Breaking the Plastic Wave 2025

An Assessment of the Global System and Strategies for Transformative Change

Editor’s note: This page was updated on Feb. 6, 2026, to correct the modelled years of healthy life lost from open burning and to fix other minor errors and typos.

Preface

In 2020, The Pew Charitable Trusts and Systemiq published a groundbreaking report, “Breaking the Plastic Wave,” amid significant data gaps on plastic pollution, substantial debate over the scale of the plastic pollution problem and various proposals to meet the challenge. With that report, Pew and our partners sought to move the global discourse forward by identifying a credible roadmap for addressing the problem using existing solutions.

Thanks to countless scientists, academics, organizations and others in the five years since “Breaking the Plastic Wave” was released, the available data and the world’s understanding of how plastic affects people and the planet are vastly improved. In particular, researchers are paying more attention to the serious potential risks that plastic poses for human health and to its significant contributions to global greenhouse gas emissions. And this wealth of information has fueled a significant increase in efforts and policies to reduce plastic pollution around the world. However, global efforts to address these and other risks of plastic and plastic pollution have not been enough, and the scale of the challenge remains significant.

In this update, “Breaking the Plastic Wave 2025,” we draw on this improved information landscape to provide a deeper understanding of the environmental, economic, health and social impacts of plastic. We also explore the global plastic system’s influence on efforts to address some of the world’s greatest challenges. Our aim is to support and encourage decision makers as they respond to critical global issues, evaluate trade-offs and implement solutions. We hope this work will help them seize the opportunities that tackling plastic pollution offers and provide impetus for urgent and ambitious action.

The first “Breaking the Plastic Wave” invigorated and empowered conversations around preventing plastic pollution, and the companion paper published in the journal Science has been cited in subsequent research more than 1,000 times.1 Just as crucial, the report spurred policy and business decisions to tackle this global problem.

Pew also has taken significant steps to ensure that the report’s findings translated into action. Over the past five years, Pew has worked within the European Union to tackle microplastic pollution from tyres and plastic pellets; with negotiators seeking to develop an international, legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, commonly referred to as the U.N. plastics treaty; with the World Trade Organization on efforts to end plastic pollution; and with stakeholders in India, South Africa, the United States and Zambia to analyse plastic waste flows and assess various policy options. We hope that these efforts will not only make a meaningful difference to people and the environment, but also serve as a blueprint for other initiatives to tackle plastic pollution.

In addition, Pew convened Minderoo Foundation, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and World Wildlife Fund to support CDP, a nonprofit that runs the world’s only independent environmental disclosure system, in developing the Scaling Plastics Disclosure initiative, which empowers companies to disclose their plastic-related activities and provides comprehensive and comparable data to decision makers across the global economy. In the initiative’s first year, almost 3,000 companies embraced reporting on plastic through CDP, and in year two, that number nearly doubled to over 5,500.2

Further, Pew is embarking on new work aimed at reducing Americans’ exposure to harmful endocrine-disrupting chemicals, which are known to interfere with human hormone systems. Many of these chemicals are found in plastic products, and a growing body of evidence links their effects with infertility, cancer, diabetes and other health issues. Pew’s initiative focuses on effectively distilling and communicating the science around these chemicals and developing, securing and helping to implement public policies and market actions to better protect human health.3

With the health of people and the planet as our guiding concern, Pew and ICF undertook the research for this new report, in collaboration with the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, Imperial College London, Systemiq and the University of Oxford, drawing on major publications, analyses and reports. A 21-member expert panel and an advisory committee consisting of panel members from the first report and others brought diverse opinions and experiences, with backgrounds including plastic policy, human health, community impacts, microplastics and business.

The results are stark. The global plastic system puts people worldwide at risk, with the most vulnerable bearing the brunt of the impacts. Without action, by 2040, the amount of plastic polluting the environment will more than double; plastic-related greenhouse gas emissions will undermine global efforts to stem planetary warming; and plastic production and waste will threaten the health of growing numbers of people around the world.

However, hope remains. The global community can remake the plastic system and solve the plastic pollution problem in a generation, but decision makers will need to prioritize people and the planet. The path forward will not be easy. Achieving these ambitious goals will require leveraging existing solutions, innovative technologies and collaborations among business, workers and government to deliver transformative shifts in the ways products are manufactured, chemicals are developed and people receive, use and dispose of their products. But the challenges of this effort are far outweighed by its promise – of healthier people, a cleaner environment and a more sustainable global economy.

Tom Dillon

Senior Vice President, Environment and Cross-Cutting Initiatives

The Pew Charitable Trusts

Executive summary

In 2020, amid rising concerns over the scale and impacts of plastic pollution, The Pew Charitable Trusts, Systemiq and their partners published “Breaking the Plastic Wave” (BPW1), which found that the amount of plastic that would enter the ocean each year from municipal solid waste would nearly triple by 2040, increasing from 11 million metric tons (Mt) in 2016 to 29 Mt, unless the global community undertook the ambitious actions identified in the report.

Despite that urgent call, progress towards that study’s vision of coordinated measures across the entire plastic system to reduce pollution has yet to be realized, and in the intervening five years, 570 Mt of plastic pollution has entered the land, air and water worldwide.

To help illuminate the consequences and implications of that slow progress, we conducted a new, more comprehensive analysis of plastic pollution in Earth’s waters, land and air. (All figures in this report are rounded to two significant digits, and any apparent inconsistency is the result of this rounding. For complete data see the technical appendix.)

This resulting report is an update to and expansion of BPW1 that builds on the better data that has become available over the past five years to examine all major sectors of the global plastic system. For more information on data advancements, see Appendix D.

