While self-reported intentions may not perfectly predict actual behavior, the strong positive shift across groups suggests that the Saver’s Match could be a powerful policy lever for increasing both participation in and contributions to auto-IRA programs.

The survey results indicate that the Saver’s Match, if implemented effectively, could be a valuable policy tool for boosting retirement savings, particularly among those who are already predisposed to participate in an auto-IRA program. The responses also show the potential to engage individuals who are initially hesitant about participation. Given these findings, it is essential that policymakers make the Saver’s Match easily available to auto-IRA participants in order to maximize the effectiveness of such programs in reducing the retirement savings gap in the United States.

Realizing these potential benefits, however, will require addressing several technical and operational barriers. Most participants in state-sponsored auto-IRAs contribute to Roth IRAs (which are funded with after-tax dollars, allowing for tax-free withdrawals in retirement). However, Saver’s Match funds can be deposited only into qualified pre-tax retirement accounts such as a traditional IRA or traditional 401(k), which differ from a Roth account because they are taxed on withdrawal. Additionally, many eligible auto-IRA participants may not have a federal tax liability and may not file a federal tax return, making them unable to claim the match.

To maximize the impact of both the Saver’s Match and auto-IRA programs, federal policymakers should take the following steps as they prepare to launch the Saver’s Match4:

- Automate as much as possible: Existing and new tax forms (if any are needed) should be pre-populated with information already collected (from W-2s, 1099s, and Form 5498, for example). A taxpayer’s eligibility for the program and the match amounts should be automatically calculated. The goal is to develop a streamlined claiming process with minimal burden on taxpayers.

- Simplify the claiming process: Tax forms should contain clear instructions and effective visual and textual cues in an effort to minimize any potential complexities and remove the need for claimants to do manual calculations. Policymakers should consider adding account information to existing tax forms rather than requiring new ones.

- Provide options for people who don’t have to file a federal tax return: A simple claiming process should be created for people who contribute to an auto-IRA but have no federal tax liability and fall below the Form 1040 filing threshold, similar to procedures for the IRS’ nonfiler sign-up tool.

- Establish robust systems: Policymakers should develop procedures for handling Saver’s Match contributions and any associated errors, inconsistences, or suspected fraud, similar to existing tax refund procedures. Additionally, if a Saver’s Match contribution can’t be completed because of an error or lack of account information, a default process should be in place to protect the individual’s eligibility to claim the match.

- Develop clear, timely, multichannel communication: The Treasury Department and IRS should work with key stakeholders (tax preparers, employers, payroll companies, record keepers, community groups, and state auto-IRA programs) to promote awareness of the Saver’s Match program, simplify processes, and maximize participation.

Implementing these recommendations would help ensure that the strong interest in the Saver’s Match demonstrated by Pew’s survey translates into actual increased retirement savings for workers who need it most.

Initial intent to participate in auto-IRAs

From April to May 2024, Pew fielded a nationwide survey of 1,130 individual workers who didn’t have access to an employer-sponsored retirement savings plan at work and didn’t participate in an auto-IRA. Respondents were given a description of a generic auto-IRA program. The description asked respondents to imagine their state government offering them the opportunity to participate in an auto-IRA program that would require their employer to automatically deposit part of each paycheck into a retirement account controlled by the respondent, with a private financial services company managing the account and the state providing oversight. The description made clear that the account would stay with respondents if they changed jobs.

What Are Automated Individual Retirement Accounts (Auto-IRAs)?

Auto-IRAs are state-facilitated retirement savings programs designed to address a gap in access to retirement savings for millions of American workers. These programs:

- Automatically enroll eligible employees in individual retirement accounts (IRAs).

- Provide retirement savings to workers who don’t have access to employer-sponsored plans.

- Allow workers to opt out or change contribution levels at any time.

- Collect contributions through automatic payroll deductions.

- Use post-tax Roth IRAs as the default account type, but traditional IRAs are also available.

- Minimize administrative burdens on employers, requiring only a one-time registration of employees and the facilitation of employee contributions through the payroll process, which employers already manage.

Auto-IRAs seek to make wealth-building easier and more accessible, particularly for those who work in small businesses or industries that traditionally lack retirement benefits.

The description of this hypothetical auto-IRA program included some additional details that are similar to those seen in many existing state auto-IRA plans:

- By default, 5% of the respondent’s pay would be deducted and deposited into an IRA owned by the respondent.

- Respondents could change their contribution amount or leave or rejoin the program at any time.

- Employers would not make any additional contributions on behalf of the respondent.

- By default, the program would invest the contributions in a fund with a mix of assets (e.g., stocks and bonds) appropriate for someone of the respondent’s age, but respondents would have other options as well.

- Respondents were told that because they would have already paid taxes on contributions to the auto-IRA, the principal could be withdrawn at any time without penalty. And growth in the account would be tax-free if withdrawn at retirement.

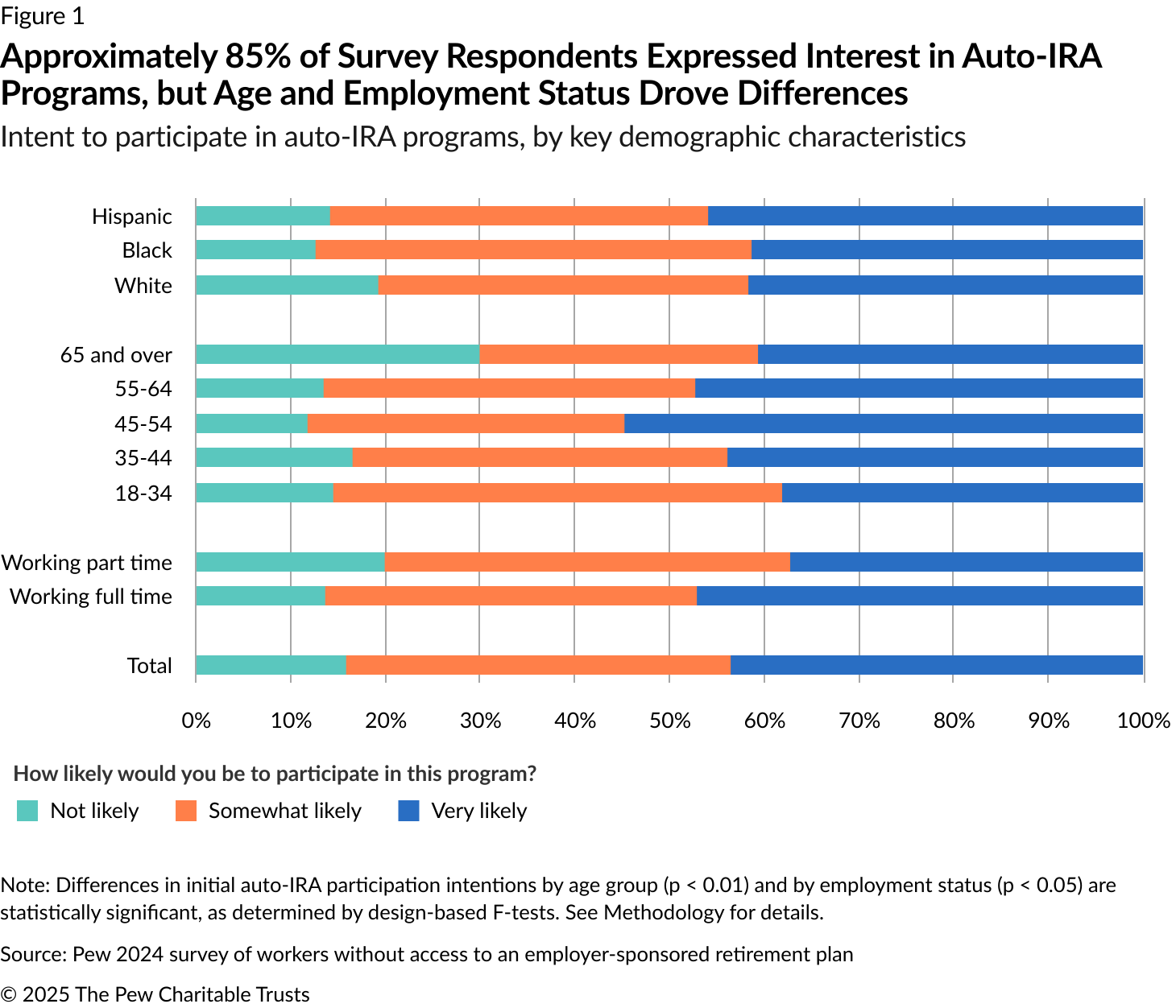

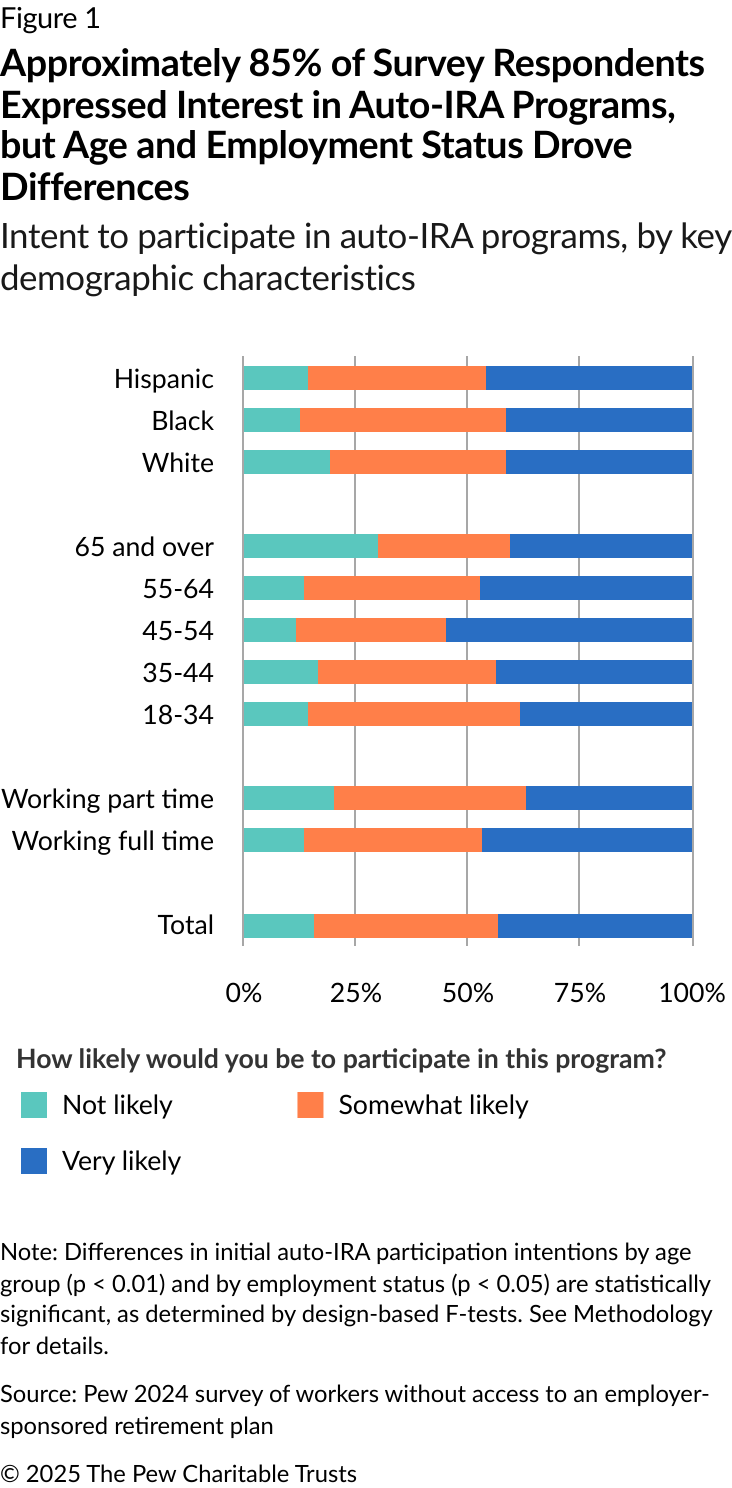

A large majority of survey respondents were initially inclined to participate in the hypothetical auto-IRA program. Approximately 85% indicated they were very likely (44%) or somewhat likely (41%) to participate. Only 16% said they were not likely to participate.

