How Massachusetts Addresses Substance Use Disorders in Primary Care Settings

As policymakers expand office-based treatment, other states can learn from this promising approach

Overview

Massachusetts’ approach to integrating opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment into primary care settings has been a model for the nation since 2007.1 Under the state’s nurse care manager (NCM) model, providers receive financial support to improve access by hiring dedicated nursing staff to assess and monitor patients and coordinate their care. This approach allows doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants to serve more patients. In 2023, as a result of this and other treatment efforts, 79% of Massachusetts Medicaid enrollees with OUD received medication—the standard of care for the condition—far exceeding the national median of 60%.2

The NCM model is one way to provide office-based addiction treatment (OBAT) outside the specialty substance use disorder (SUD) treatment system, helping to expand access to services. And policymakers have recognized the benefits of applying this treatment more widely. From June 2021 to July 2022, the highest rates of substance related deaths in Massachusetts were due to opioids and alcohol.3 Meanwhile, more than half of all opioid-related overdose deaths involved cocaine, a stimulant.4 So in 2022, the Massachusetts Bureau of Substance Addiction Services expanded the model to reach people with alcohol and stimulant use disorders.5

With this promising approach, which builds on existing systems of care, Massachusetts can serve as a model for other states looking to establish or expand their own OBAT models to serve people with a range of SUDs.

The nurse care manager model

The NCM model relies on nurses with training in chronic disease management and patient education.6 In this approach to OBAT care, nurse care managers screen patients for substance use disorder; a physician or other authorized prescriber confirms the diagnosis and prescribes buprenorphine if indicated.7 Nurse care managers then lead medication initiation and management, develop treatment plans, educate patients, coordinate complex care among providers, and document treatment adherence. This model allows prescribers to see more patients and expand access to care.8

But the NCM model cannot successfully expand treatment access unless clinicians are incentivized to provide such care. So it’s critical that policymakers implement a payment approach that adequately reimburses providers for expanding services. Massachusetts has done this by funding the NCM model through a mix of Medicaid reimbursement, state general funds, and federal dollars—including the Substance Use Prevention, Treatment, and Recovery Services Block Grant and the State Opioid Response Grant—to pay for services that are not covered by Medicaid.9 Providers may also opt in to receive additional funds to pay for wraparound services, such as transportation to appointments and community outreach activities like partnering with soup kitchens and visiting homeless encampments to build relationships with people who may need care.10 According to Nicole Schmitt, director of the Office of Strategy and Innovation at the bureau, this outreach helped providers to engage more people in treatment.11

How nurse care managers have helped patients with OUD

Studies have found that the NCM model helped to expand access to OUD treatment in Massachusetts. Three years after the model was developed at Boston Medical Center and expanded to 14 federally qualified health centers (facilities that are federally funded to provide primary care services to individuals regardless of ability to pay), the number of health care providers prescribing buprenorphine at these locations increased from 24 to 114. Further, the number of patients remaining in treatment for over a year more than doubled, from 32% in 2010 to 67% in 2013.12 In a sign of the model’s financial stability, seven of the 14 sites even expanded their program size beyond the initial grant requirements.13

Elsewhere, a study in five states also showed that nurse care managers help to increase the volume of OUD treatment provided, with patients participating longer.14 Patients also described the care as nonjudgmental and non-stigmatizing and said they were motivated to stay in treatment.15

How primary care can support people with substance use disorders

Many people with SUD can be treated in a primary care setting, especially if providers are equipped to address health and social needs that are sometimes complex. Services can include:

SUD screening and connections to specialty treatment: Providers can screen patients to identify SUDs and connect them to specialty care such as withdrawal management or residential treatment if needed.16 Primary care can also provide continuing treatment after discharge from a specialty facility.

