New Housing Slows Rent Growth Most for Older, More Affordable Units

Data shows that limited supply is associated with greatest rent increases in low-income neighborhoods

The nationwide housing shortage has driven rents up more in low-income neighborhoods than in the U.S. overall, but in areas that have recently added large amounts of housing, rents have fallen the most in lower-income neighborhoods with older buildings, according to an analysis of publicly available housing data.

A large body of research has already established that when there is a shortage of homes, the cost of housing rises rapidly, and when housing is plentiful, affordability improves. But most new housing is expensive, prompting questions about the impact of additional housing supply on older apartments.

A new analysis by The Pew Charitable Trusts begins to provide some answers. These results are relevant for policymakers concerned about renters’ displacement as the costs of housing rise. The findings suggest that not allowing more homes to be built—even for high-income residents—pushes up all rents, making it harder for low-income tenants to remain in their neighborhoods.

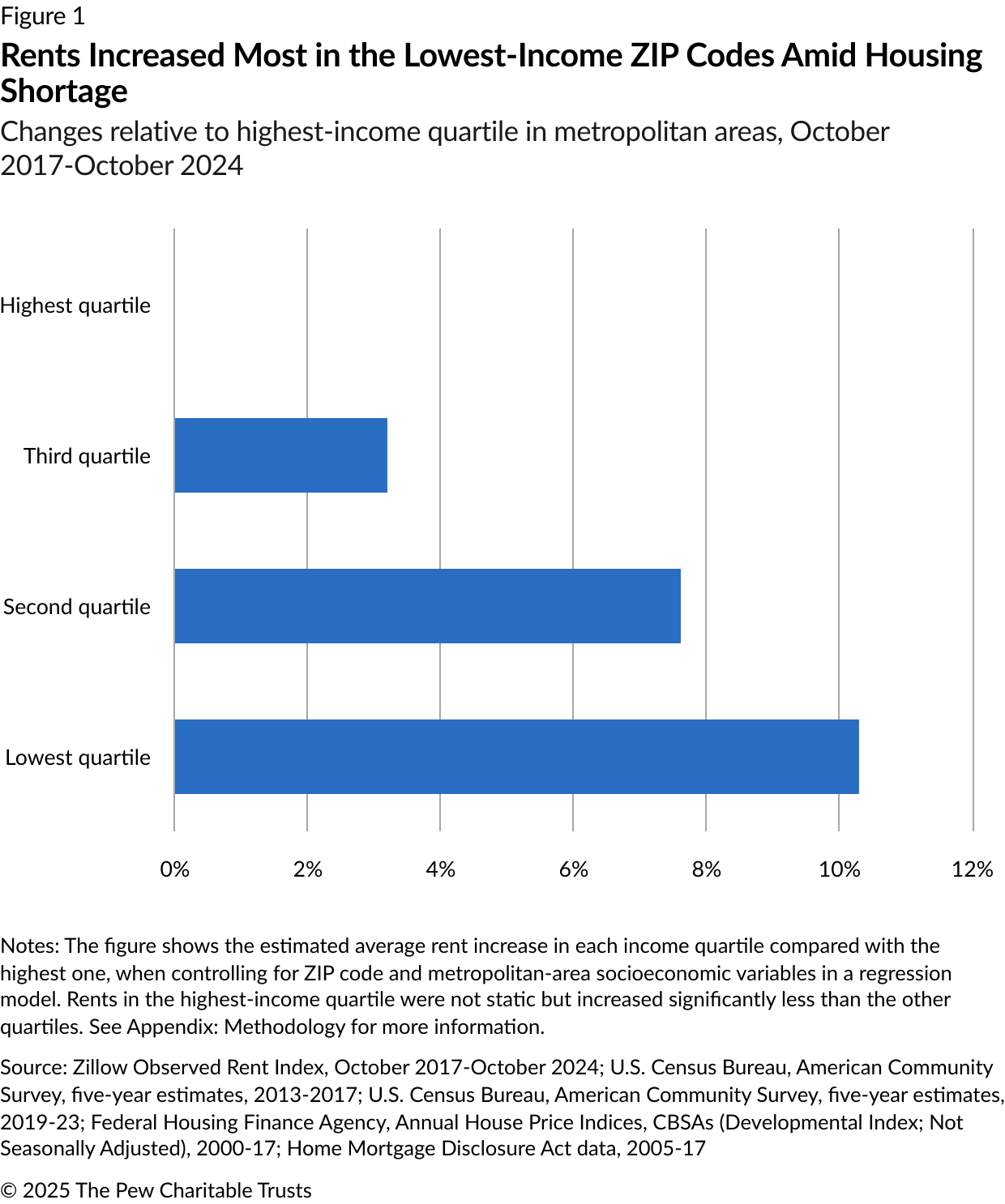

The U.S. faces a shortage of 4 million to 7 million homes, a reality driven especially by restrictive zoning codes. Data from Zillow, a comprehensive source of local rental and housing information, indicates that rents increased by 49% in U.S. metro areas from October 2017 to October 2024. To see how rents changed in areas with different income levels, Pew researchers looked at the change in each individual ZIP code tracked by Zillow and located that ZIP code’s median income in publicly available data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. Then, they compared rent change by ZIP code by income quartile, relative to the highest income quartile, controlling for the socioeconomic characteristics of the ZIP code and the metropolitan area in which each is located. The bottom quartile had median incomes below $43,302 in 2017, while the top quartile had median incomes above $69,804 in 2017. The lowest-income quarter of ZIP codes faced an average rent increase that was 10 percentage points more than the highest-income quarter of ZIP codes.