Statistical significance measures the likelihood that any difference between groups is due to chance. There were no statistically significant differences by gender, race, household income, or education, implying a fairly uniform desire to participate by respondents across all of these demographics.

Unsurprisingly, there were statistically significant differences in the likelihood of participation that varied depending on the respondent’s age. Individuals ages 18 to 64 all expressed extremely strong participation interest (83%-88%) but there was a marked decrease in likelihood of participation among those age 65 and older (70%). This pattern is consistent with the fact that older individuals are closer to retirement than younger people, have shorter saving and investing time horizons, and may have different financial goals and motivations for working.

There were also statistically significant differences between how full- and part-time workers responded to the hypothetical auto-IRA program. Individuals who worked full time showed a markedly higher level of strong interest (47% “very likely”) compared with those who worked part time (37% “very likely”). And fewer full-time workers said they were not likely to participate at all (14%, versus 20% of part-time workers). Again, however, overall interest was high in both groups, with 86% of full-time and 80% of part-time workers saying they were “very” or “somewhat” likely to participate in an auto-IRA if offered the opportunity.

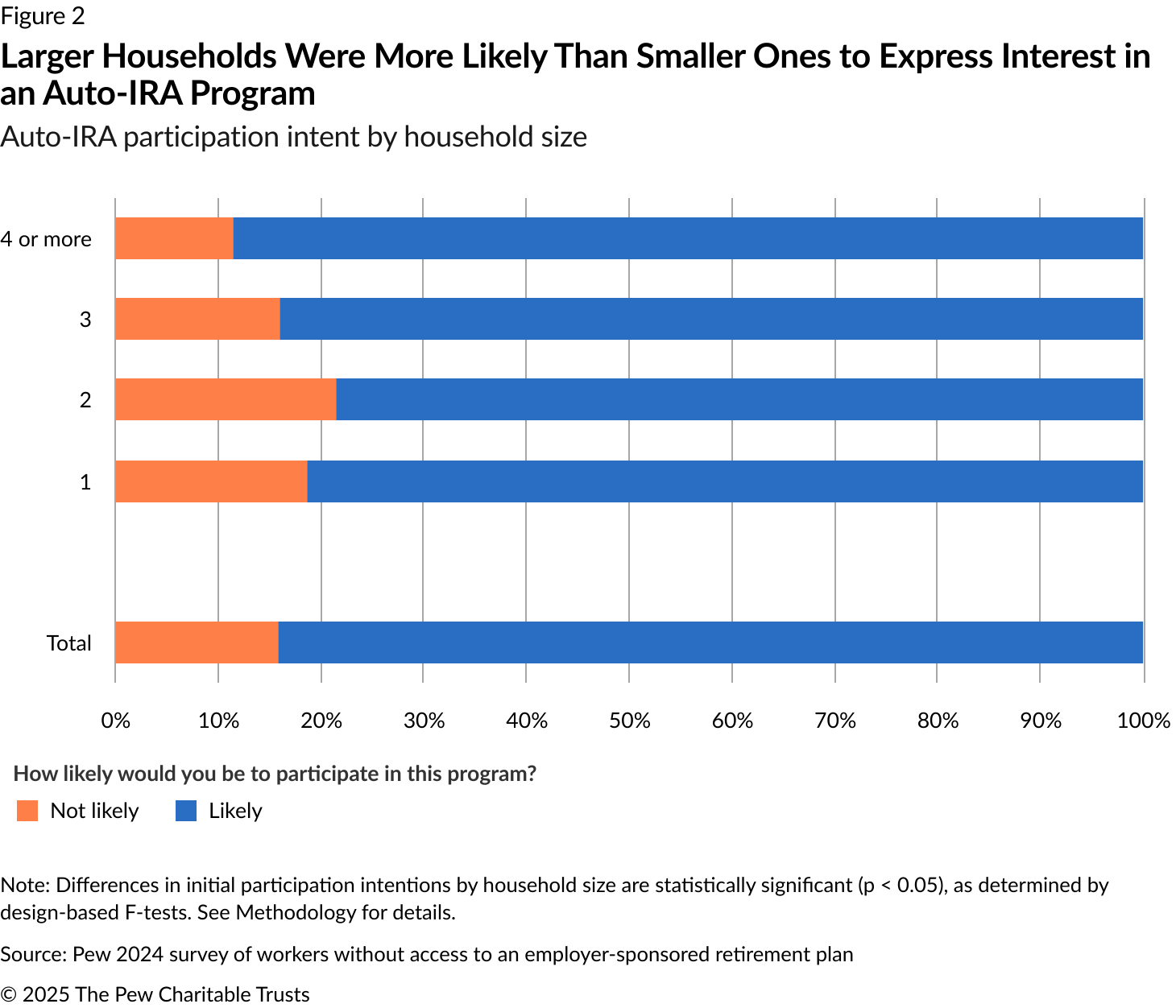

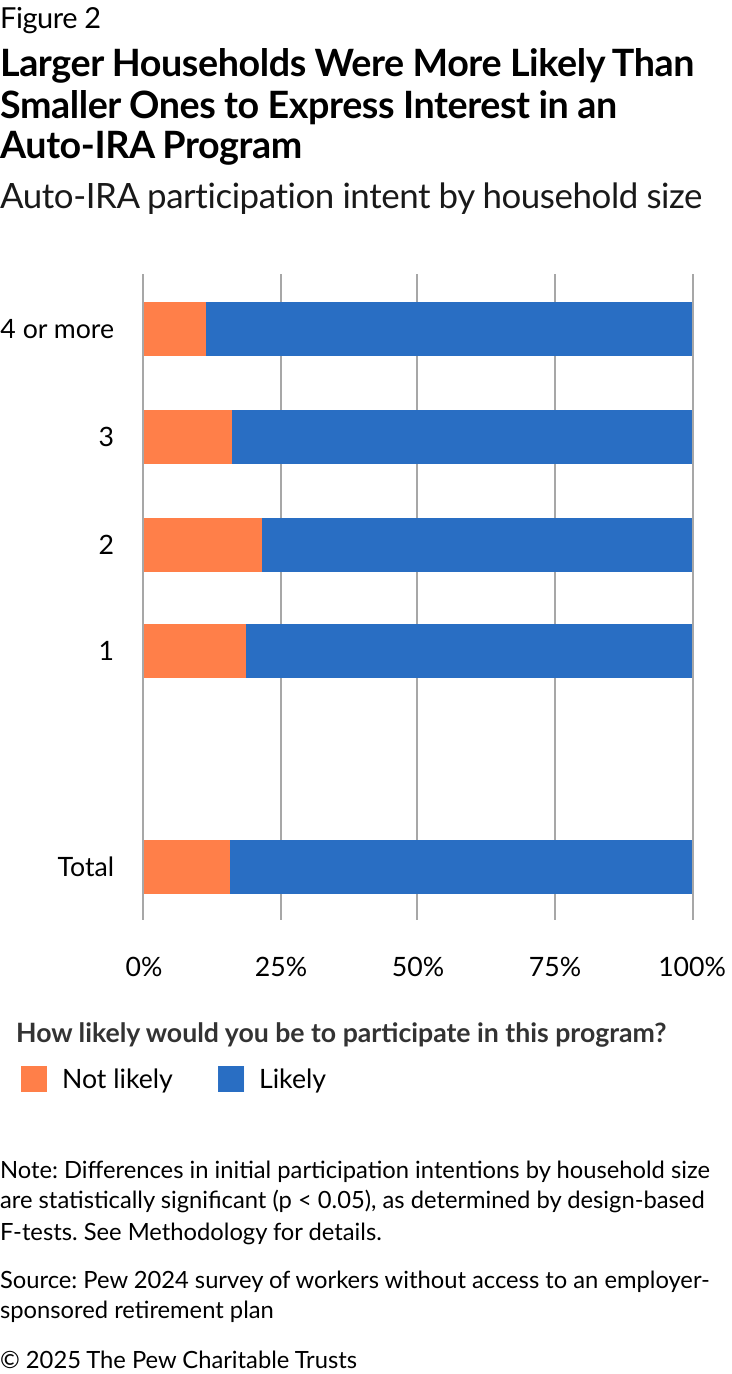

There were statistically significant differences in survey responses across household sizes, with larger households more likely to express stronger interest in participating in an auto-IRA program. Households with four or more members had the highest level of interest in participating (89%), while one- and two-person households showed the lowest (81% and 79%, respectively). However, intent to participate was high across all groups.

The high overall intention to participate in an auto-IRA program is a positive indicator for the potential adoption of such programs nationwide. It suggests that there is a widespread recognition of the need for retirement savings among the overall population. This high baseline also sets the stage for understanding how the addition of the Saver’s Match might further increase participation and contribution levels, which subsequent sections of this report explore.

Impact of the Saver’s Match on auto-IRA participation

The Saver’s Match

The Saver’s Match is a new retirement savings incentive designed to encourage low- and moderate-income individuals to save for retirement. It will be available to those who meet eligibility requirements, even if they have no federal tax liability. The match:

- Was introduced as part of the SECURE 2.0 Act of 2022 and becomes available in 2027.

- Replaces the existing Saver’s Credit, which enables taxpayers to reduce their tax burden but offers a very limited benefit to those who owe a small amount of—or no—federal taxes.

- Provides a federal 50% matching contribution, up to $1,000 per single filer and $2,000 for those who are married and filing jointly.

- Is deposited directly into the worker’s eligible retirement account.

- Aims to boost retirement savings for those who need it most: individuals who earn less than $35,500 and couples with income below $71,000.

This provision represents a valuable incentive for savers and has significant implications for wealth building.

Survey respondents were asked next to imagine an additional feature to this hypothetical auto-IRA that would allow them to receive a matching contribution equaling as much as half of what they contributed to their IRA through payroll deductions. This additional money, they were told, would come in the form of a tax credit paid directly into their retirement account. Respondents were asked whether such a feature would make them more likely to participate in an auto-IRA.5

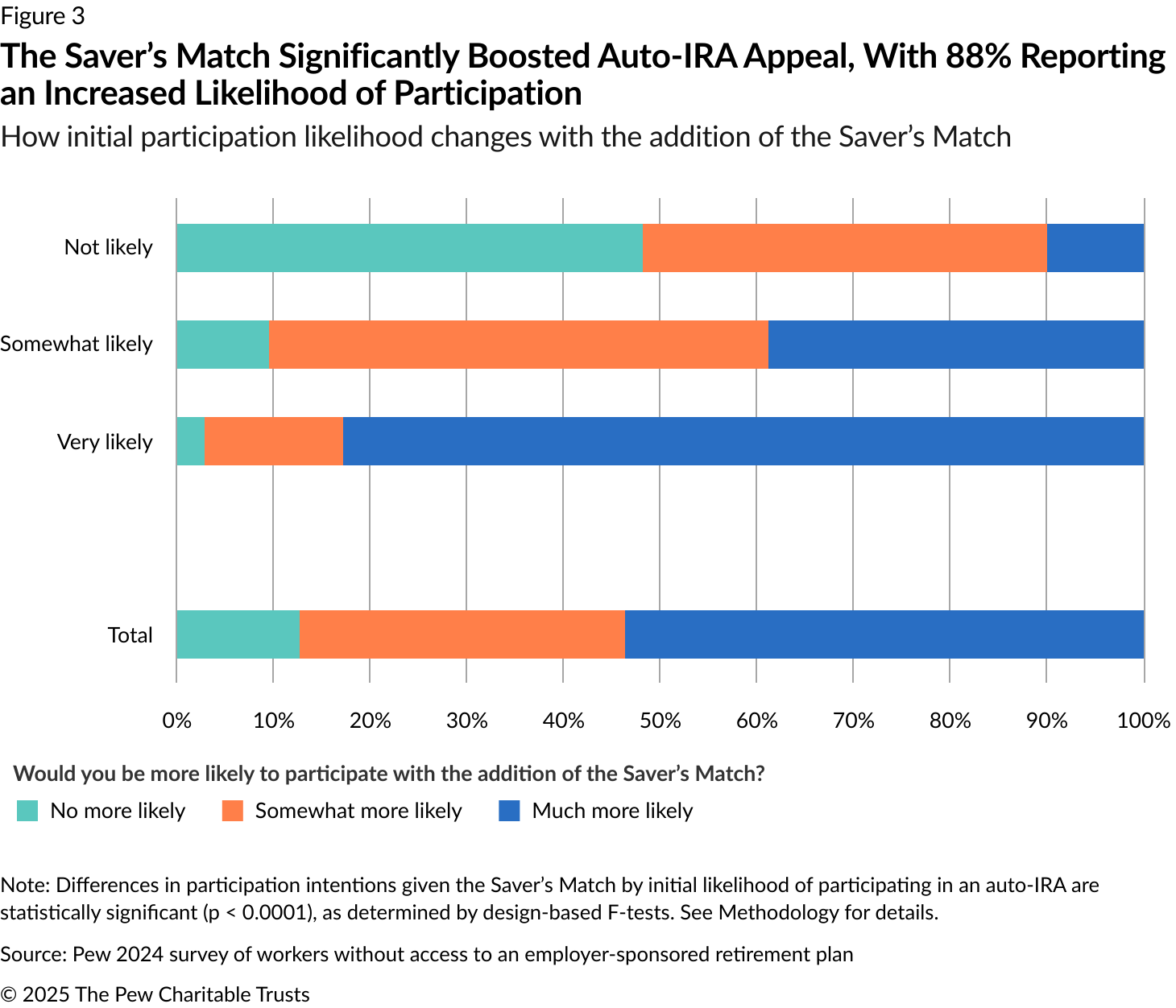

Information about the Saver’s Match had a substantial positive effect on participation likelihood across all groups: those who were initially “very likely” or “somewhat likely” to participate and those who at first were “not likely” to participate in the hypothetical auto-IRA program. (See Figure 3.) But there were some nuanced effects across these groups:

- For respondents who were initially very likely to participate, 83% became much more likely to participate and 14% became somewhat more likely to participate. In total, 97% became even more likely to participate when the Saver’s Match was offered, while only 3% reported no change in their likelihood of participating.

- For respondents who were initially somewhat likely to participate, 39% became much more likely to participate and 52% became somewhat more likely to participate. Only 10% reported no change in their likelihood of participating.

- Finally, for respondents who were initially unlikely to participate, 10% became much more likely to participate and 42% became somewhat more likely to participate, while 48% reported no change in their likelihood to participate, representing a significant shift in intentions for this group.

The effect of the Saver’s Match was positive for all groups, but the impact was unsurprisingly strongest for those who initially were very likely to participate. However, the effect was still very strong for those who were only somewhat likely to participate, with 90% becoming more likely to participate. And the effect of the Saver’s Match was large even among those who were initially not likely to participate, with over half (52%) becoming more likely to participate. The difference in the magnitude of the effect between those who were initially likely and those who were initially not likely was statistically significant, with those who were initially likely to participate becoming even more likely to participate (p < 0.0001). Overall, 87% of all respondents indicated they would be more likely to participate in an auto-IRA program with the Saver’s Match, while only 13% reported no change in their likelihood of participating.

These findings indicate that the Saver’s Match had a strong reinforcing effect on those who were already interested in auto-IRA programs—and a substantial effect on converting initially uninterested individuals. The match appears to be an extremely effective tool for boosting participation intentions across both groups, with its impact particularly pronounced among those already predisposed to participate.

These are reported intentions and may not predict actual behavior. However, the strong positive shift in intentions suggests that the Saver’s Match could be a powerful policy lever for increasing participation in the auto-IRA programs.

Impact of the Saver’s Match on auto-IRA contribution levels

Finally, respondents were asked whether the matching contribution would lead them to consider contributing more each month to their account.

