Deep-Sea Mining Could Complicate Fishing and Other Marine Activities

The United Nations Ocean Conference, which drew 15,000 people (including 64 heads of government) to France in June, spotlighted the broad recognition – spanning geographies, industries and cultures – that the ocean needs to be conserved.

Among the notable outcomes of the convening, four additional countries announced their support for a moratorium or precautionary pause on deep-sea mining for minerals in areas of the ocean beyond any country’s jurisdiction. Currently, 37 governments support this call.

Also during the conference, more than a dozen nations ratified the High Seas Treaty, also known as the Agreement on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction, or BBNJ Agreement. The treaty will enable the creation of high seas marine protected areas and, as of 19th September 2025, has received its 60 required ratifications, triggering a process for it to enter into force in January 2026. The United Kingdom signed the agreement in September 2023 but, as of early October 2025, had not yet ratified it.

Despite this global support for protecting international waters, there is a growing push from a handful of governments and businesses to begin mining of the deep seabed. However, many experts question the economic viability of mining and processing minerals such as cobalt, nickel, manganese and lithium from the deep ocean when they are commonly found elsewhere and are already facing a decrease in anticipated demand as manufacturing technologies evolve.

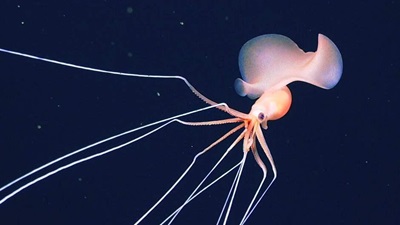

But economics is not the only reason to reconsider seabed mining. Scientists know that the deep ocean is home to significant biodiversity and that mining would cause irrevocable damage to the fragile marine environment. Mining activities have the potential to negatively impact vital ecosystem services that people rely on, such as the healthy functioning of fisheries. The world’s regional fisheries management organizations have already established rules governing the fishing of particular species in areas of the high seas. But scientists have found that as the temperature of the ocean increases, commercially fished species, including tuna, will probably be pushed into areas where extensive mining is now planned. Mining consequences, such as plumes of sediment that travel throughout the water column, could disrupt the feeding and reproduction patterns of tuna, increase their stress hormone levels and expose them to toxic metals that could harm humans who consume tuna.

Amid these concerns, the Global Tuna Alliance and other seafood industry groups have joined governments and other sectors in calling for a moratorium on deep-sea mining. Nevertheless, as governments are negotiating a regulatory framework through the International Seabed Authority (ISA) to govern deep-sea mining in areas beyond any country’s jurisdiction, some governments are pushing to allow mining to commence despite a lack of science to determine whether it can be done without harming the marine environment.

It is important that nations not view seabed mining activities in isolation. Legal experts have determined that the countries working to develop the ISA’s deep-sea mining regulations must consider and, where appropriate, incorporate other international laws and climate protection. Seabed mining would overlap with other marine management and conservation commitments – including those set by international bodies responsible for managing fisheries; the BBNJ Agreement’s aim to establish ocean protections; and a commitment by nearly 200 countries to protect 30% of the ocean by 2030, a goal known as “30 by 30.” For example, the nations that are part of the Convention on Biological Diversity declared an area of the Atlantic to be ecologically significant because scientists believe it’s possible that life on Earth began there. Yet many of these nations also are members of the ISA, which allows that region to be explored for future mining.

Cooperation with other ocean users is also critical. As governments continue to negotiate deep-sea mining regulations at the ISA, collaboration is vital for ensuring that international laws are developed and implemented consistently. A moratorium on deep-sea mining would provide the necessary time and space for nations to effectively coordinate, uphold their legal obligations and honor commitments to safeguard the ocean, its biodiversity and its resources for current and future generations.

Julian Jackson leads the seabed mining work for The Pew Charitable Trusts’ ocean governance project.

This piece was first published in The Geographer’s autumn 2025 issue, a magazine from the Royal Scottish Geographical Society.