Medication initiation and management: Providers can prescribe Food and Drug Administration approved medications for OUD and alcohol use disorder (AUD) and off-label medications for stimulant use disorder; these include buprenorphine and naltrexone for OUD and naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram for AUD.17 Meanwhile, providers can refer patients seeking methadone to specialty facilities called opioid treatment programs.18 And while there are no FDA-approved medications to treat stimulant use disorder, off-label medications—including prescription stimulants for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; nonstimulant medications for depression, seasonal affective disorder, and smoking cessation; and naltrexone—can help to reduce stimulant use.19 Contingency management—a behavioral approach that uses incentives to help people reduce stimulant use—is another effective treatment.20

Addressing substance-related health problems: Patients with SUDs often have comorbid medical conditions associated with their substance use. For example, people who use stimulants or drink heavily have a greater risk of cardiovascular conditions than the general population.21 And injection drug use increases the risk of viral infections such as HIV and Hepatitis C.22 Primary care providers can help people who use drugs reach their treatment goals by identifying and treating these comorbid conditions.23

Care coordination: Primary care organizations can centralize health information across the multiple providers who may be serving a patient and develop individualized care plans.24 They could also connect patients to services related to housing, transportation, and food insecurity. Providing these care coordination services increases treatment engagement and reduces substance use severity.25

These providers can still support patients who need specialty SUD care by addressing physical health needs and providing ongoing care when a patient no longer needs intensive treatment services.

Expanding substance use treatment in office-based settings in Massachusetts

In August 2022, the Massachusetts Bureau of Substance Addiction Services expanded the NCM model to include care for people with alcohol and stimulant use disorders. As of 2025, more than 40 sites across the commonwealth offered OBAT services through a contract with the bureau—a sizable increase over the 14 federally qualified health centers delivering this care in 2007.26

To add these services, OBAT sites receive technical assistance and training from bureau-contracted providers. For instance, Massachusetts is using grant funding to train providers on outpatient alcohol withdrawal management so that providers are comfortable offering the service. “Training can ensure that the person who is given outpatient withdrawal management has the right supports at home or in their community, because outpatient withdrawal management is doable. Not everyone needs an inpatient level of care,” said Jen Miller, director of grants and innovation at the bureau.27

Providers can also participate in a free 12-session training and support videoconferencing program offered by Boston Medical Center.28 Miller said this technical assistance is “run and developed by a program that implements OBAT services, so they’re keenly aware of some of the challenges and successes.”29

Using the nurse care manager model to help patients with substance use disorders beyond OUD

As clinicians and Massachusetts officials adjusted treatment approaches to meet the evolving nature of substance use—and updated their payment approach to align with this evolution—providers were able to treat more people with varied substance use-related health needs. Overall, OBAT enrollment increased from 3,687 in 2020 to 4,319 in 2024, a 17% increase.