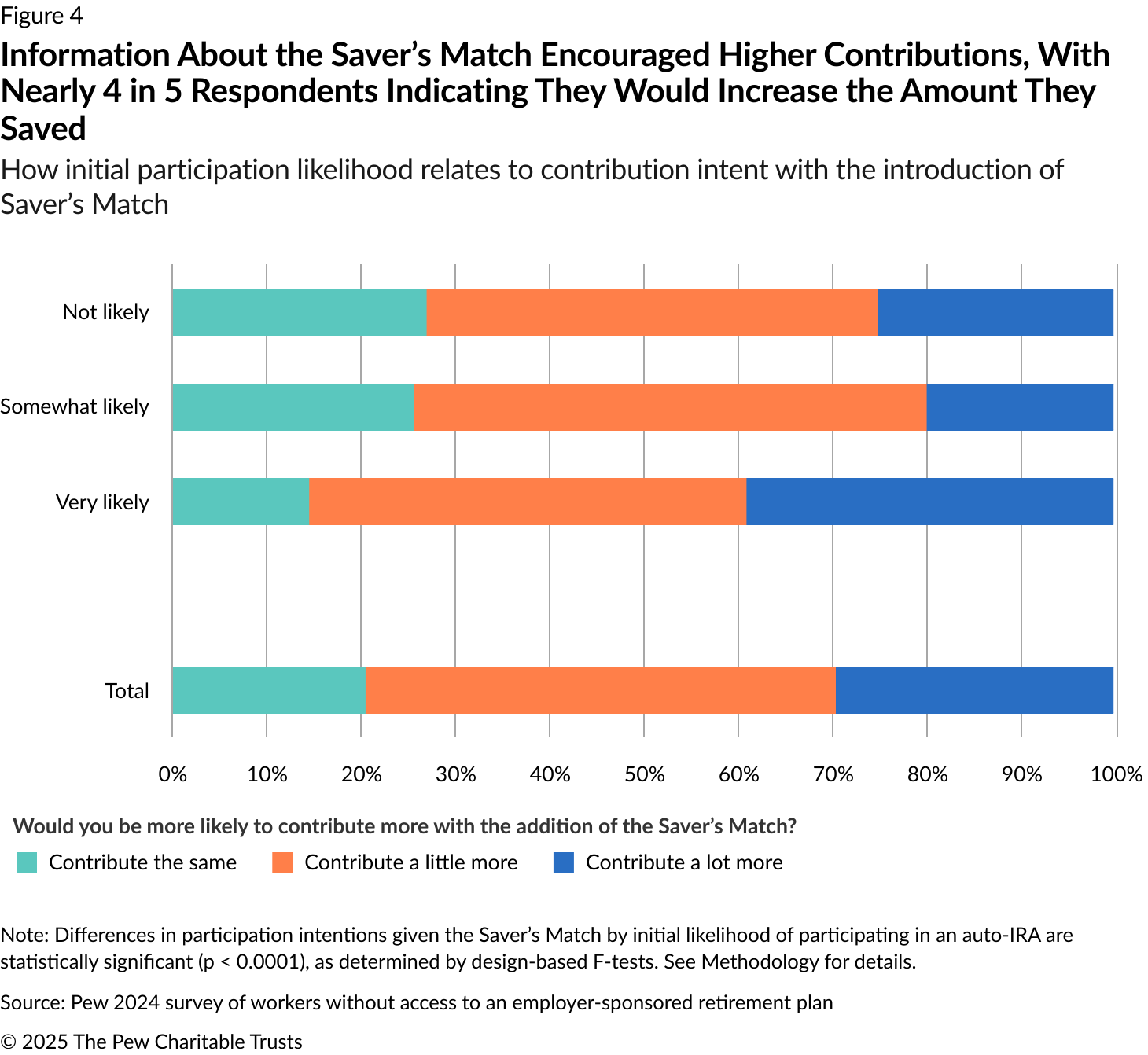

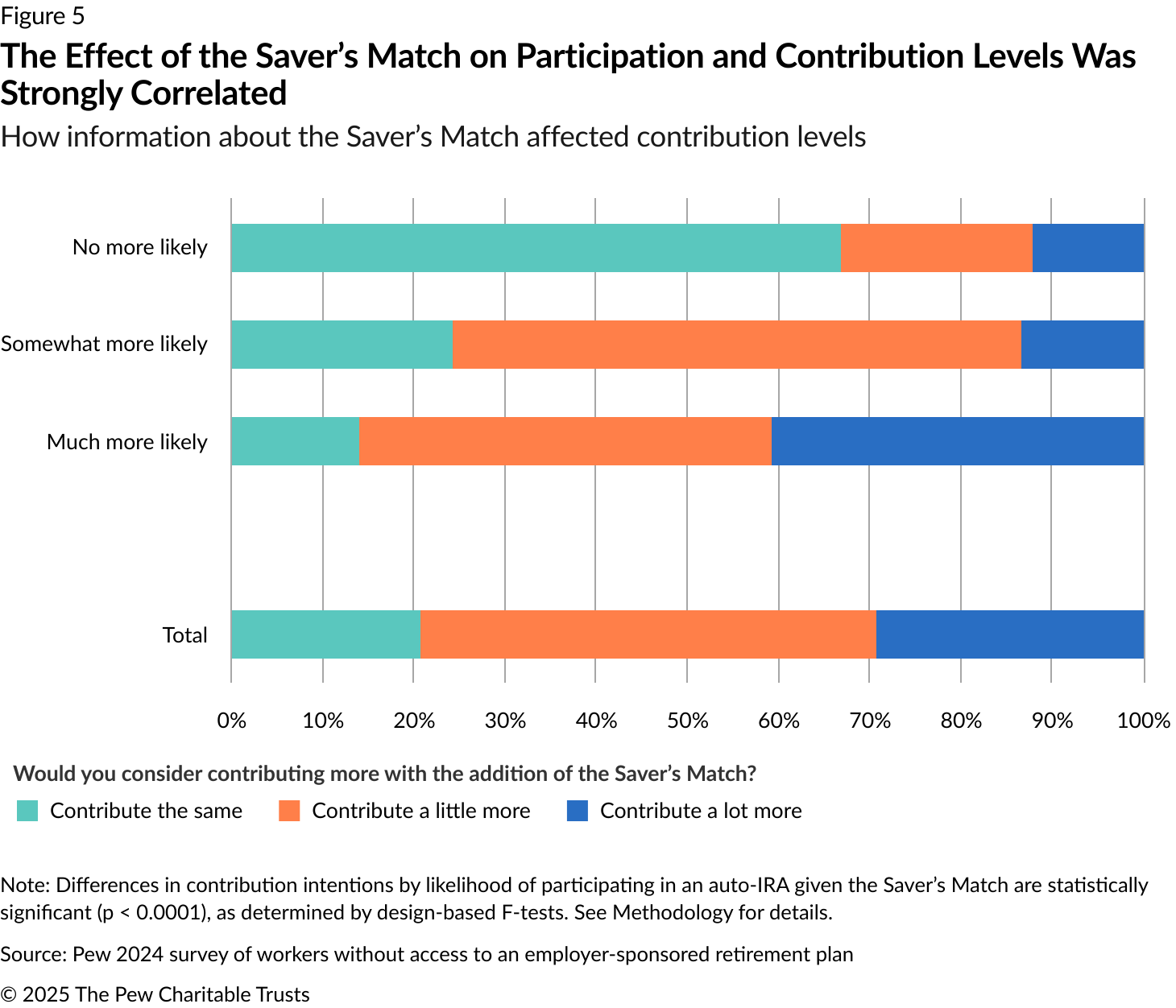

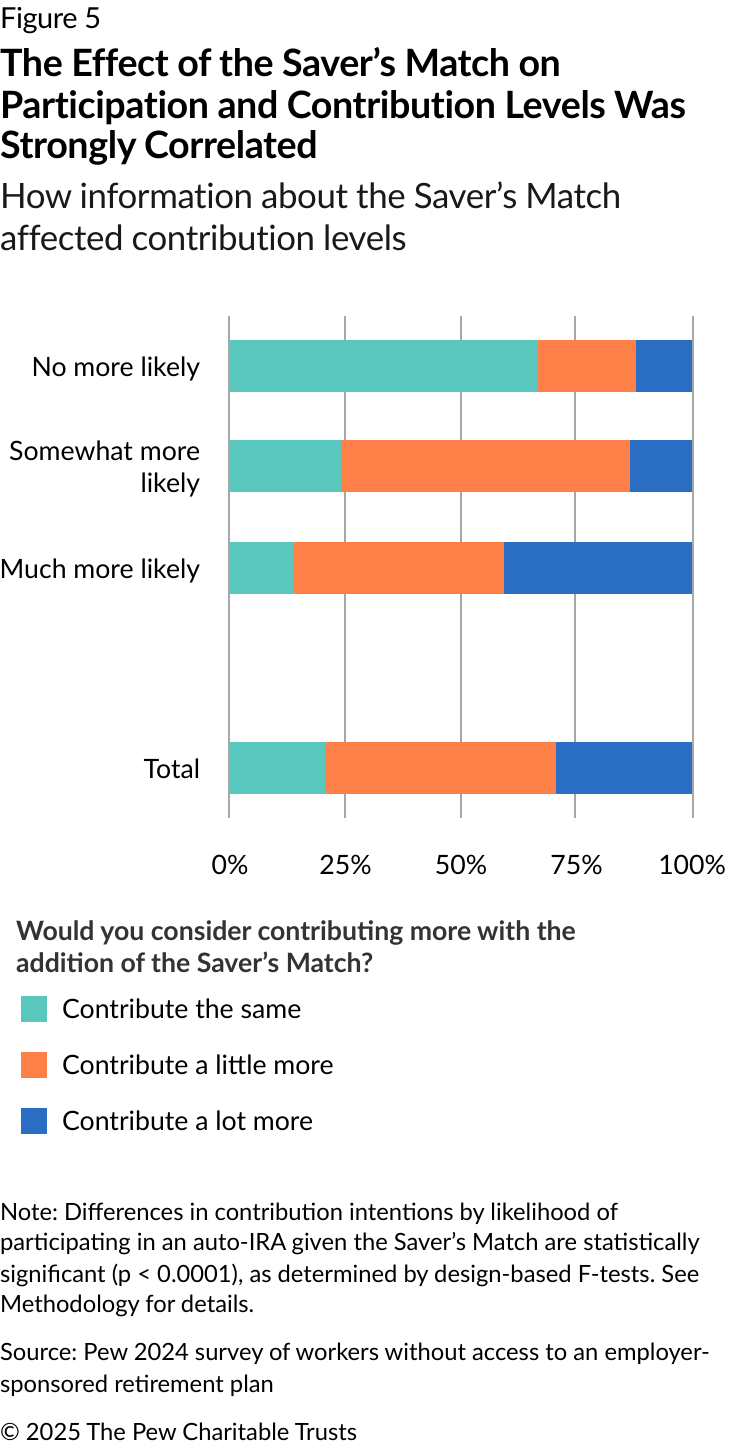

Again, analysis shows that the Saver’s Match not only influences participation intentions but also has a substantial and nuanced impact on intended contribution levels across the different groups:

- For respondents who were initially very likely to participate, 85% indicated they would increase their contributions (39% would increase contributions a lot more and 46% indicated they would contribute a little more with the Saver’s Match). Only 15% of this group reported they would not increase their contributions.

- Of those respondents who were initially somewhat likely to participate, 75% would increase their contributions (20% by a lot more and 55% by a little more), while 26% would contribute the same. Among those who were initially unlikely to participate but became more likely to participate after being told about the Saver’s Match, 73% indicated they would increase their contributions (25% would contribute a lot more and 48% a little more). However, this result should be interpreted with caution because of the relatively small number of initially reluctant respondents who answered the contribution question.

Overall, nearly 4 of 5 respondents reported that the Saver’s Match would motivate them to increase their contributions. The effect was strongest among those who were initially very likely to participate in an auto-IRA program and gradually decreased among those who were less likely to participate. But the positive effect was substantial even among those who were initially less interested.

There was a strong and statistically significant relationship between how the Saver’s Match affected participation likelihood and intended contribution level (p < 0.0001). (Differences with a probability value [p-value] below 0.05 are considered statistically significant.)

- Among those who were much more likely to participate because of the Saver’s Match, 86% indicated that they would increase their contributions (41% a lot more and 45% a little more).

- Those who became somewhat more likely to participate still showed a strong intention to increase contributions, with 76% indicating they would contribute more (13% a lot more and 62% a little more). In contrast, among those who said the Saver’s Match would not make them more likely to participate, only 33% indicated they would increase their contributions, with 67% saying they would not contribute more.

This strong alignment between enthusiasm for participation and the intention to contribute a higher amount with the addition of the Saver’s Match suggests that those most motivated by the match are also the most likely to take fuller advantage of it through higher contributions. Overall, 79% of all respondents indicated they would increase their contributions with the introduction of the Saver’s Match, demonstrating its potentially broad impact on savings behavior.

While these are reported intentions and may not predict actual behavior, the strong positive shift in intended contribution levels suggests that the Saver’s Match could be an effective policy tool for increasing not just participation in auto-IRA programs but also the amount that participants save for retirement.

These findings underscore the potential of the Saver’s Match as a dual-purpose policy lever: It can both increase participation in auto-IRA programs and boost the retirement savings of those who participate, with a particularly strong effect among those already inclined to join such programs.