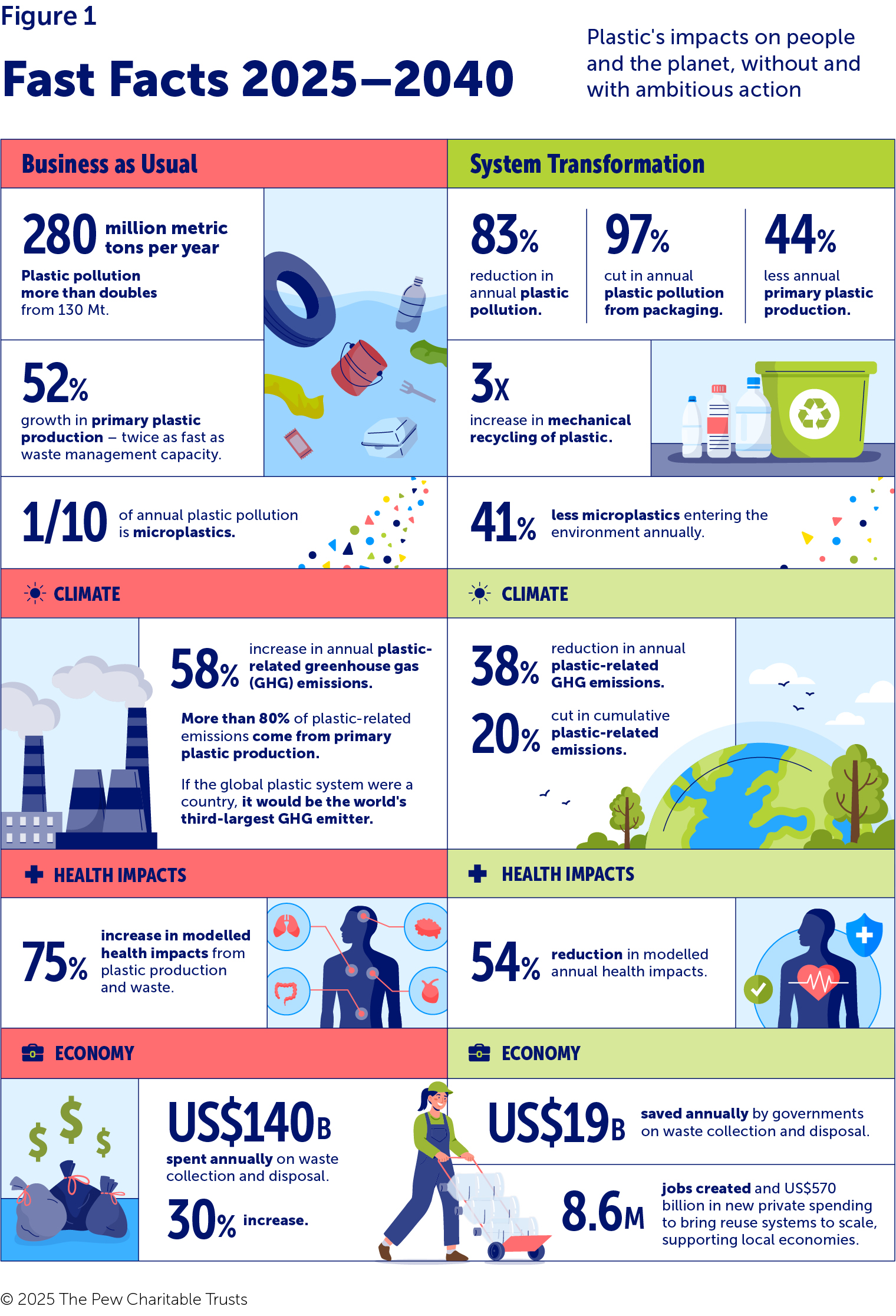

Our analysis also finds that plastic is interconnected with other global challenges, and that solving the plastic pollution problem will have broad implications for improving the health of people, the planet and the global economy. (See Figure 1.) With the added urgency created by five more years of growing plastic pollution, we renew and amplify the call for ambitious action and transformative strategies to address not only plastic pollution but also the far-reaching consequences of the plastic system.

Our assessment of the global plastic problem yielded the following nine key findings:

1. Plastic pollution will more than double over 15 years. As of 2025, 130 Mt of plastic pollutes the environment – land, air and water – each year. Without ambitious global action, that figure will rise to 280 Mt by 2040 – equivalent to dumping nearly a garbage truck worth of plastic waste every second. This increase will be primarily driven by rapidly growing production and use of plastic – particularly in packaging and textiles – that will further overwhelm already inadequate waste management systems.

2. Growth in plastic production will outpace waste management capacity. Absent urgent international efforts, annual primary plastic production will rise 52% from 450 Mt in 2025 to 680 Mt in 2040, growing twice as fast as waste management, which, even with considerable investment, will expand by only 26%. By 2040, annual costs to collect and dispose of plastic would increase by 30% to US$140 billion, requiring additional public funds and posing a financial risk to businesses. Despite this increased spending, the share of plastic waste that is uncollected will nearly double by 2040 from 19% to 34%.