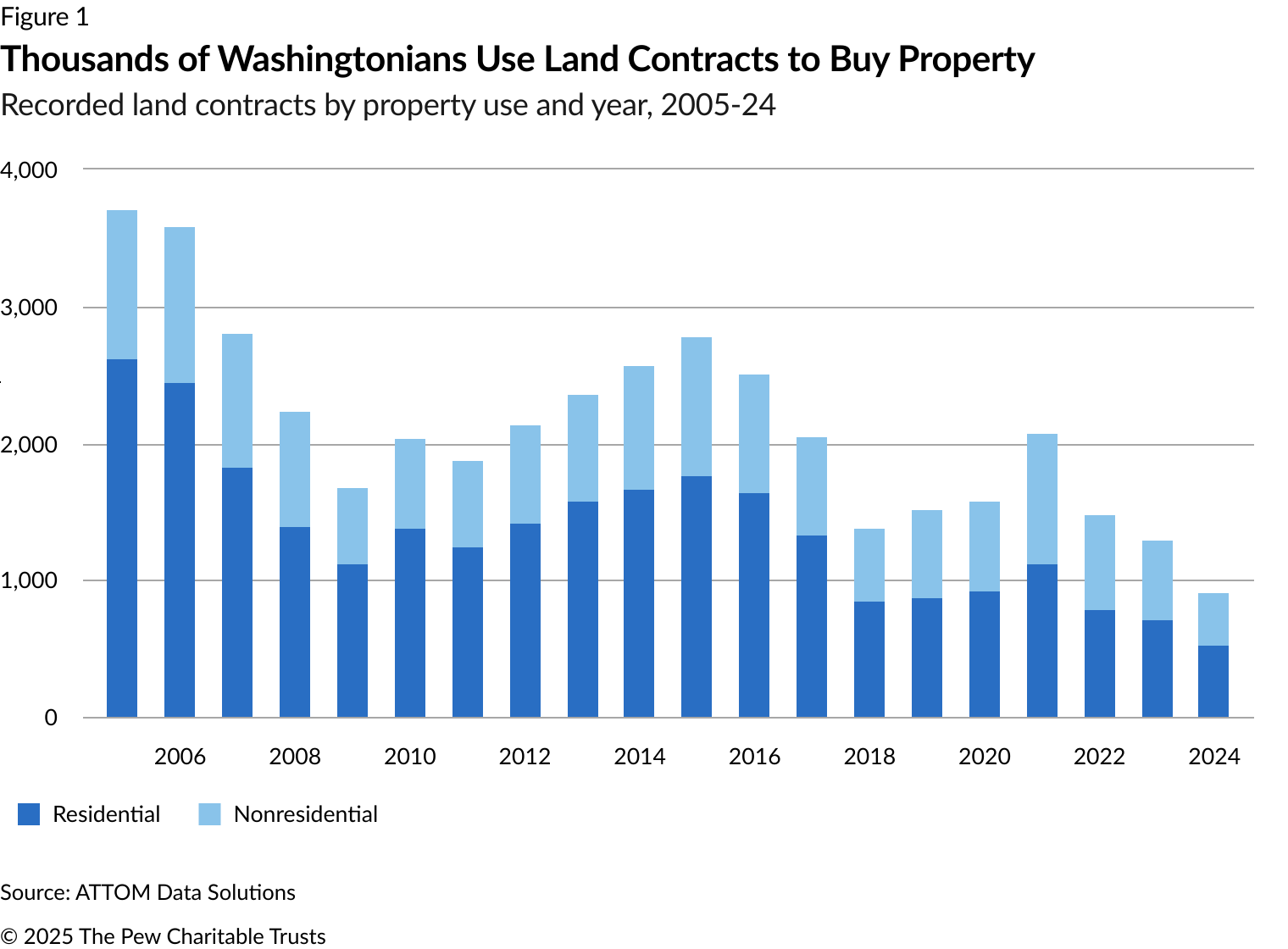

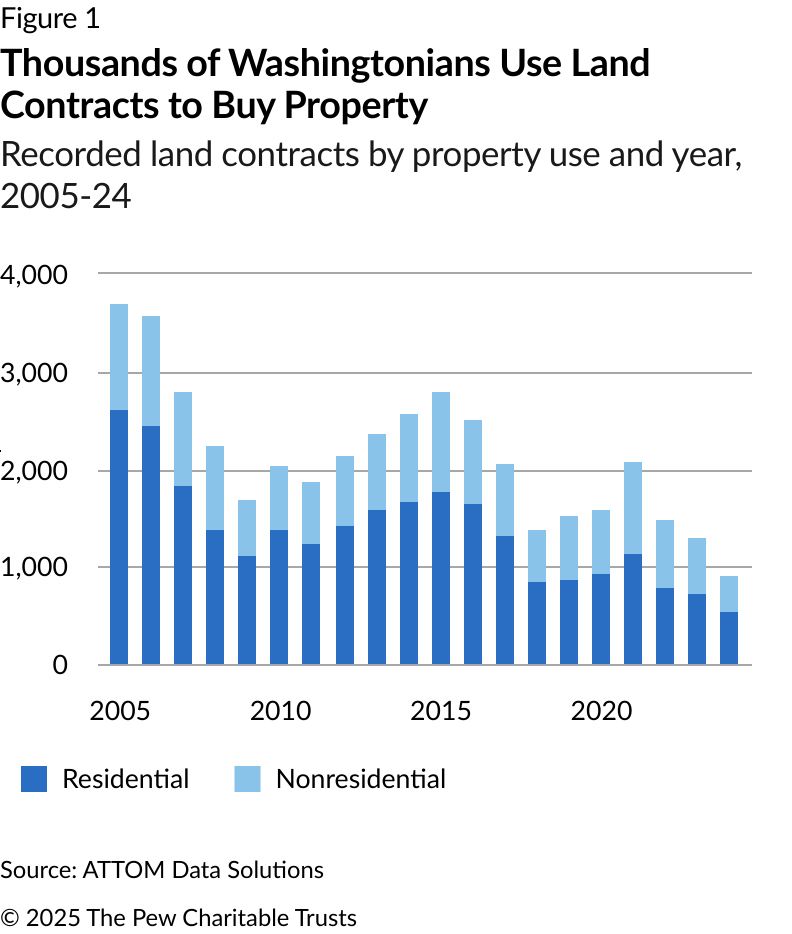

Non-opioid admissions to OBATs in Massachusetts also grew during that period, from 639 (17.4% of admissions) in fiscal year 2020 to 1,682 (39% of admissions) in fiscal 2024, as shown in Figure 1.

Miller noted that facilities began accepting patients who did not have an OUD before the official change because providers recognized a need in their communities. She suggested that the nurse-led aspect of the NCM model encouraged patients to seek care at these facilities because there was less fear or stigma involved. Likewise, Miller noted that OBAT facilities were more accessible compared with other levels of care: “[It] feels less daunting to go to, because your primary care might be just down the hall.”30

Massachusetts’ expansion of the OBAT model came about through recognition that facilities were already providing care for AUD and stimulant use disorder without being paid to do so, according to interviews with Pew.31