Effect of demographic differences on the impact of Saver’s Match

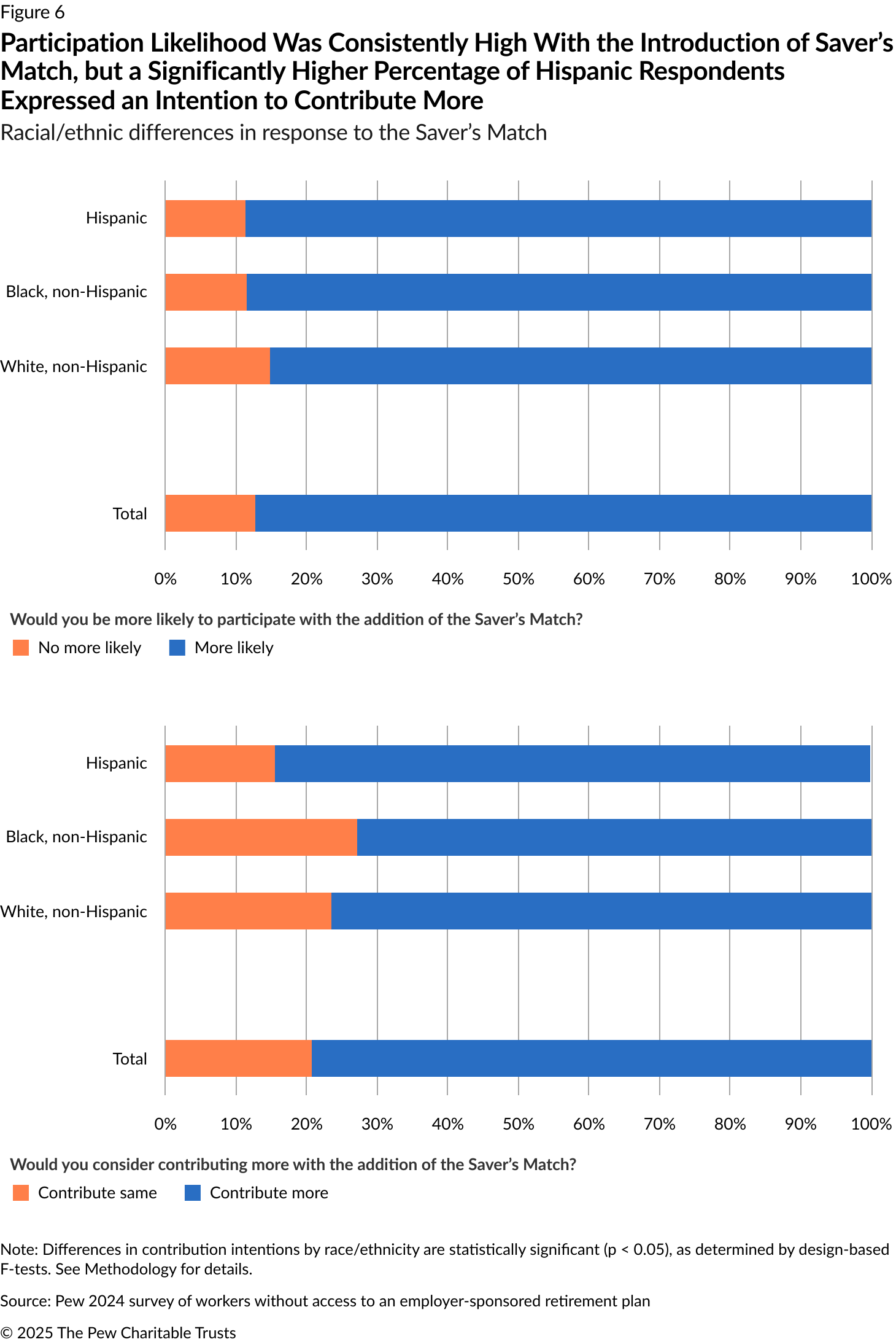

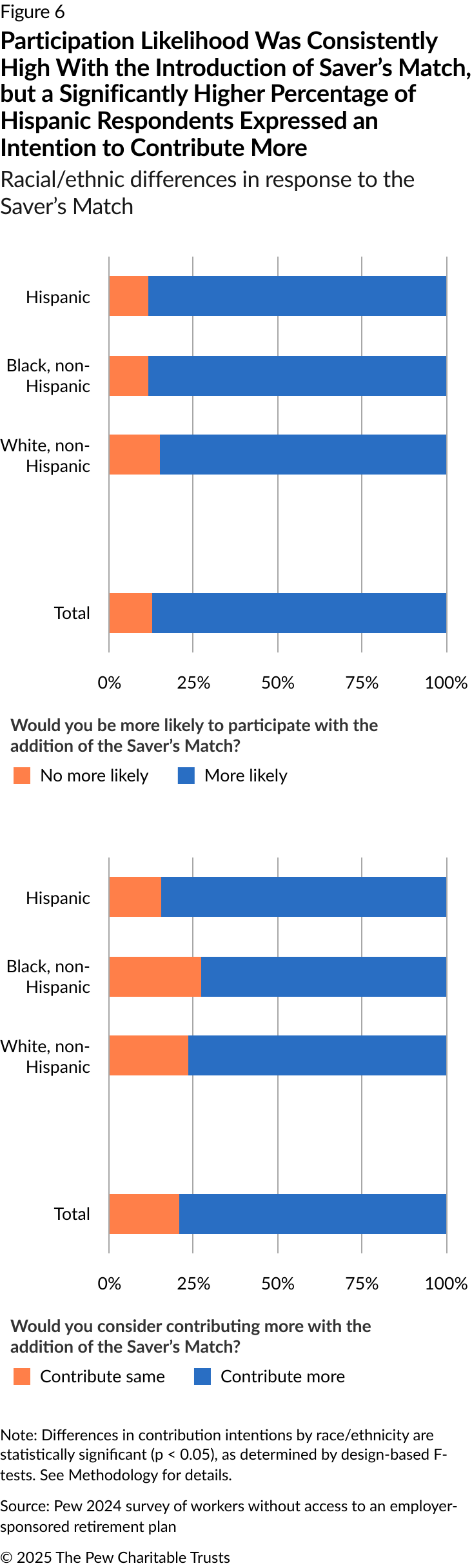

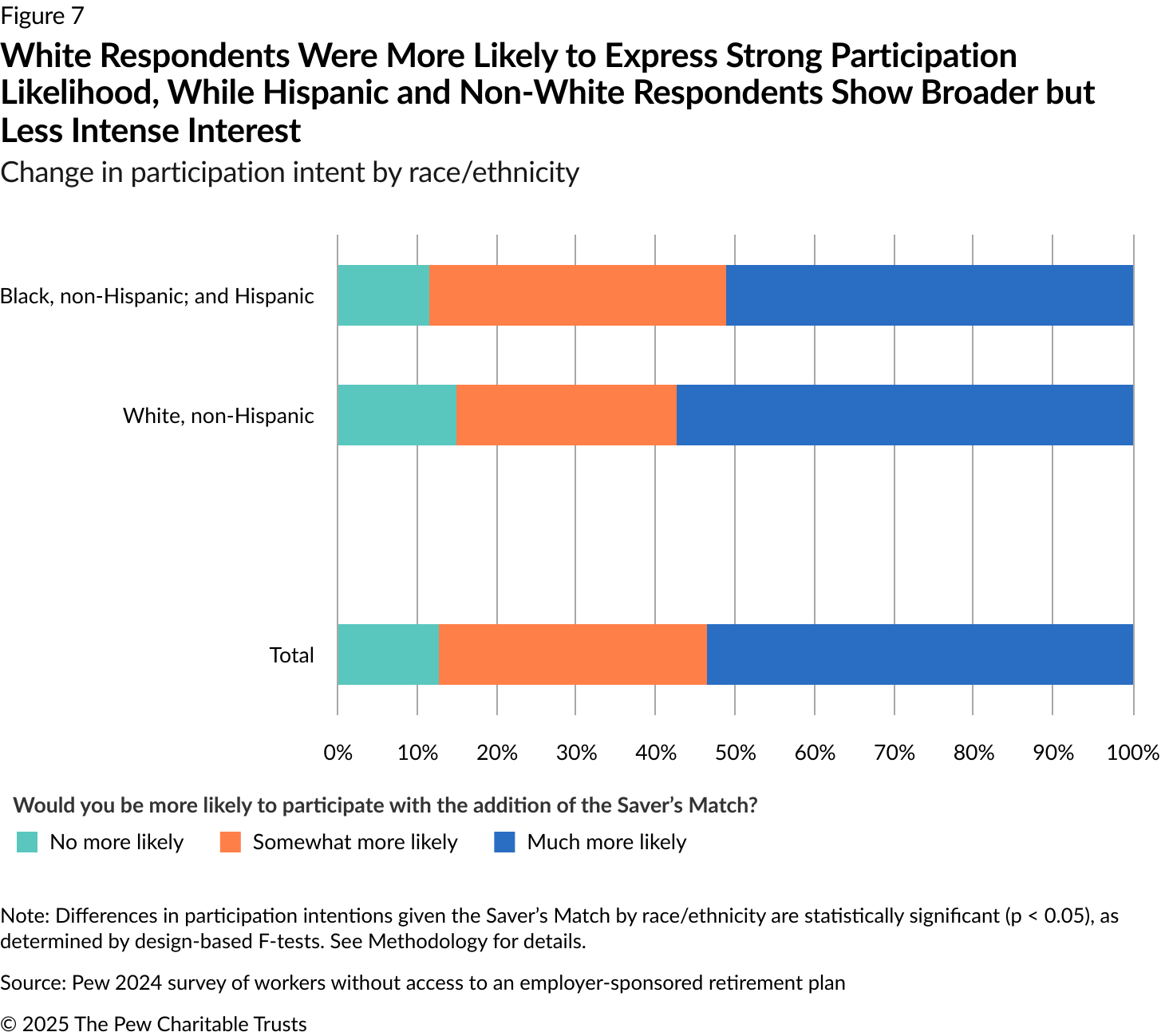

While initial participation intent did not differ significantly by race or ethnicity (Figure 1, above), there were some variations in the effect of the Saver’s Match across different groups.

The Saver’s Match showed a strong positive effect across all racial and ethnic groups. (See Figure 6.) Comparing White, non-Hispanic respondents with all others revealed patterns in how different racial and ethnic groups responded to the Saver’s Match. (See Figure 7.) White, non-Hispanic respondents were more likely than others to report being “much more likely” to participate. However, a larger share of Black, non-Hispanic respondents and Hispanic respondents of any race reported being “somewhat more likely” to participate in an auto-IRA with the addition of the Saver’s Match. These differences in the intensity of response were statistically significant (p = 0.032).

Hispanic respondents showed the greatest intention to increase contributions in the presence of the Saver’s Match, with a notably higher percentage compared with White and Black respondents. Black respondents showed the lowest intention to increase contributions, though still at a substantial 73%. The difference between Hispanic and Black respondents was particularly noteworthy, with a gap of 12 percentage points that was statistically significant (p = 0.0275).

Overall, 79% of all respondents indicated that they would contribute more with the Saver’s Match, while 21% said they would contribute the same amount. The high percentage of respondents reporting that they would contribute more suggests a strong positive effect across all groups, with Hispanic respondents showing an above-average response to the Saver’s Match in terms of contribution intentions. This finding could have important implications for tailoring retirement savings policies and outreach efforts to maximize their effectiveness across diverse populations.

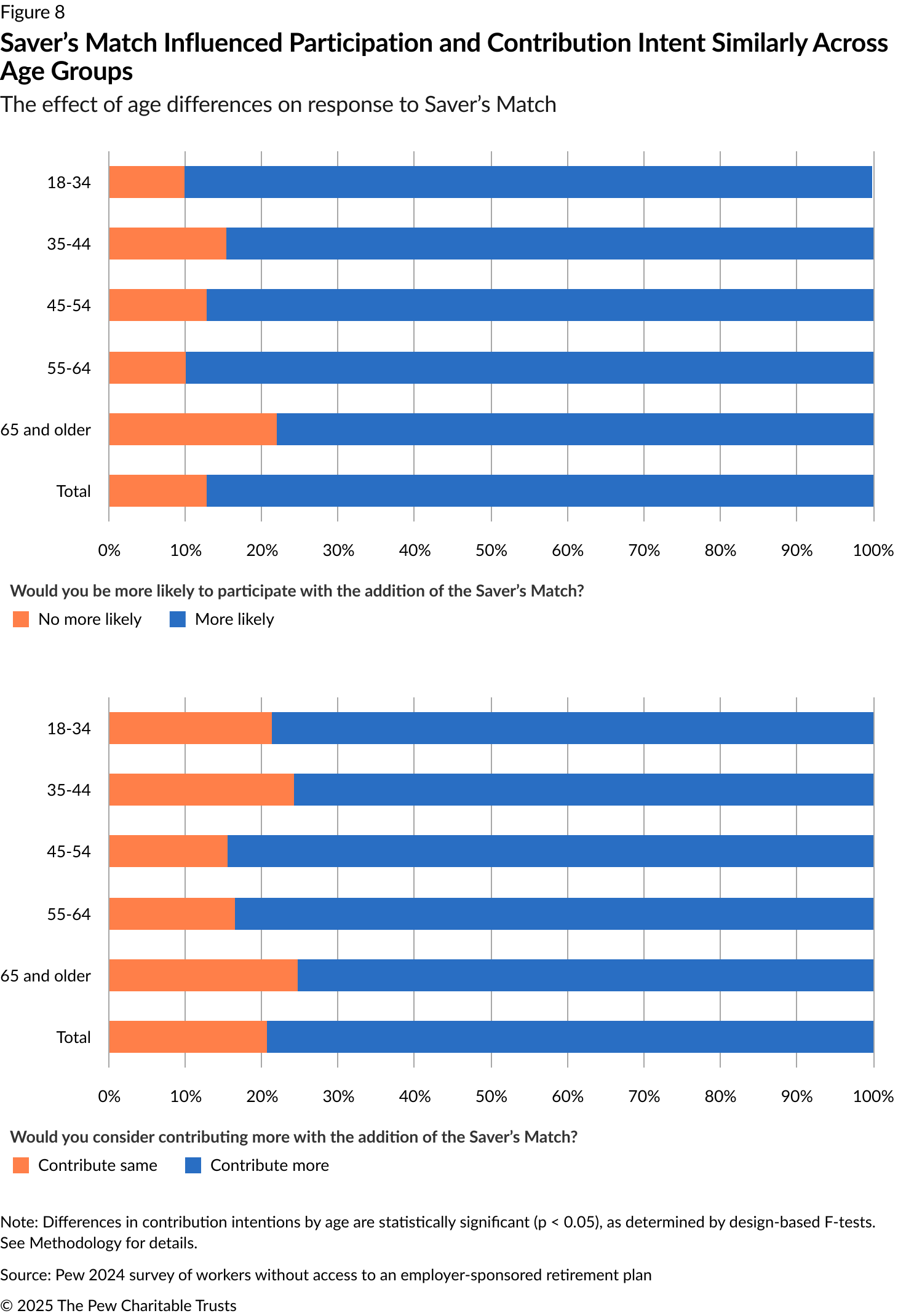

Where there were differences in how much more likely respondents within each age group would be to participate in the presence of the Saver’s Match, these differences across all ages were not statistically significant (p = 0.0781). There was a similar range of those interested in contributing more with the addition of the Saver’s Match—75% of the 65 and older age group and 84% of the 45-54 and 55-64 age groups said they would contribute more. Again, these differences across all ages were not statistically significant (p = 0.3089).