When not enough homes are built in high-income neighborhoods, people who would have lived in those neighborhoods can usually afford to move into middle-income neighborhoods, and middle-income residents can usually afford to move into low-income neighborhoods, but residents of low-income neighborhoods have nowhere to turn. Their options are limited, and the data indicates that they keep their housing by absorbing large rent increases, but many can’t afford to do so—a record 27% of renters now spend more than half of their income on rent. People are generally considered cost-burdened when they spend more than 30% of their income on rent, a category that includes nearly half of U.S. renters.

Building more housing—both throughout a metropolitan area and in a particular neighborhood—keeps rent growth lower overall, but it takes the most pressure off of older, less-expensive housing, essentially mitigating the competitive process just described. Pew’s analysis of the 1,654 ZIP codes tracked by Zillow throughout U.S. metropolitan areas suggests that every 10% increase in a market’s housing supply (using American Community Survey data) from 2017 to 2023 correlated with rents growing 5% less from 2017 to 2024, controlling for a variety of factors. About one-fifth of ZIP codes covered by Zillow were in metropolitan areas with unit growth of at least 10% from 2017 to 2023.

New supply at the neighborhood-level matters, too. A 10% increase in a ZIP code’s housing supply means average rents grew by 1.4% less than they did in a ZIP code with no supply growth. (About one quarter of ZIP codes covered by Zillow had unit growth of at least 10% from 2017 to 2023). In dollar terms, the average Zillow ZIP code rent increased from $1,525 in October 2017 to $2,225 in October 2024. That’s a rise of about $700 or 46%.

In high-supply metropolitan areas that added at least 10% to their unit stock, this change amounts to at least $470 less in payments over the course of a year, and at least $120 less in high-supply ZIP codes. Importantly, housing markets are regional: Increasing the whole region’s housing supply has four times the impact on local rents compared with just adding local supply.

And limits on new housing have a clear impact. Previous analysis from Pew shows that cities such as Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York that have severely limited their housing growth in recent decades have seen costs rise and displacement occur.