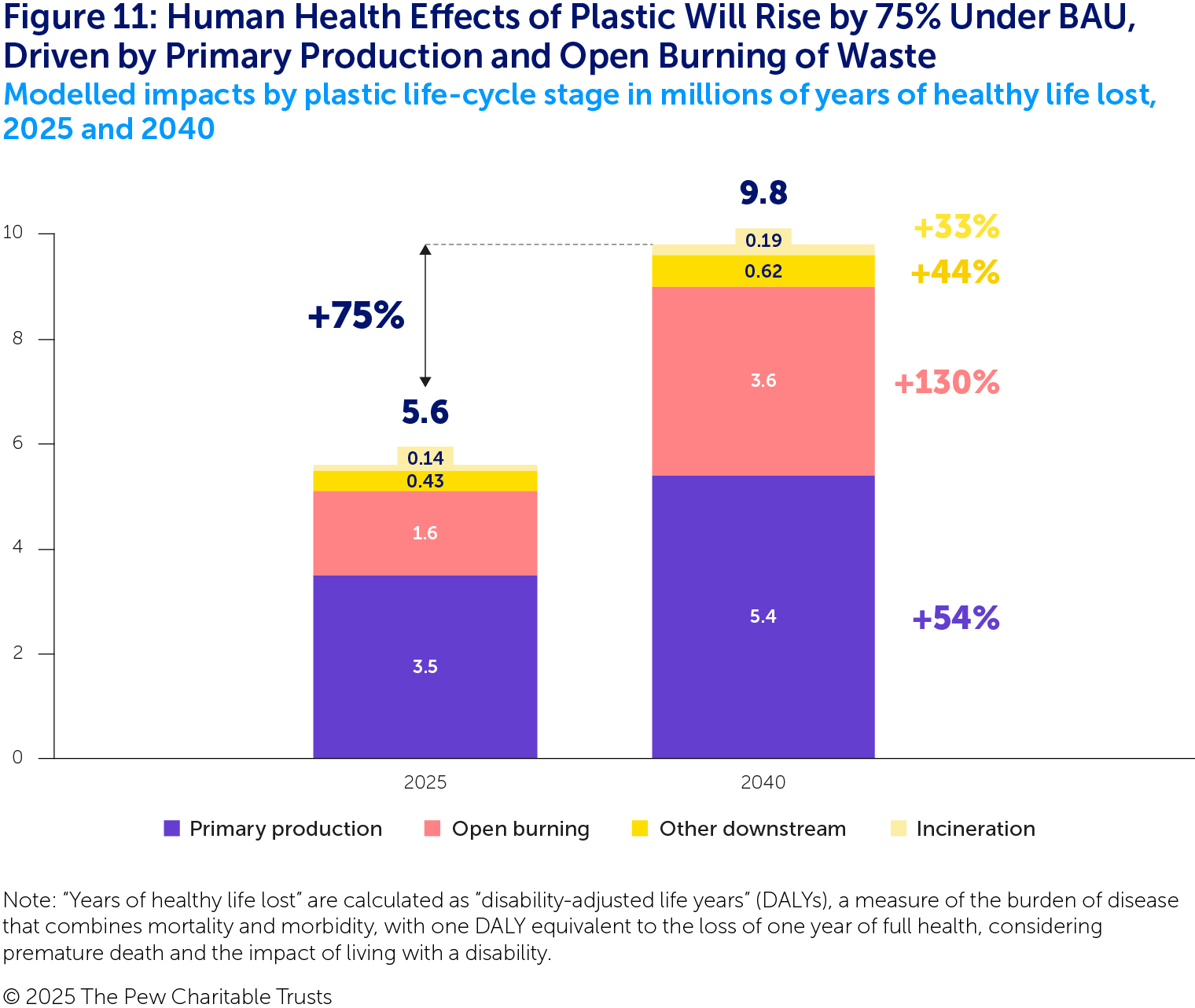

3. Plastic can harm human health at every stage of its life cycle. Barring robust global action, health impacts from plastic production, waste and pollution, before accounting for use, will increase by 75% over the next 15 years, primarily because of new polymer production and open burning, with the most vulnerable communities bearing the brunt.4 A growing number of studies have linked plastic pollution and chemicals used in plastic products to health problems, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, asthma, decreased fertility and cognitive and developmental issues.5 Research has conservatively estimated the annual costs of health effects from plastic chemicals alone to be as high as US$1.5 trillion globally.6 That figure will only grow as plastic production, use and pollution increase, and as understanding of the health impacts expands.

Because of data gaps, we did not include the health impacts of plastic use or microplastics in our analysis, but those effects are likely to be significant, as are the potential human health benefits of reducing plastic use.7 To date, more than a quarter of the more than 16,000 chemicals used in plastic products have been identified as possible sources of harm to human health.8 Among the topics of growing concern are endocrine-disrupting chemicals – which affect the hormones that regulate human health and are widely used in food packaging, cookware, toys and cosmetics – and microplastics, which are increasingly being found throughout people’s bodies and have been linked to potential risks to digestive, reproductive and cognitive function.9