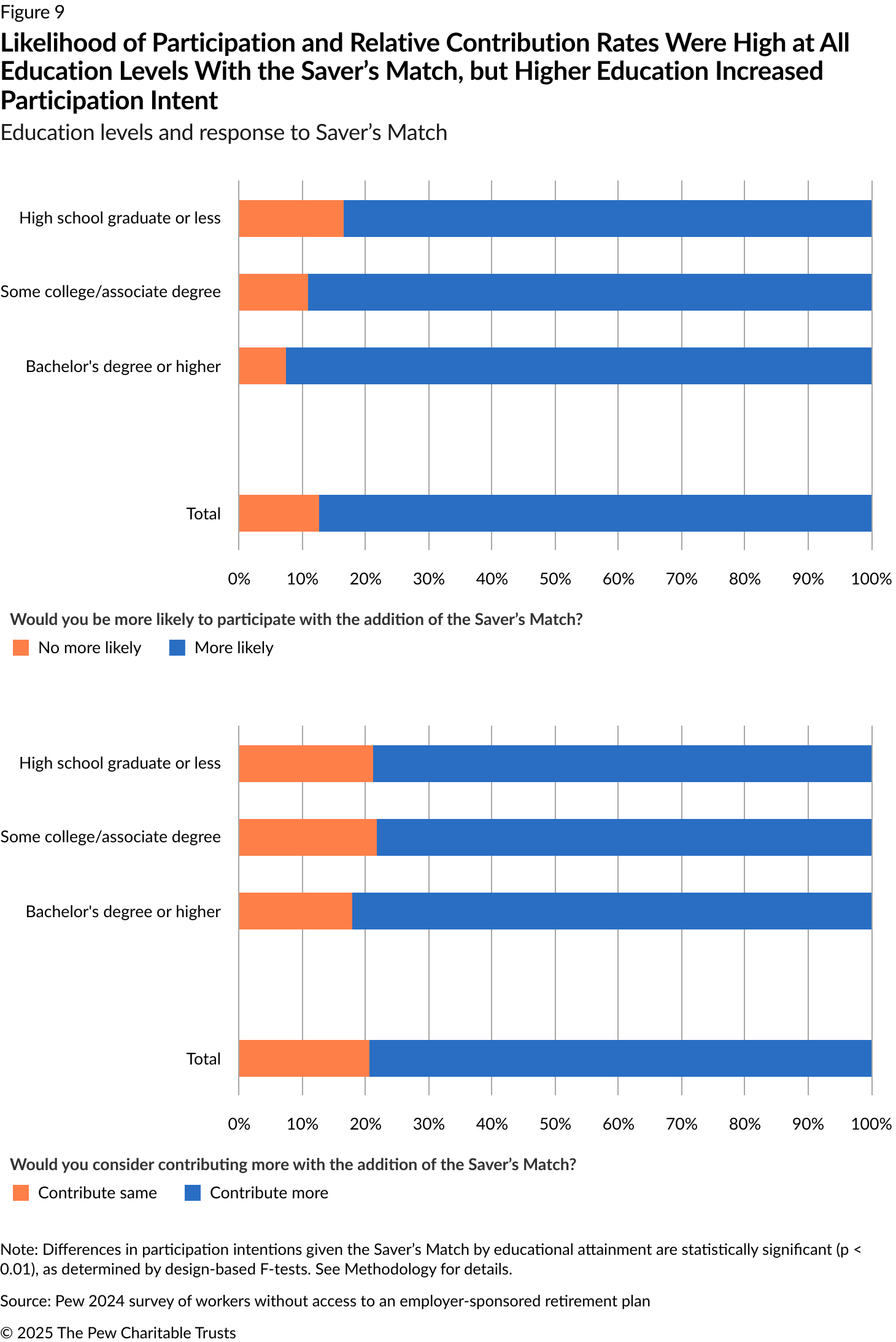

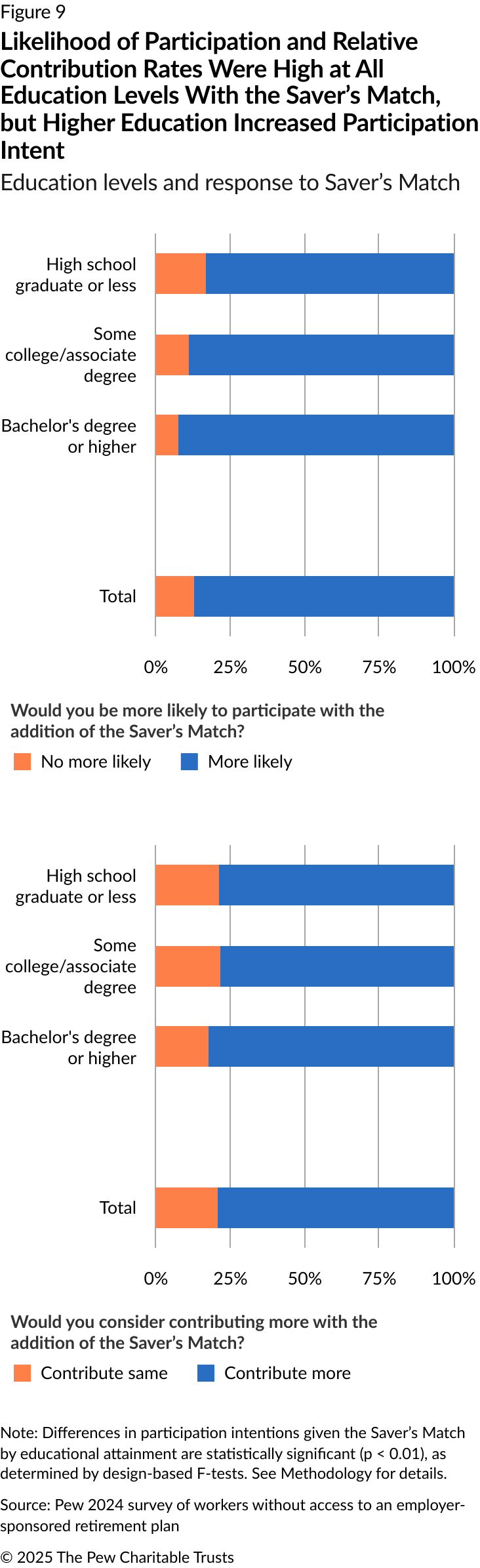

There was a statistically significant relationship between educational attainment and increased likelihood of participation in response to the Saver’s Match (p = 0.0056). Higher education levels corresponded to increased likelihood of participation; respondents with at least a bachelor’s degree showed the highest increase in participation likelihood (93%) with the Saver’s Match. Respondents of all education levels were statistically equally likely to say that the Saver’s Match would lead them to contribute more (p = 0.6220).

The introduction of a hypothetical Saver’s Match caused a large majority of respondents at all education levels to be more interested in participating in an auto-IRA program. But the survey did find a statistically significant relationship between level of education and the desire to participate in an auto-IRA with the Saver’s Match: Respondents with higher levels of education were more likely to respond more favorably compared with individuals with less education. This difference suggests that Saver’s Match proponents should consider tailoring outreach and educational materials to effectively communicate the benefits of the Saver’s Match to individuals with lower educational attainment.

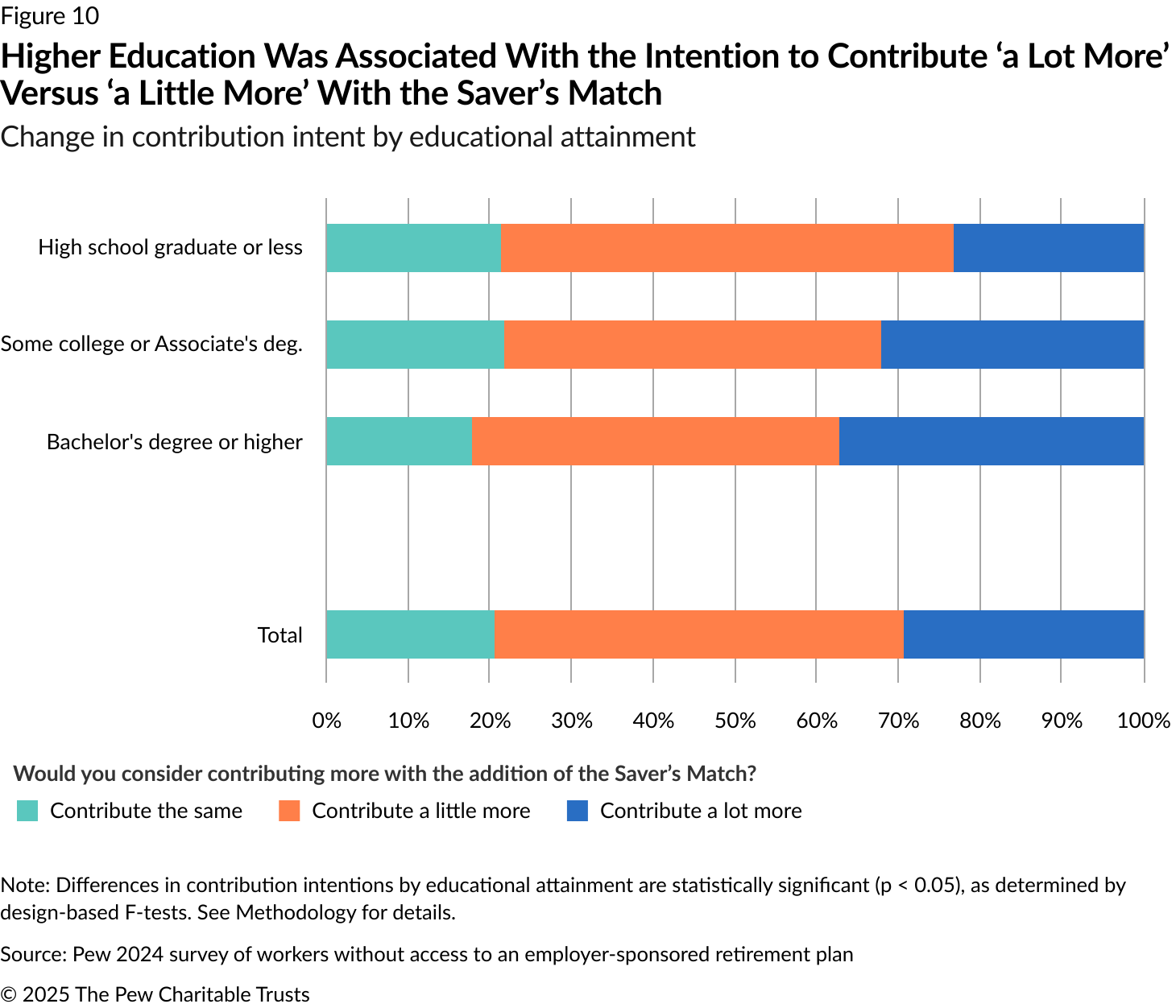

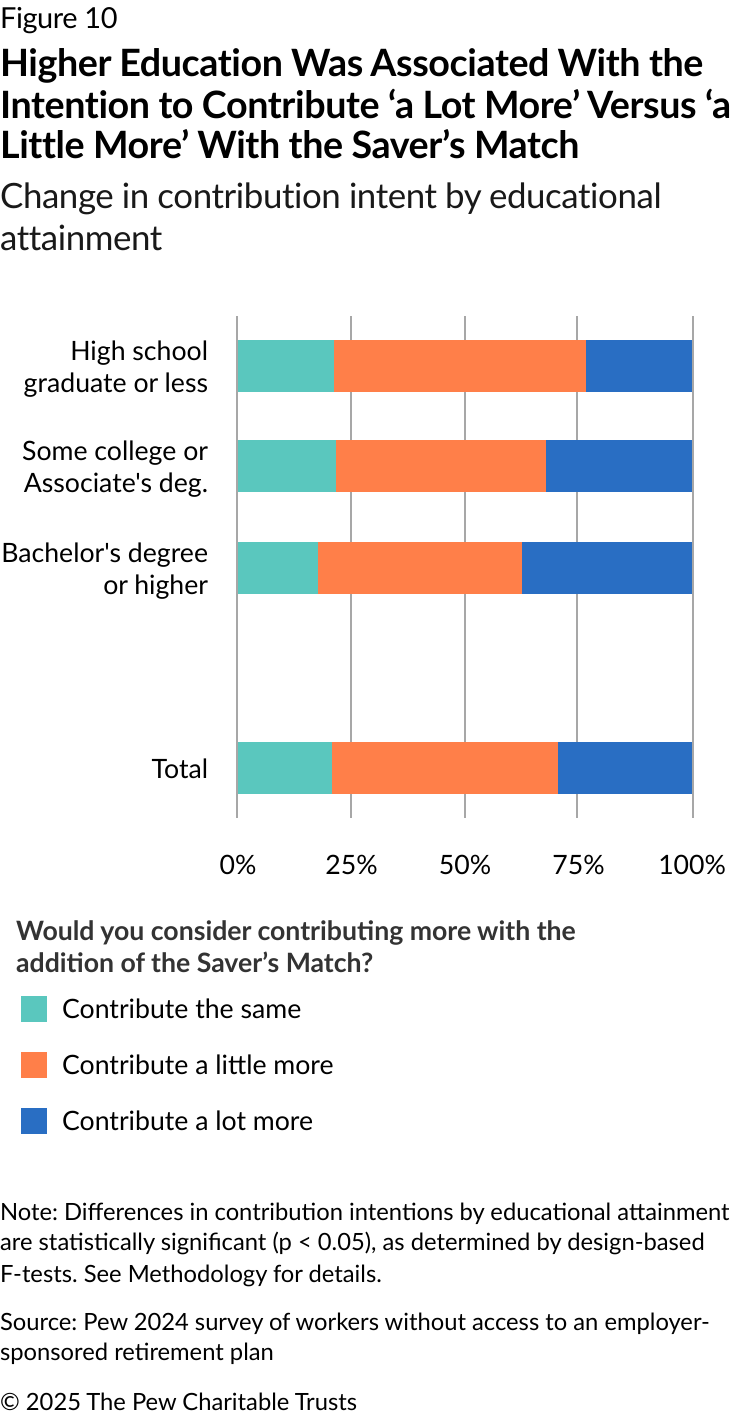

There was a statistically significant relationship between educational attainment and intended contribution levels (p = 0.0381). Respondents who had no more than a high school diploma were the least likely to say they would contribute a lot more (23%) compared with those with some college (32%) and those with at least a bachelor’s degree (37%). However, the group with a high school education or less was the most likely to say they would contribute a little more (56%), compared with those with some college (46%) or at least a bachelor’s degree (45%). This result suggests that while those with lower educational attainment were willing to increase their contributions, they were more likely to consider relatively smaller increases.

Overall, the Saver’s Match appears to be effective as an incentive across all education levels, Its impact on participation increases with education level, while its effect on contribution levels is more complex, potentially reflecting differing financial circumstances and priorities across educational attainment groups.