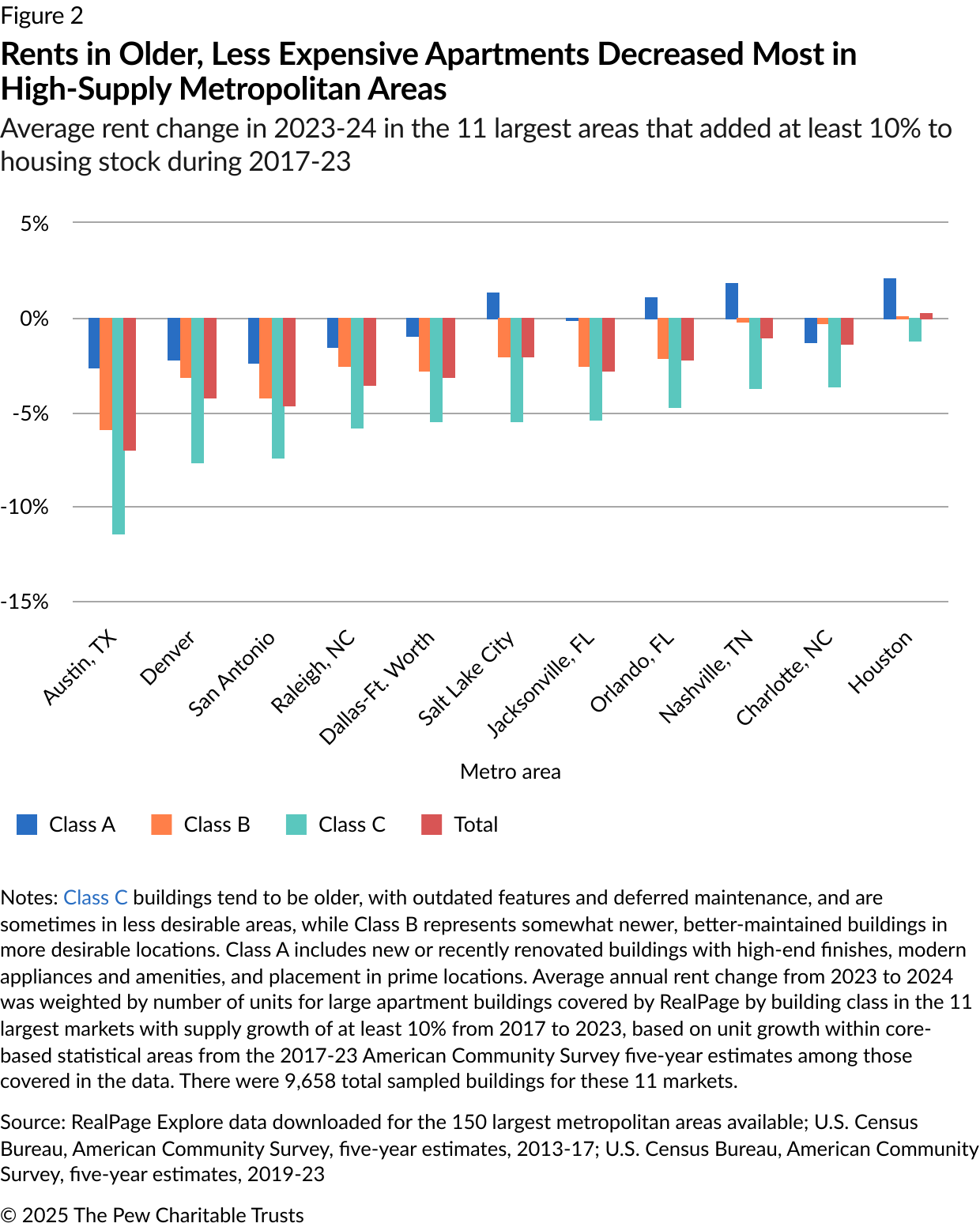

On the other hand, cities such as Houston, Minneapolis, and New Rochelle, New York, that have added housing at a rapid clip have curbed both rent growth and displacement. Eleven large metropolitan areas increased their housing supply by at least 10% from 2017 to 2023. Collectively, they saw average rents decline from 2023 to 2024 for large apartment buildings tracked by RealPage Explore, a property management software company that provides rent and building characteristics data for properties with at least 50 units in metropolitan areas nationwide.

In each metropolitan area, the steepest rent declines were for Class C apartments—those in older and less expensive buildings, as first observed by RealPage and Jay Parsons, an economist based in Dallas. (See Figure 2.) So even though most of the new apartments and condominiums built were not subsidized and may have had rents higher than low-income residents could afford, the new supply helped push rents down in older, less-expensive units by reducing the competition among those seeking homes that were no longer as scarce.