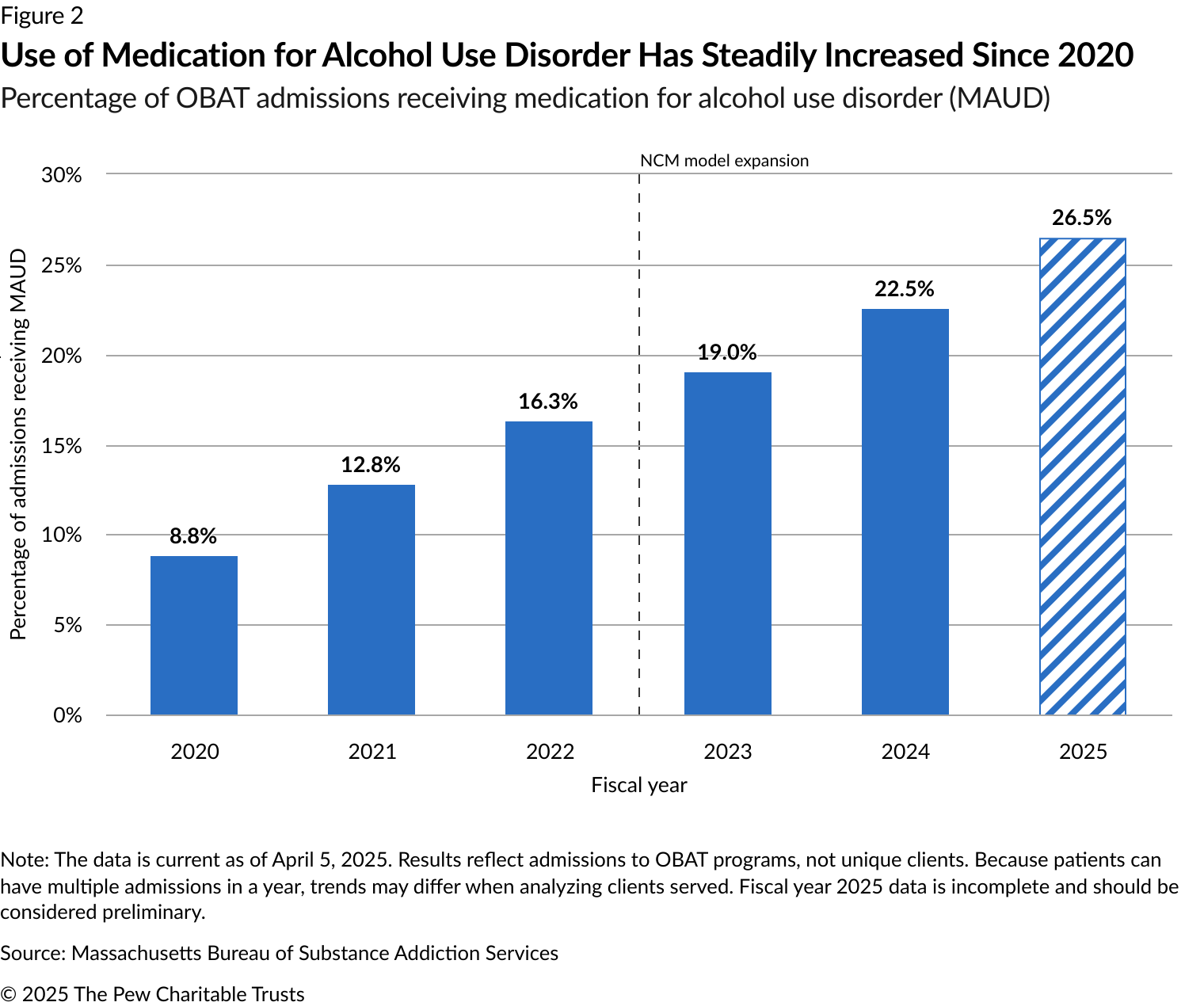

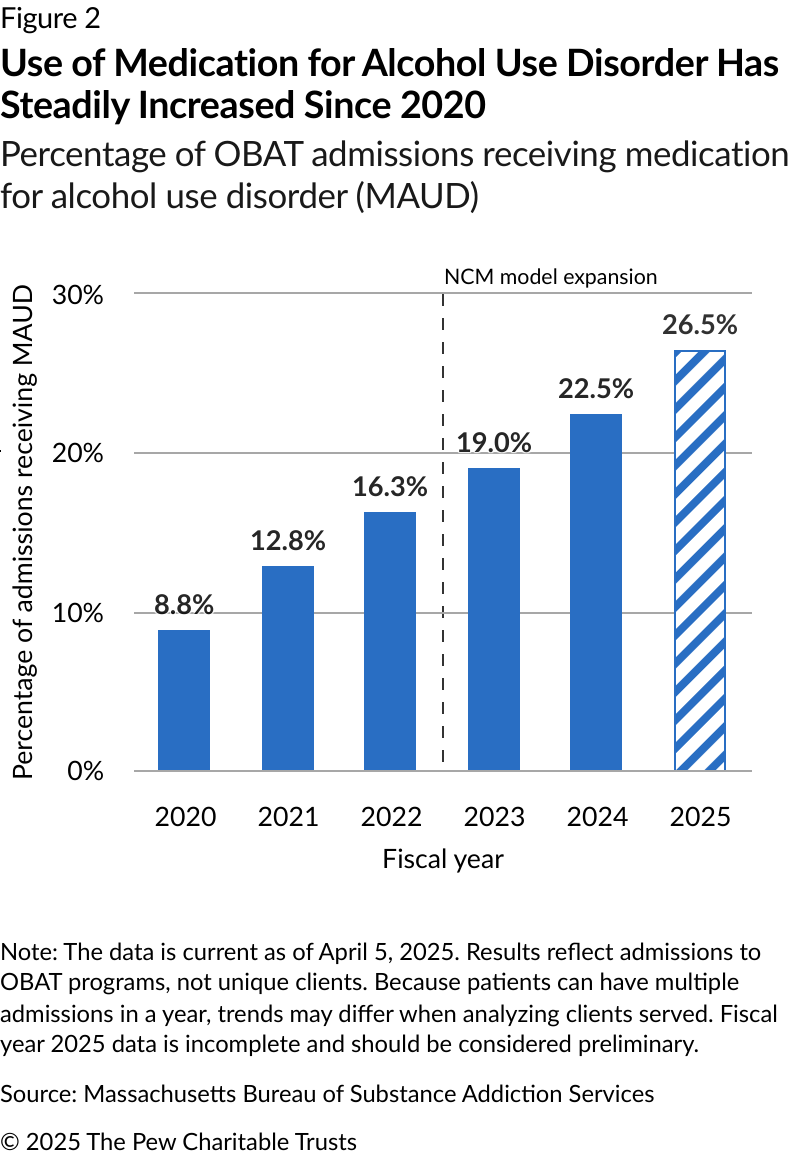

Some patients receiving services before the policy change might have had another substance as their primary concern while still needing OUD treatment. For example, comorbid OUD and AUD are common; a recent meta-analysis found that, among people with OUD, 27.1% also had AUD.32 Further, people with AUD are more than five times as likely to also have OUD compared with people without any SUD.33 The formal transition to OBAT in Massachusetts allows providers to treat individuals with co-occurring SUDs and receive payment for these services. As a result, the number of admissions taking medication for AUD has increased from 295 (8.8% of admissions) in 2020 to 899 (22.5%) in 2024, as shown in Figure 2.

How states can support OBAT models

To save lives and improve health, other states with OBAT treatment models and aligned payment approaches can expand care for people with substance use disorders beyond opioids. In an interview with Pew, Nicole Schmitt, director of the Office of Strategy and Innovation at the Massachusetts Bureau of Substance Addiction Services, advised state leaders to “take a broader perspective and not go down the rabbit hole of focusing on one particular drug.” Schmitt noted that it can be a disservice to be “narrowly focused on opioids and not pay attention to alcohol and stimulants.”34

At least two other states besides Massachusetts have expanded eligibility for OBAT programs. In Virginia, providers receiving enhanced payments for providing buprenorphine and wraparound services can bill at the same rates as those for providing services to people with AUD and stimulant use disorders.35 Similarly, in Michigan, primary care providers can now bill for SUD services, including screening and assessment, care management, counseling, and medication, regardless of the primary substance used by the patient as long as providers can offer the appropriate level of care.36 Michigan also allows people with alcohol and stimulant use disorders to access health home services to better coordinate their care.37 And states without these approaches can establish them with broader eligibility, as Delaware is doing through the Management of Addictions in Routine Care initiative.38