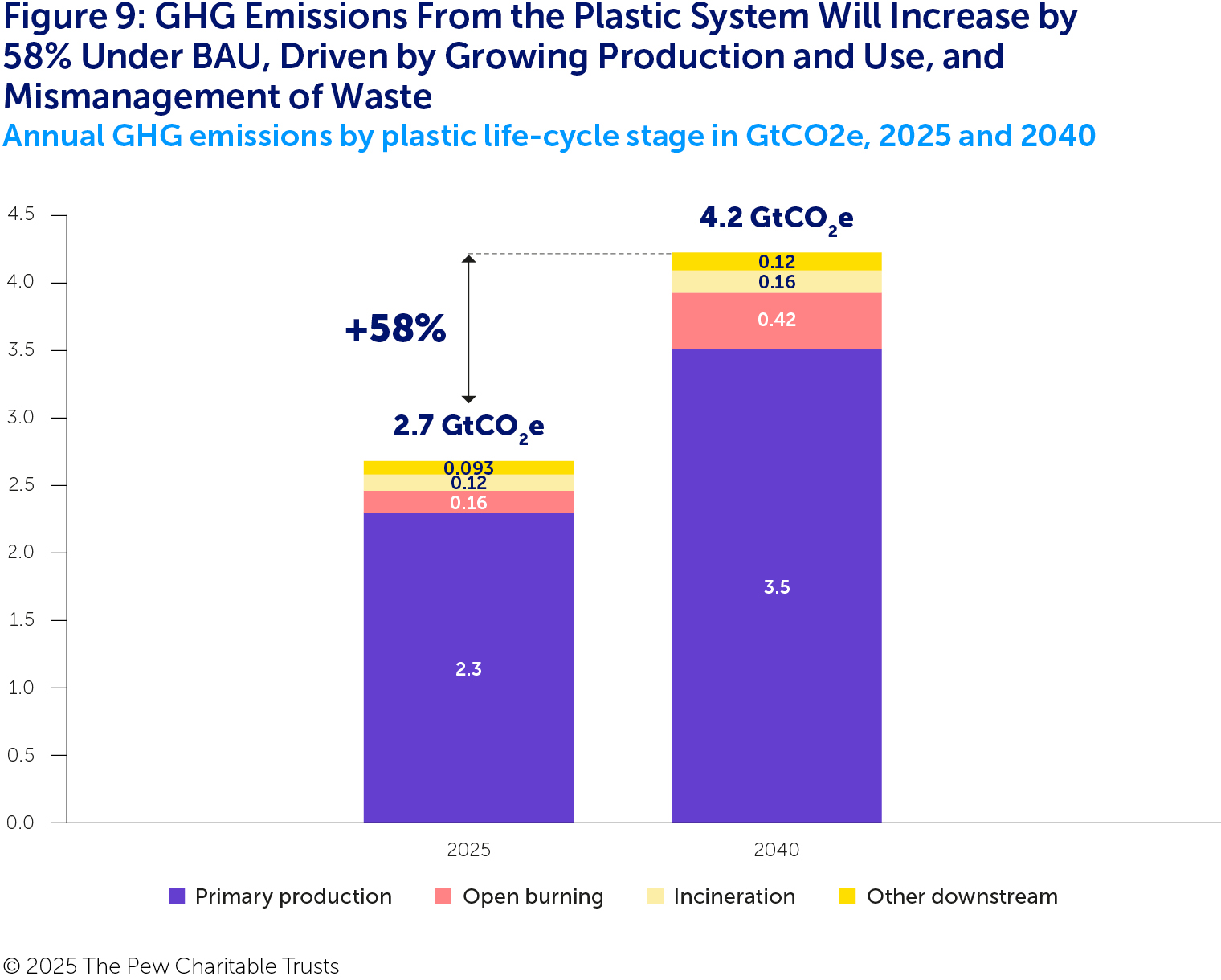

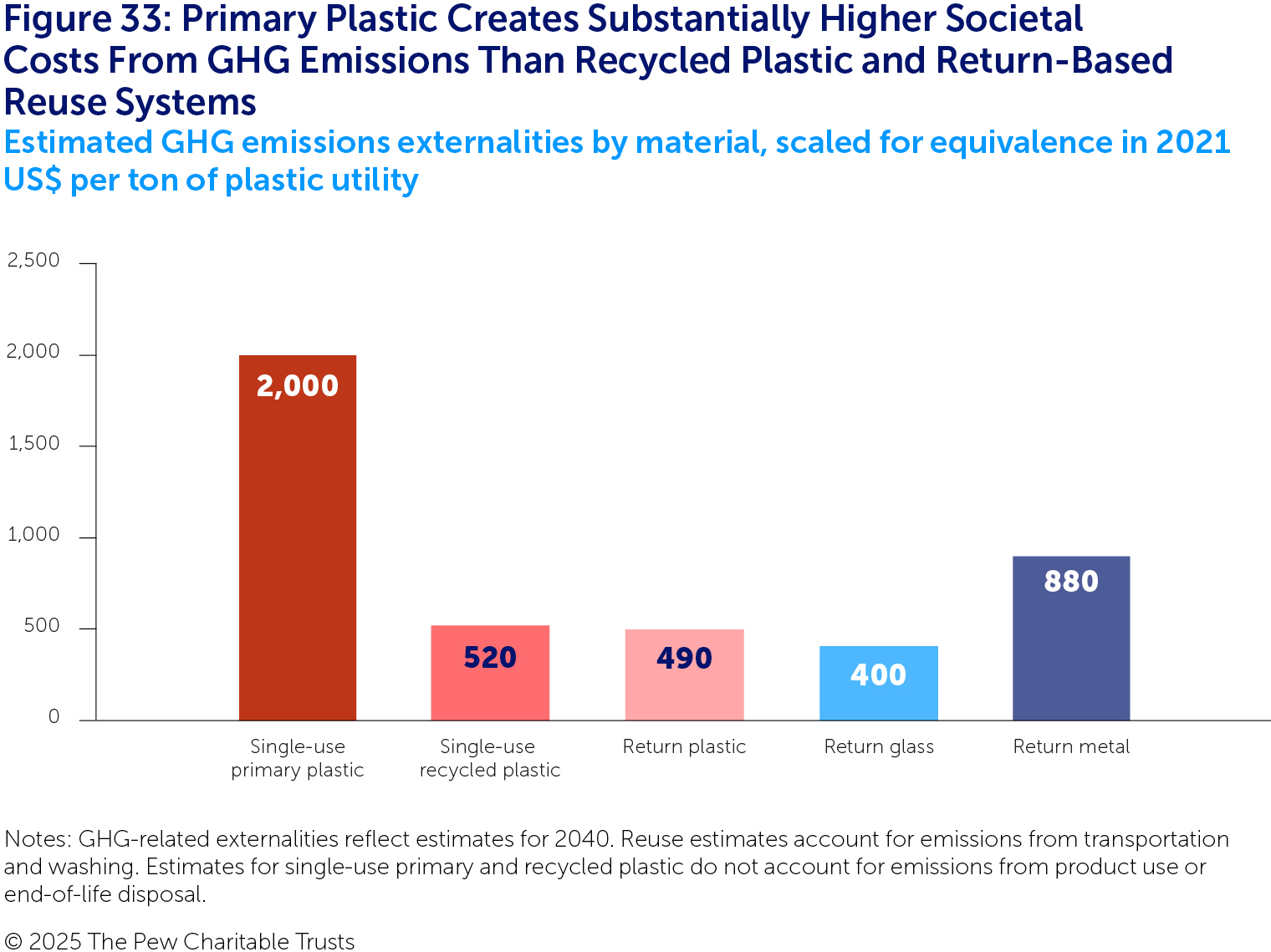

4. Greenhouse gas emissions will surge. Unless the plastic system is transformed, by 2040, annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the global plastic system will increase by 58% to 4.2 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalents (GtCO2e) – a metric used to standardize the measurement of emissions of different GHGs – equivalent to the emissions from one billion gasoline-powered cars.10 Achieving the commitments made by the global community under the Paris Agreement – the legally binding international treaty adopted in 2015, which pledges to keep global temperature rise below 2°C and ideally under 1.5°C – will require rapid declines in annual emissions, especially from plastic production, which accounts for 86% of plastic-associated emissions in 2025.11