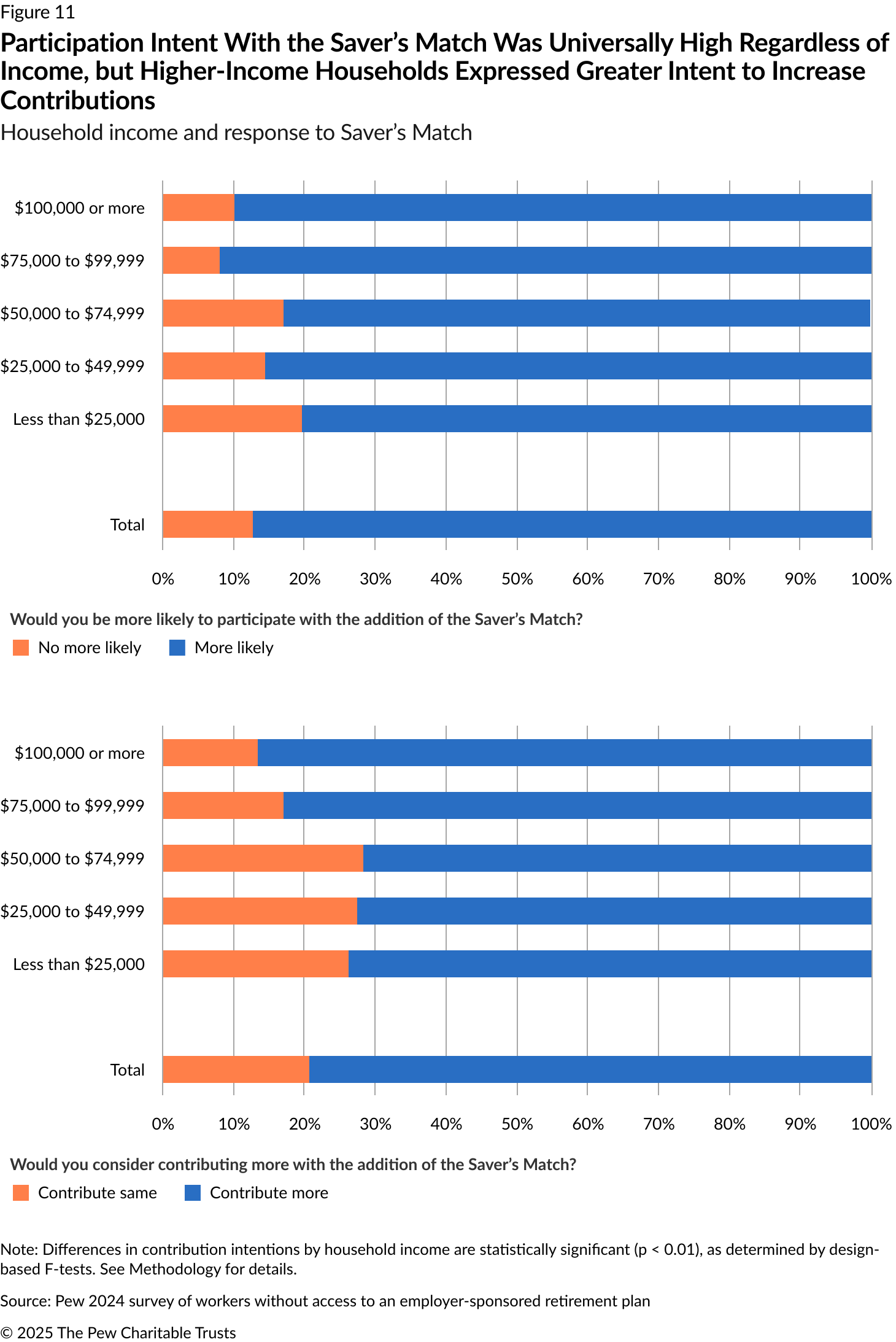

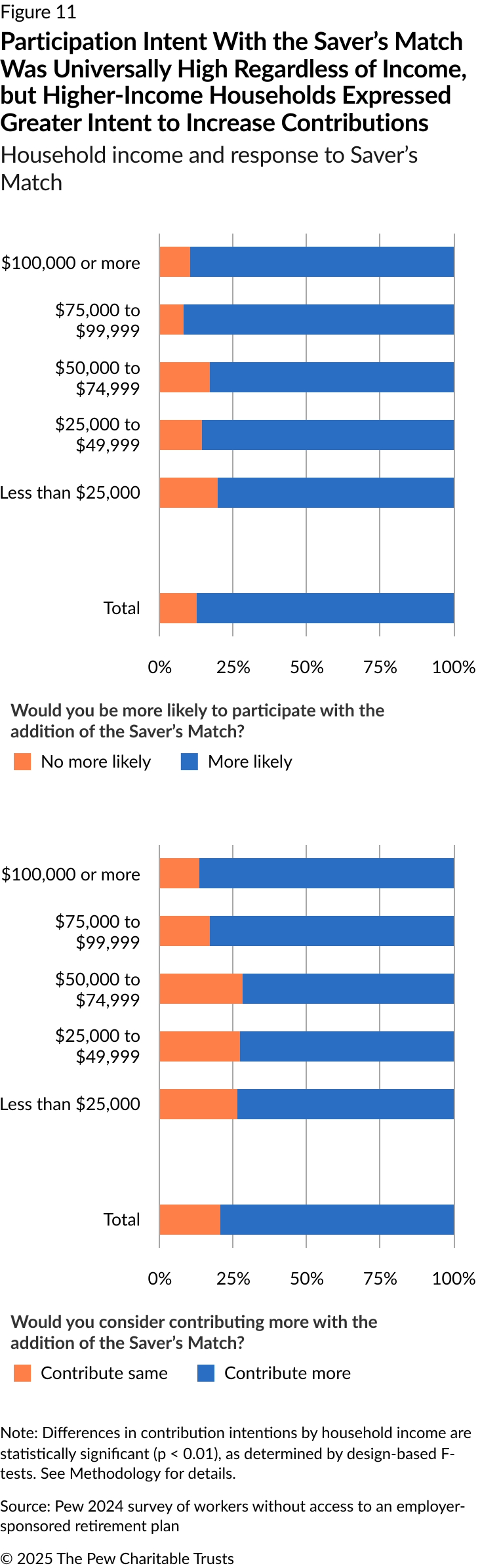

The effect of the Saver’s Match on participation and contribution intentions by household income reveals distinct patterns. While the relationship between income and increased participation likelihood was not statistically significant (p = 0.0733), the data showed some variation by income level. Lower-income groups, particularly those earning less than $25,000, showed the smallest increase in participation likelihood (80%), but this increase was still substantial. Between 80% and 86% of those earning less than $50,000—the primary target population for the Saver’s Match—reported being more likely to participate in an auto-IRA with the addition of the match. This finding highlights the broad appeal of the Saver’s Match among eligible groups.

The impact of the Saver’s Match on contribution intentions across income levels was statistically significant (p = 0.0028) and showed a clear pattern: Higher-income respondents were more likely to say they would consider increasing their contributions. However, large majorities—73% to 74%—of respondents earning less than $50,000 said they would increase their contributions. This finding is critical because the Saver’s Match is specifically designed to incentivize saving among these lower-income groups.

The Saver’s Match is means tested and phases out at higher incomes: for married filing jointly, $41,001-$71,000; for heads of households, $30,751-$53,250; for single filers, $20,501-$35,500. Although higher-income respondents ($75,000 or more) expressed greater interest in participating and contributing with the Saver’s Match, by design they are ineligible. But the data suggests that the audience for which the Saver’s Match was designed will respond well.

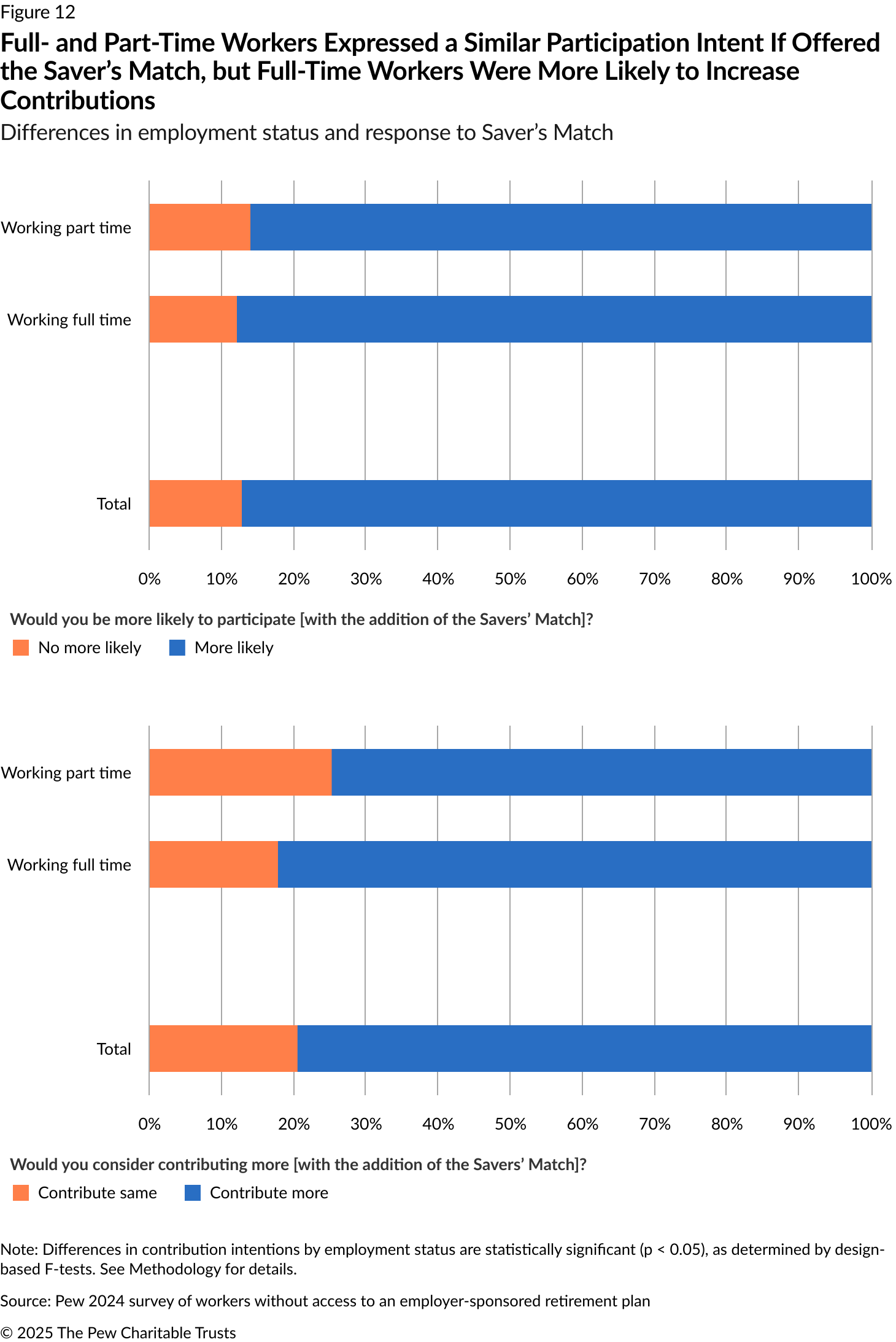

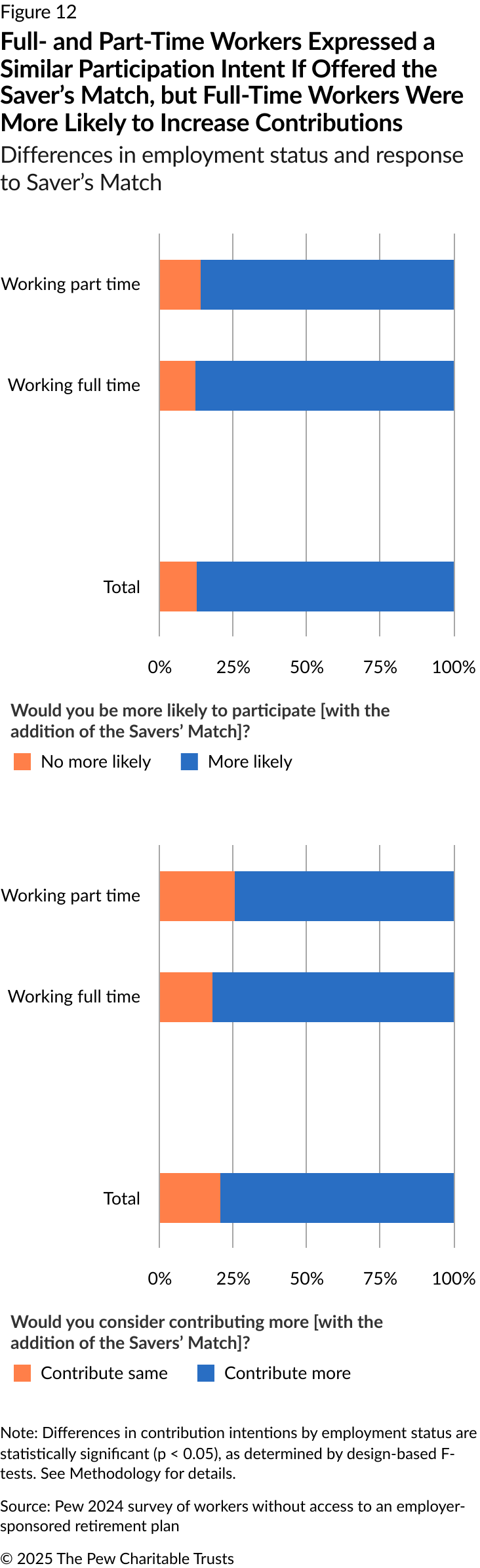

The Saver’s Match had a similarly strong positive effect on survey respondents’ intention to participate in an auto-IRA regardless of full- or part-time employment status. For participation likelihood, there was no statistically significant difference between full-time and part-time workers (p = 0.4862). Full-time workers showed a slightly higher increase in participation likelihood (88%) compared with part-time workers (86%).