State leaders establishing or expanding OBAT payment models should also consider dedicating funding—such as state opioid response grants (which can be used to address stimulant-use disorder) and the Substance Use Prevention, Treatment and Recovery Services Block Grant, which is not specific to any substance—to offer providers ongoing training and technical assistance with these new services. Previous research on OBAT implementation has demonstrated that offering providers such support increases the likelihood of buprenorphine prescribing, indicating that it might also be helpful in supporting treatment for other SUDs.39 Schmitt described the technical assistance that grantees receive in Massachusetts as “instrumental,” saying that “people may want to do this or see a need to do it, but they may not know how to do it or how to do it well.”40

Massachusetts’ experience demonstrates that state leaders can expand services created for people with opioid use disorder to those with other SUDs—and that pairing these policy changes with provider support can result in improved access to care.

Endnotes

- Colleen T. LaBelle et al., “Office-Based Opioid Treatment With Buprenorphine (OBOT-B): Statewide Implementation of the Massachusetts Collaborative Care Model in Community Health Centers,” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 60 (2016): 6-13, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26233698.

- “Use of Pharmacotherapy for Opioid Use Disorder: Ages 18 to 64 (OUD-AD),” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/quality-of-care/core-set-data-dashboard/measure/Use-of-Pharmacotherapy-for-Opioid-Use-Disorder-Ages-18-to-64-OUD-AD

- “Bureau of Substance Addiction Services (BSAS) Dashboard,” Massachusetts Department of Public Health, https://www.mass.gov/info-details/bureau-of-substance-addiction-services-bsas-dashboard.

- “Bureau of Substance Addiction Services (BSAS) Dashboard,” Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

- “Bid Solicitation: BD-23-1031-ADMIN-ADM07-78592,” Massachusetts Bureau of Substance Addiction Services, Aug. 19, 2022, https://www.commbuys.com/bso/external/bidDetail.sdo?docId=BD-23-1031-ADMIN-ADM07-78592&external=true&parentUrl=bid.