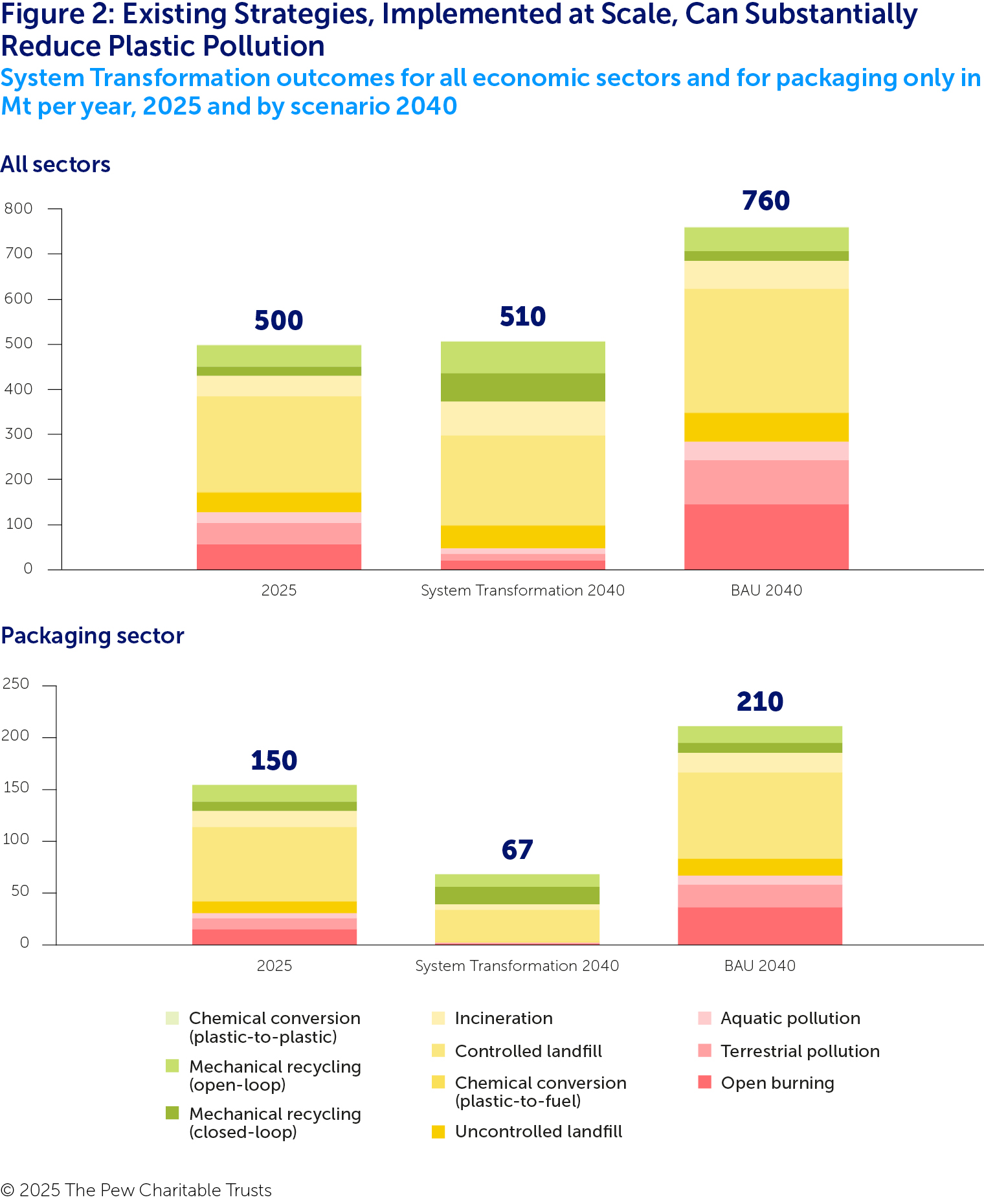

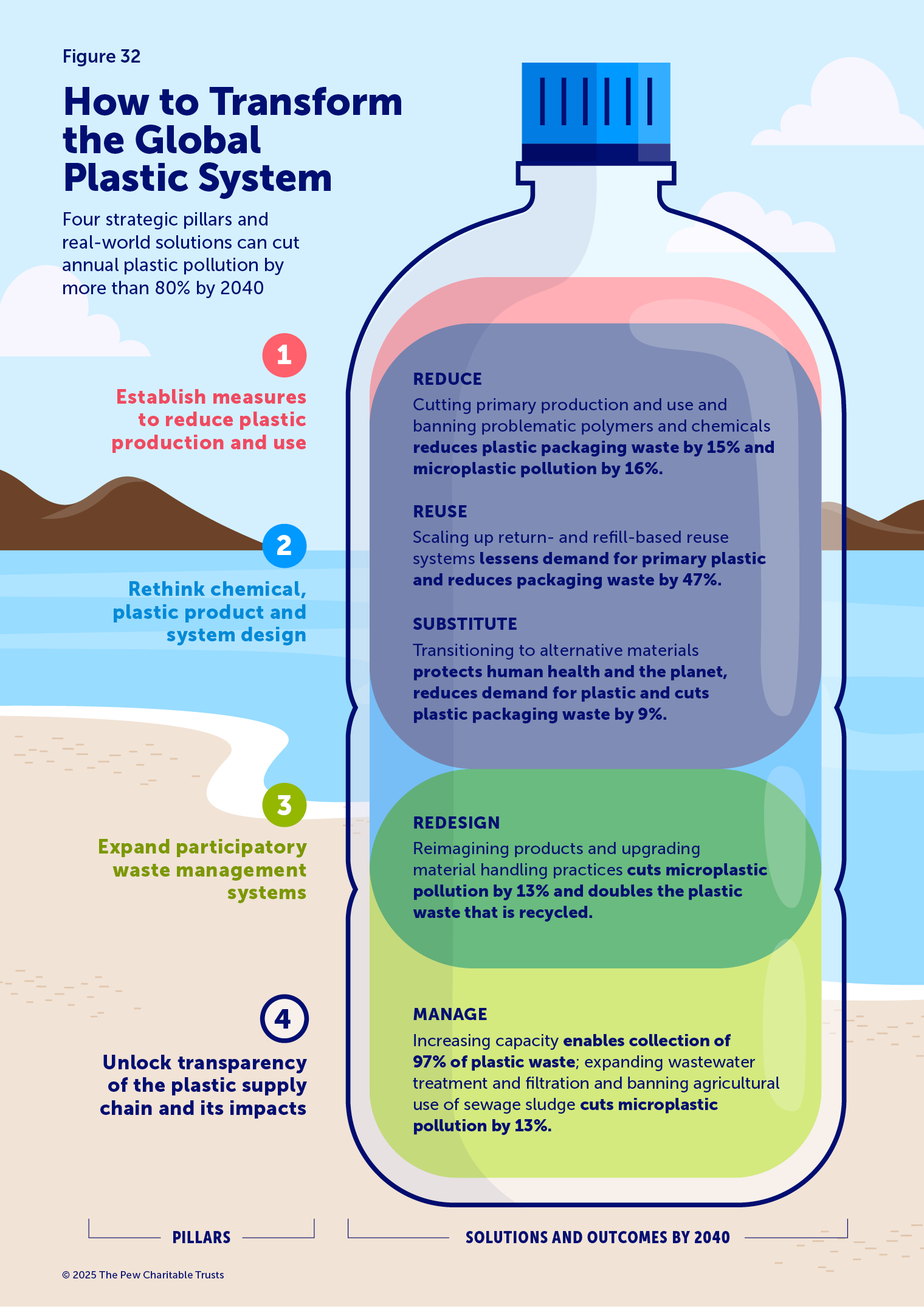

5. Ambitious global action can dramatically reduce pollution. Our “System Transformation” scenario reflects ambitious, complementary actions using existing solutions across the plastic system to cut production and use and improve waste management, which together could reduce annual plastic pollution by 83% by 2040. The myriad benefits of this scenario include lower GHG emissions, reduced harm to human health, as well as more efficient use of public funds and the creation of new business markets and opportunities. This report shows that an integrated approach to plastic that touches all the modelled economic sectors is crucial, with actions needed before, during and after plastic product use. (See Figure 2.)

A key finding from this scenario is the importance of reducing production levels of “primary plastic” – plastic made from raw materials for the first time – to decrease plastic pollution and the impacts of production on human health and climate. The recommended actions could cut annual production of new plastic by 44% by 2040, compared with current projections, achieving a 14% reduction from 2025 levels, all while maintaining the same level of service for consumers and businesses. Reaching these reductions could also unlock new opportunities for sustainable solutions, a market already valued in the trillions of dollars.12

Although implementing and rapidly scaling policies across the plastic life cycle worldwide will require unprecedented global collaboration and commitment, doing so would have substantial benefits, including a 38% reduction in annual GHG emissions from plastic, a 54% reduction in modelled annual health impacts, and a US$19 billion decrease in yearly government spending on plastic collection and disposal by 2040.