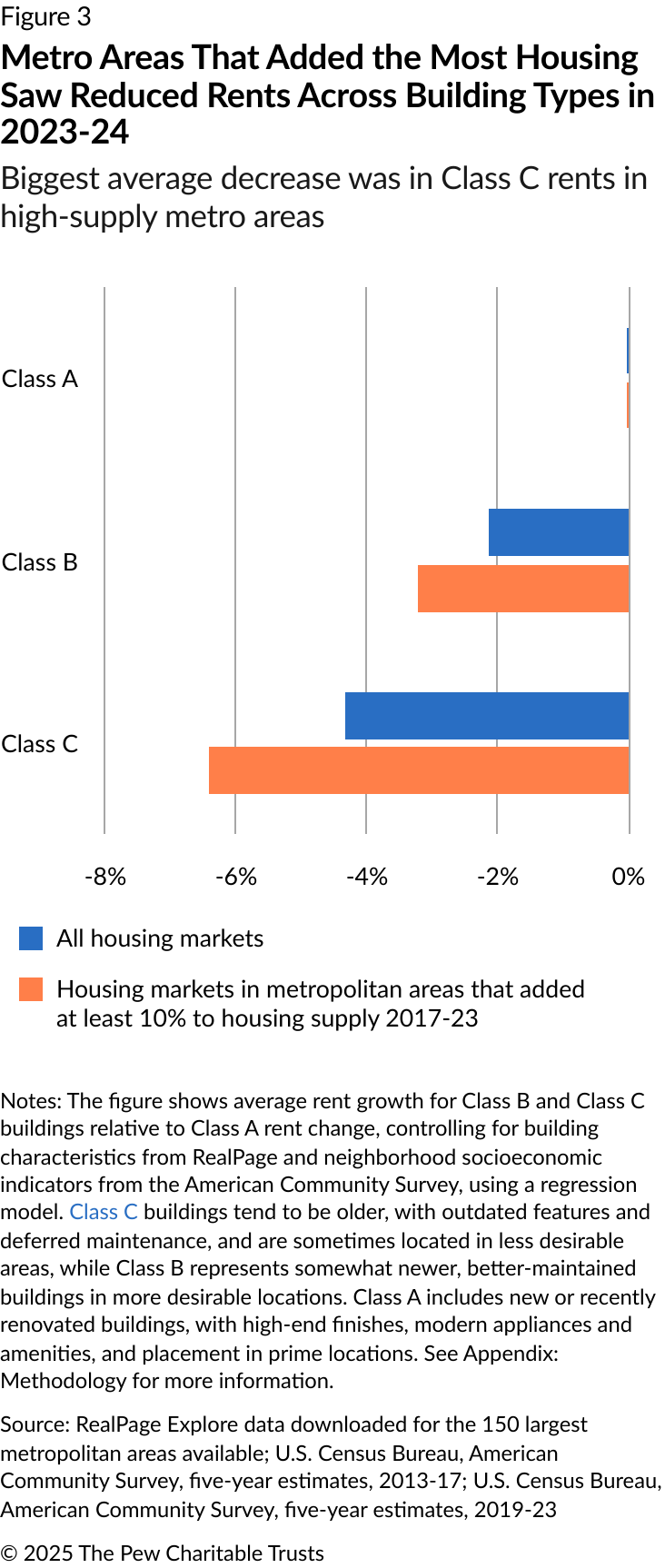

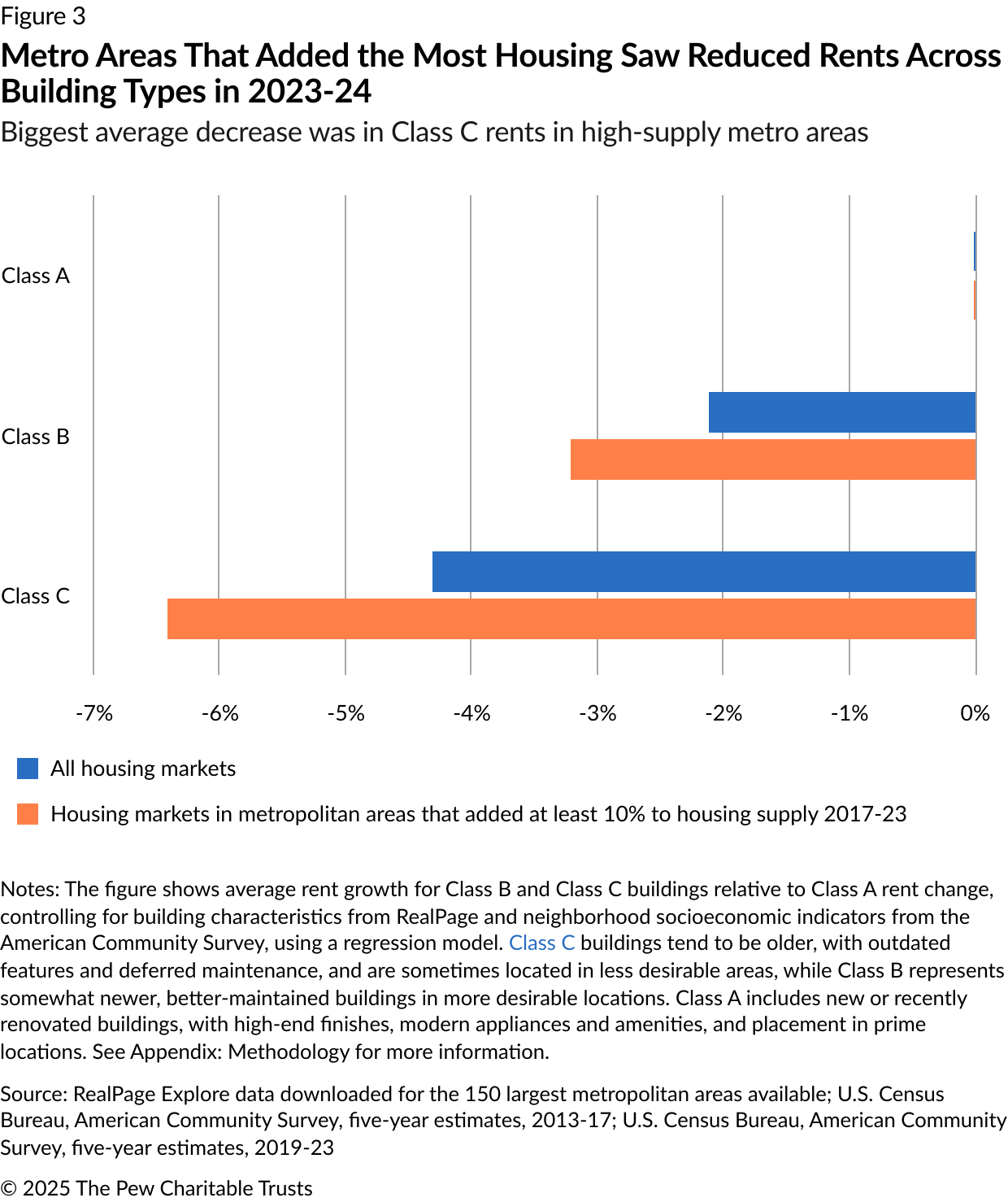

And the same pattern played out more broadly. Looking at more than 41,000 large apartment buildings in 223 metro areas, there was a clear trend: Class C rents decreased more, relative to those for units in Class A buildings. In high-supply metro areas (those that increased their housing stock by at least 10% from 2017 to 2023), rent growth was slower than in average markets. Crucially, rent growth slowed most for Class C units, demonstrating that the additional supply was especially helpful to people living in lower-cost apartments. (See Figure 3.)

Even though new housing is usually expensive, the reason for the decline in Class C rents is straightforward. Economist Evan Mast, an assistant professor at the University of Notre Dame, has documented that when new apartments are built in high-income neighborhoods, they set off moving chains. The new residents of those homes tend to move in from high-income neighborhoods, but the people who move into the homes they vacate come from slightly less affluent neighborhoods, and so on. The chains quickly reach communities with below-average incomes, freeing up as many as 70 homes there for each 100 market-rate (unsubsidized) homes built in high-income neighborhoods, according to Mast’s research.

Housing shortages don’t just drive up costs—they’re regressive. Maintaining restrictive zoning that exacerbates the housing shortage puts vulnerable tenants in a more precarious position by burdening them with steep rent increases. Allowing enough homes for everyone improves affordability overall, but the evidence shows it benefits low-income renters most.

Seva Rodnyansky is a manager, Dennis Su is an associate, and Alex Horowitz is a project director with The Pew Charitable Trusts’ housing policy initiative.