- Boston Medical Center, “Massachusetts Nurse Care Manager Model of Office Based Addiction Treatment: Clinical Guidelines,” 2021, https://www.addictiontraining.org/documents/resources/22_2021_Clinical_Guidelines_1.12.2022_fp_th%2528003%2529.29.pdf. “Care Coordination Strategies for Patients Can Improve Substance Use Disorder Outcomes,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2020, https://www.pew.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2020/04/care-coordination-strategies-for-patients-can-improvesubstance-use-disorder-outcomes.

- Colleen T. LaBelle et al., “Office-Based Opioid Treatment With Buprenorphine (OBOT-B).”

- Boston Medical Center, “Massachusetts Nurse Care Manager Model.”

- Dominic Hodgkin, Constance Horgan, and Gavin Bart, “Financial Sustainability of Payment Models for Office-Based Opioid Treatment in Outpatient Clinics,” Addiction Science & Clinical Practice 16 (2021): 45, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-021-00253-7. Nicole Schmitt (Director of the Office of Strategy and Innovation, Massachusetts Bureau of Substance Addiction Services), conversation with Frances McGaffey, Camille Clark, and Rob Siebers, May 2, 2025.

- Nicole Schmitt, interview.

- Nicole Schmitt, interview.

- Colleen T. LaBelle et al., “Office-Based Opioid Treatment With Buprenorphine (OBOT-B).”

- Colleen T. LaBelle et al., “Office-Based Opioid Treatment With Buprenorphine (OBOT-B).”

- Paige D. Wartko et al., “Nurse Care Management for Opioid Use Disorder Treatment: The PROUD Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial,” JAMA Internal Medicine 183, no. 12 (2023): 1343-54, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37902748/.

- Nisha Beharie et al., ““I Didn’t Feel Like a Number”: The Impact of Nurse Care Managers on the Provision of Buprenorphine Treatment in Primary Care Settings,” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 132 (2022): 108633, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0740547221003597.

- “Primary Care and SBIRT?,” Joanne Byron, American Institute of Healthcare Compliance, May 5, 2021, https://aihc-assn.org/primarycare-and-sbirt/.

- “America’s Most Common Drug Problem? Unhealthy Alcohol Use,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, Dec. 13, 2024, https://www.pew.org/en/research-and-analysis/fact-sheets/2024/12/americas-most-common-drug-problem-unhealthy-alcohol-use.

- Randi Sokol, “After the Mate Act: Integrating Buprenorphine Prescribing Into Mainstream Family Medicine Education and Practice,” Family Medicine 56, no. 2 (2024): 74-75, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10932557/. “Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Improve Patient Outcomes,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, Dec. 17, 2020, https://www.pew.org/en/research-and-analysis/fact-sheets/2020/12/medications-for-opioid-use-disorder-improve-patient-outcomes.

- Masoumeh Amin-Esmaeili et al., “Reduced Drug Use as an Alternative Valid Outcome in Individuals with Stimulant Use Disorders: Findings from 13 Multisite Randomized Clinical Trials,” Addiction 119, no. 5 (2024): 833-43, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11009085/. “The ASAM/AAAP Clinical Practice Guideline on the Management of Stimulant Use Disorder,” Journal of Addiction Medicine 18, no. 1S (2024): https://journals.lww.com/journaladdictionmedicine/fulltext/2024/05001/the_asam_aaap_clinical_practice_ guideline_on_the.1.aspx.

- “Stimulant Use Is Contributing to Rising Fatal Drug Overdoses,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, Aug. 23, 2024, https://www.pew.org/en/research-and-analysis/fact-sheets/2024/08/stimulant-use-is-contributing-to-rising-fatal-drug-overdoses. “The ASAM/AAAP Clinical Practice Guideline on the Management of Stimulant Use Disorder.”

- “Alcohol Use and Your Health,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Jan. 14, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/about-alcoholuse/index.html. Adnan I. Qureshi et al., “Cocaine Use and the Likelihood of Nonfatal Myocardial Infarction and Stroke: Data From the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey,” Circulation 103, no. 4 (2001): 502-06, https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.103.4.502.