However, there was a statistically significant difference between full-time and part-time workers’ intention to increase contribution levels, with full-time workers more likely to do so (p = 0.0324). This difference of approximately 7 percentage points indicates that while the Saver’s Match positively influences both groups, its impact on increasing contribution levels was stronger among full-time workers.

Despite this difference, a substantial majority of both full-time and part-time workers indicated an intention to increase contributions, underscoring the broad appeal and effectiveness of the Saver’s Match across employment types.

Gender, marital status, and number of children

The Saver’s Match broadly increased program interest and contribution intentions, with no statistically significant differences in participation or contribution intent by gender, marital status, or number of children in the household. The Saver’s Match prompted similar increases in participation and contribution intentions across those subgroups, with respondents generally reporting comparable levels of participation interest and contribution intentions.

Overall, while this survey found some variations in the magnitude of the effect of the Saver’s Match across different racial and ethnic, educational, income, and employment status groups, these differences were generally not dramatic. This finding suggests that the Saver’s Match could be an effective tool for increasing retirement savings across diverse demographic groups.

Conclusion

The vast majority of Americans save for retirement through their workplaces, but nearly half of the country’s private sector workforce—about 57 million workers—don’t have access to a workplace retirement plan.6 This lack of access has created a widening gap between what many workers have set aside for retirement and what they will need. The findings of this report provide insights into the potential effectiveness of the Saver’s Match as a policy tool in conjunction with state-sponsored auto-IRA programs, with important implications for retirement savings policy and program design.

The results of Pew’s survey consistently demonstrate that the Saver’s Match is likely to have a strong positive effect on both the desire of workers to participate in auto-IRA programs and the amount of money they save. These effects were visible across diverse demographic groups. The high overall rates of increased participation likelihood (87%) and the intention to increase contributions (79%) suggest that the Saver’s Match could be a powerful lever in addressing the retirement savings gap in the United States.

The Saver’s Match appears to be particularly effective in reinforcing the intentions of those who are already inclined to participate in auto-IRAs: 94% of this group said they were even more likely to participate with the introduction of the federal matching contribution. This finding suggests that the Saver’s Match could significantly boost enrollment rates in state auto-IRA programs. The substantial positive effect on those who were initially unlikely to participate in an auto-IRA (with 52% becoming “more likely”) indicates that the Saver’s Match could also be an effective tool for expanding the reach of state auto-IRA programs to previously disengaged individuals.

The uniformly positive effect across racial and ethnic groups suggests that the Saver’s Match could help address retirement savings disparities by encouraging broader participation among groups that have traditionally lacked access to workplace-based retirement benefits.

The Saver’s Match was designed to help low- and moderate-income households—defined as households with an annual income of $35,500 or less for single filers and $71,000 or less for married couples filing jointly—save for retirement. This survey found that a large majority of respondents in those income categories—80% to 86%—said they would be more likely to participate in an auto-IRA when they were informed about the federal Saver’s Match. Income limits ensure that only those in the low-to-moderate income ranges will benefit, making the match well-targeted.

The Saver’s Match shows great promise as a policy tool to boost retirement savings across diverse populations. By addressing the nuances discussed in this report and continuing to refine implementation, policymakers can significantly enhance the financial security of many low- and moderate-income Americans in their retirement years. The strong positive survey responses across demographic groups suggest that the Saver’s Match could be a key component in creating more effective retirement savings policies that reach all types of households and all racial and ethnic groups.

However, realizing these potential benefits will require addressing several technical and operational barriers. For example, most participants in state auto-IRAs are saving in Roth retirement accounts, which are recognized for determining eligibility for the federal match. But Saver's Match deposits cannot go into a Roth IRA—they must be deposited in a traditional IRA. This distinction creates a fundamental structural barrier: Roth accounts offer operational simplicity for state programs, but they inadvertently prevent participants from receiving the Saver’s Match benefit in that same account.

Additionally, many eligible auto-IRA participants face practical obstacles to claiming the federal match. Many may not have a federal tax liability and may not file federal tax returns, making them unable to claim the match even if they have saved money in an auto-IRA and are eligible. And if the claiming process is complicated—if, for example, it requires an entirely new tax form—that may further prevent eligible participants from receiving the match.

To ensure that the Saver’s Match fulfills its potential to strengthen retirement security, particularly for low- and moderate-income workers participating in state auto-IRA programs, policymakers should focus on five key implementation priorities as outlined in Pew’s response to the joint Department of the Treasury and the Internal Revenue Service request for comment regarding implementation of Saver’s Match contributions (Notice 2024-65).7

- Automation is critical. Wherever possible, the IRS should use existing data to calculate match eligibility and amounts, automatically populate forms to streamline verification, and direct Saver’s Match funds into the appropriate accounts with minimal manual input from savers.

- The claiming process must be simple and intuitive. Clear instructions, visual cues, and integrated tools—especially within free and widely used tax preparation software—can reduce confusion and increase participation.

- Options should be created for those who don’t file federal tax returns. These include simplified ways to claim the match, similar to those in the IRS’ existing nonfiler sign-up tool; partnerships with community groups and tax assistance programs; and outreach tailored to those who are most likely to benefit from the Saver’s Match.

- Robust administrative systems will be essential. The IRS should develop systems and procedures—similar to those used for handling tax refund issues or unclaimed credits such as the earned income tax credit—to address account errors, contribution mismatches, and incomplete claims. These processes should be designed to protect a person’s eligibility to receive the Saver’s Match even if a claim isn’t completed in the initial filing year.

- Communication must be broad, accessible, and well-timed. A coordinated effort across government agencies, tax preparers, employers, payroll processors, and state programs would help raise awareness and increase participation when the match becomes available in 2027.

These recommendations would help ensure that the strong interest in the Saver’s Match demonstrated by this Pew survey translates into actual increased retirement savings for workers who need it most. The implementation of these recommendations would require careful consideration of administrative feasibility, cost implications, and regulatory requirements—and in some cases may require changes to statute—but they represent important steps toward achieving the full potential of this promising policy tool.

Methodology

From April to May 2024, The Pew Charitable Trusts fielded a survey on attitudes about wealth among 1,132 workers who do not have access to a workplace retirement plan such as a 401(k). The survey oversampled Black and Hispanic respondents, allowing for meaningful comparisons across racial and ethnic groups. Responses were appropriately weighted to ensure that the sample was representative. Two respondents were excluded from the analysis after quality checks revealed potentially unreliable data, as indicated by implausibly rapid survey completion times and evidence of “straight-lining,” in which respondents selected the same option across multiple survey items, suggesting biased and inaccurate responses.

The first set of questions measured respondents’ interest in a generic state-sponsored automated retirement savings plan (auto-IRA). A subset of questions was designed to assess the impact of the federal Saver’s Match on participation and contribution intentions.

For key survey items measuring participation and contribution intentions, respondents chose from three response categories (“Not likely,” “Somewhat likely,” and “Very likely”). In analyzing these responses, researchers sometimes combined responses (e.g., “Somewhat likely” and “Very likely”) to create binary measures (“Likely” and “Not likely”). This decision was based on several factors, including:

- Linguistic interpretation, as terms such as “Somewhat likely,” “Somewhat more likely,” “I would contribute a little more” or “I would contribute a lot more” indicate movement toward participation or action rather than maintenance of the status quo (e.g., “I would contribute the same amount”). The validity of this approach was confirmed through comparison with ordered logistic regressions using the full three-category measures, where this binary coding better preserved the directionality of the original measure than alternatives.

- Theoretical coherence with patterns in financial decision-making (e.g., those with household incomes of $100,000-plus being more willing to make or increase contributions).

- An alternative approach, in which the middle category was combined with the status quo (no participation/no action). This yielded similar estimates that did not substantially alter the key findings presented in this report. Differences primarily consisted of marginal results moving toward statistical significance or significant results moving toward marginal significance.

To test for statistically significant differences across respondent subgroups (e.g., by age, race/ethnicity, household size), Pew researchers relied on design-based F-tests. These tests account for the survey’s design—which included probability weighting—to provide estimates of variance and assess whether observed differences in responses are likely due to chance or reflect actual differences between subgroups. Differences with a probability value (p-value) below 0.05 are considered statistically significant.

Limitations of the analysis

There are limitations to this report’s approach that are important to keep in mind when considering the results. These include:

- Self-reported intentions: This analysis relies on self-reported intentions rather than actual behavior. While intentions are a strong predictor of behavior, there may be discrepancies between what respondents say they will do and what they actually do.

- Hypothetical scenario: Respondents were reacting to a hypothetical program that might not fully capture their behavior in a real-world setting.

- Short-term perspective: The survey captures immediate reactions to the Saver’s Match but does not address long-term savings behavior or the persistence of the effect of the Saver’s Match.

- Sample size limitations: Some demographic subgroups had small sample sizes, limiting the robustness of conclusions for these groups.

Despite these limitations, this report provides strong evidence for the potential of the federal Saver’s Match to significantly enhance the effectiveness of state-sponsored auto-IRA programs, offering policymakers valuable insights for designing and implementing retirement savings initiatives that can help address the pressing issue of retirement insecurity in the United States.

Acknowledgments

Pew consulted with various experts and stakeholders in the development of research materials for the survey described in this report, and the team would like to thank external advisers Luisa Blanco-Raynal, Cindy Hounsell, Annika Little, and Hector Ortiz.

This report itself benefited from feedback and guidance offered by external reviewers Catherine Collinson, CEO and president, Transamerica Institute; and Leah Mayor, senior director, Asset Funders Network. Although they provided constructive suggestions on the content, neither they nor their organizations necessarily endorse Pew’s findings or conclusions.

The main researcher and author for this brief was Pew officer Andrew Blevins, who wishes to thank a host of colleagues for providing communications, creative, editorial, and research support for this work. They include Travis Plunkett, John Scott, Kim Olson, Mark Hines, Theron Guzoto, John Murphree, Zach Bernstein, Omar Martinez, Gabriela Domenzain, Briana Okebalama, Bernard Ohanian, Carol Hutchinson, Dave Lam, Reagan Ortiz, Drew Swinburne, and Andy Qualls.

Endnotes

- John Sabelhaus, “The Current State of U.S. Workplace Retirement Plan Coverage” (working paper, Pension Research Council, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, 2022), https://repository.upenn.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/53f6523d-7c37-4052-add0-676774a6181a/content.

- “State Automated Retirement Programs Would Reduce Taxpayer Burden From Insufficient Savings,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, May 11, 2023, https://www.pew.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2023/05/11/state-automated-retirement-programs-would-reduce-taxpayer-burden-from-insufficient-savings.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “Who’s In, Who’s Out,” 2016, https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2016/01/retirement_savings_report_jan16.pdf.

- “Comment from The Pew Charitable Trusts Re: Request for Comments Regarding Implementation of Saver’s Match Contributions (Notice 2024-65),” Regulations.gov, Nov. 5, 2024. https://www.regulations.gov/comment/IRS-2024-0034-0081.

- The survey question ignored participant income and represented the maximum possible Saver’s Match even though some respondents earned too much to qualify for full benefits. Actual benefits phase out based on income at the following bands: single filers: $20,501-$35,500; head of household: $30,751-$53,250; married filing jointly: $41,001-$71,000.

- John Sabelhaus, “The Current State of U.S. Workplace Retirement Plan Coverage.”

- “Comment from The Pew Charitable Trusts,” Regulations.gov.