- “Getting Off Right: A Safety Manual for Injection Drug Users,” National Harm Reduction Coalition, https://harmreduction.org/issues/safer-drug-use/injection-safety-manual/potential-health-injections/.

- Stephanie A. Hooker et al., “What Is Success in Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder? Perspectives of Physicians and Patients in Primary Care Settings,” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 141 (2022): 108804, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0740547222000861.

- Families USA, “The Promise of Care Coordination: Transforming Health Care Delivery,” 2013, https://familiesusa.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Care-Coordination.pdf.

- Amity E. Quinn et al., “A Research Agenda to Advance the Coordination of Care for General Medical and Substance Use Disorders,” Psychiatric Services 68, no. 4 (2016): 400-04, https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201600070.

- Colleen T. LaBelle et al., “Office-Based Opioid Treatment With Buprenorphine (OBOT-B).” Jen Miller (Director of Grants and Innovation, Massachusetts Bureau of Substance Addiction Services), conversation with Frances McGaffey, Camille Clark, Rob Siebers, April 25, 2025.

- Jen Miller, interview, April 25, 2025.

- “Massachusetts Office Based Addiction Treatment (OBAT) ECHO,” Boston Medical Center Grayken Center for Addiction Training & Technical Assistance, https://www.addictiontraining.org/project-echo/massachusetts-obat-echo/.

- Jen Miller (Director of Grants and Innovation, Massachusetts Bureau of Substance Addiction Services), conversation with Frances McGaffey, Camille Clark, and Rob Siebers, May 2, 2025.

- Jen Miller, interview, May 2, 2025.

- Nicole Schmitt, interview. Jen Miller, interview, May 2, 2025.

- Thomas Santo Jr. et al., “Prevalence of Comorbid Substance Use Disorders Among People With Opioid Use Disorder: A Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis,” International Journal of Drug Policy 128 (2024): 104434, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0955395924001191.

- Moriah R. Harton, Zachary W. Adams, and Maria A. Parker, “Associations of Alcohol Use Disorder, Cannabis Use Disorder, and Nicotine Dependence with Concurrent Opioid Use Disorder in U.S. Adults,” Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology 31, no. 6 (2023): 9981004, https://doi.org/10.1037/pha0000649.

- Nicole Schmitt, interview.

- Dominic Hodgkin, Constance Horgan, and Gavin Bart, “Financial Sustainability of Payment Models for Office-Based Opioid Treatment in Outpatient Clinics.”

- Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, “Coverage of Office Based Substance Use Treatment (OBSUT) Services,” news release, Dec. 1, 2023, https://www.michigan.gov/mdhhs/-/media/Project/Websites/mdhhs/Assistance-Programs/MedicaidBPHASA/2023-Bulletins/Final-Bulletin-MMP-23-61-OBSUT.pdf.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “Michigan Models New Approach to Treating Alcohol and Stimulant Use Disorders,” 2025, https://www.pew. org/fr/research-and-analysis/fact-sheets/2025/05/michigan-models-new-approach-to-treating-alcohol-and-stimulant-use-disorders.

- “Delaware Division of Medicaid and Medical Assistance’s Management of Addictions in Routine Care Model,” Delaware Division of Medicaid and Medical Assistance, 2024, https://dhss.delaware.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/dmma/pdf/dmma_marc_concept_ paper_20240911.pdf.

- Lauren Caton et al., “Opening the ‘Black Box’: Four Common Implementation Strategies for Expanding the Use of Medications for Opioid Use Disorder in Primary Care,” Implementation Research and Practice 2 (2021): https://doi.org/10.1177/26334895211005809. James B. Anderson et al., “Project Echo and Primary Care Buprenorphine Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder: Implementation and Clinical Outcomes,” Substance Use & Addiction Journal 43, no. 1 (2022): 222-30, https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2021.1931633. Linda Zittleman et al., “Increasing Capacity for Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder in Rural Primary Care Practices,” Annals of Family Medicine 20, no. 1 (2022): 18-23, https://www.annfammed.org/content/20/1/18.full.

- Nicole Schmitt, interview.*