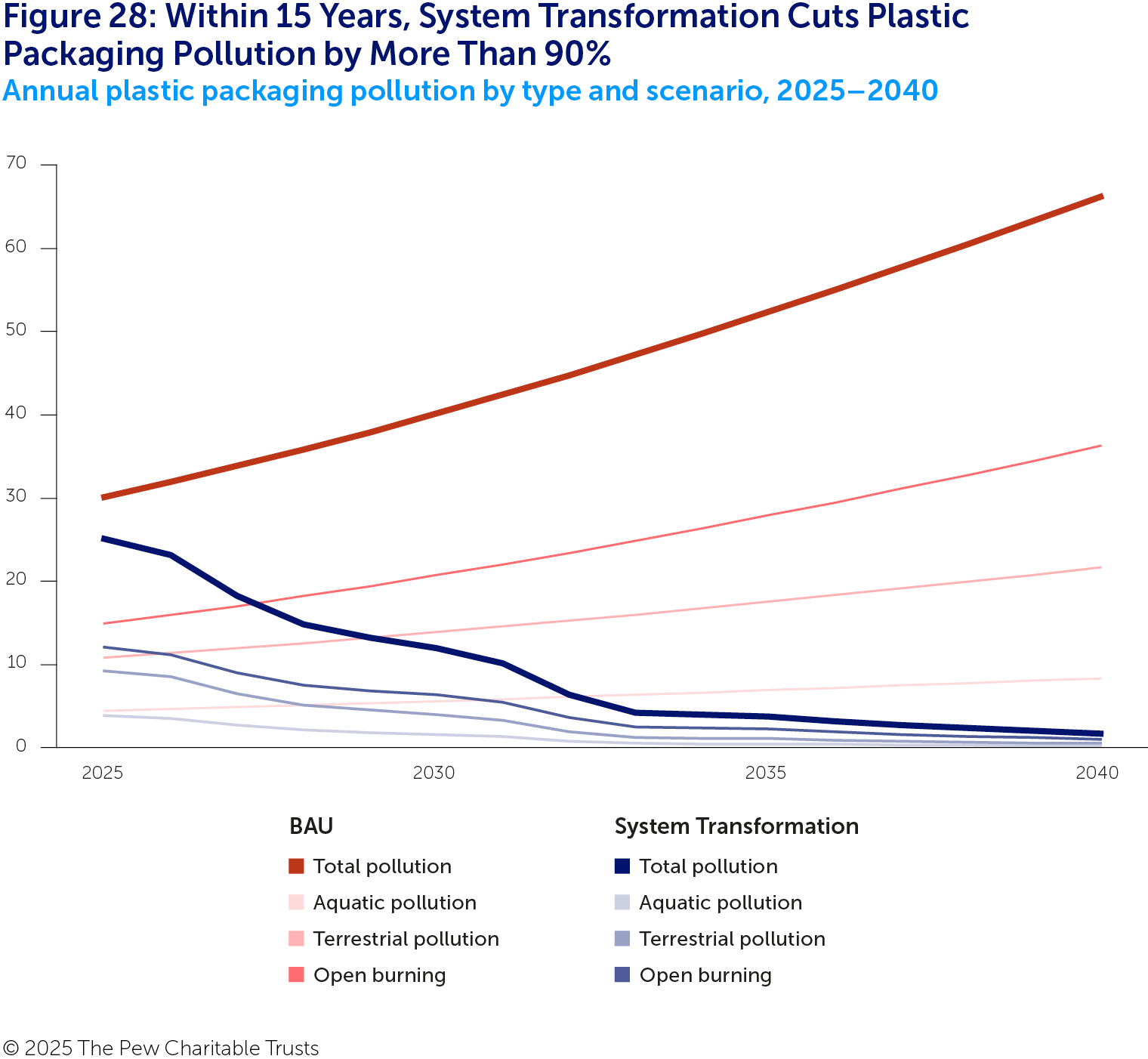

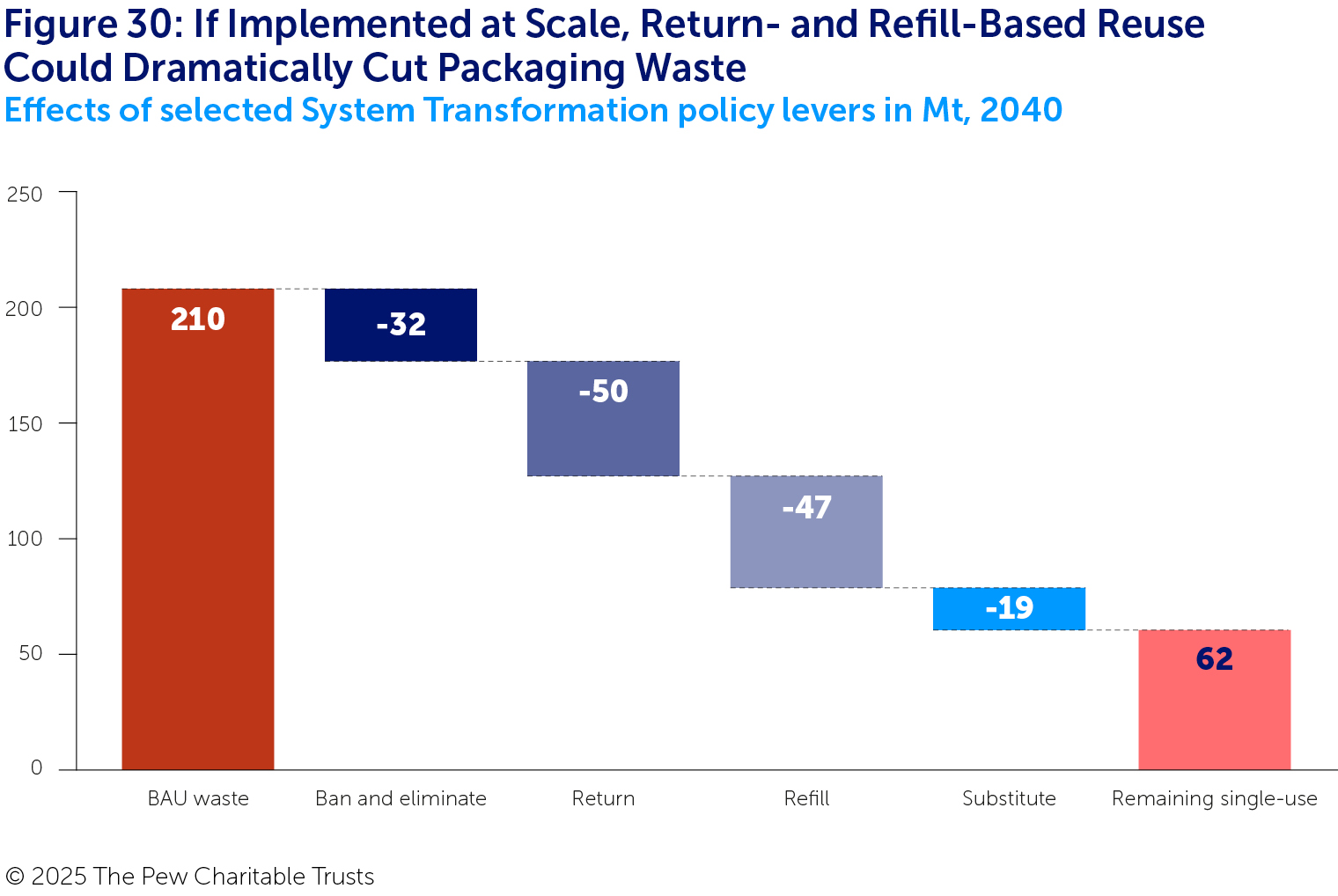

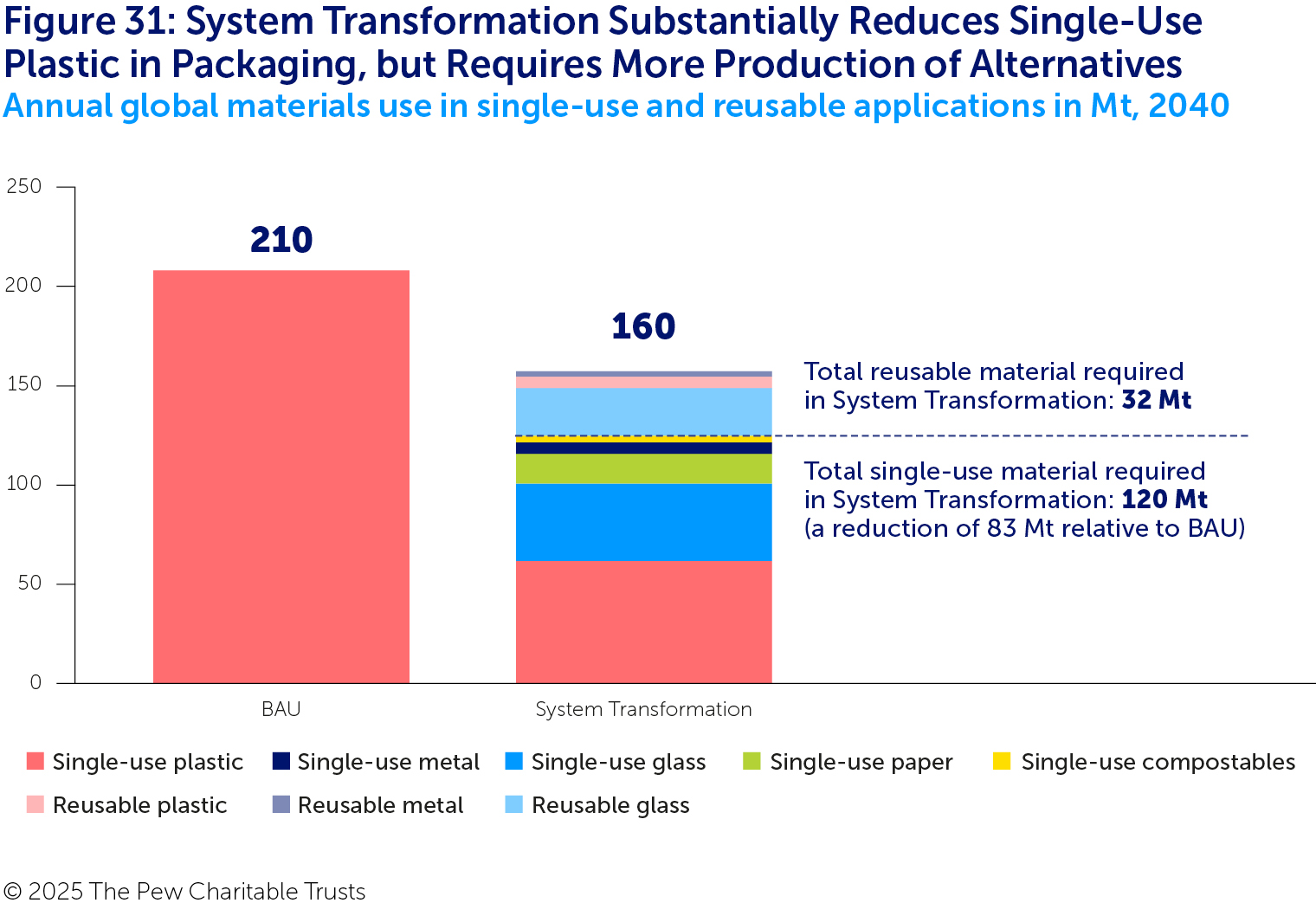

6. Packaging pollution can be virtually eliminated. Pollution from plastic packaging, the largest source of plastic waste, can be nearly eradicated by 2040, decreasing 97% from 66 Mt under BAU to less than 1.7 Mt by 2040. System Transformation could reduce primary plastic production for packaging by 76% compared with BAU and by 66% relative to 2025. Reuse accounts for two-thirds of the total decrease by 2040, demonstrating the central role that reuse will play in transforming how products are delivered and used.

In particular, the scale of reuse required for these reductions will entail shifting nearly US$570 billion in annual private sector spending away from single-use and towards reuse, which highlights the many new economic opportunities that System Transformation presents, especially for early adopters and innovators. These investments would also support other substantial benefits, including 48% lower GHG emissions from packaging production and hundreds of thousands of new jobs.

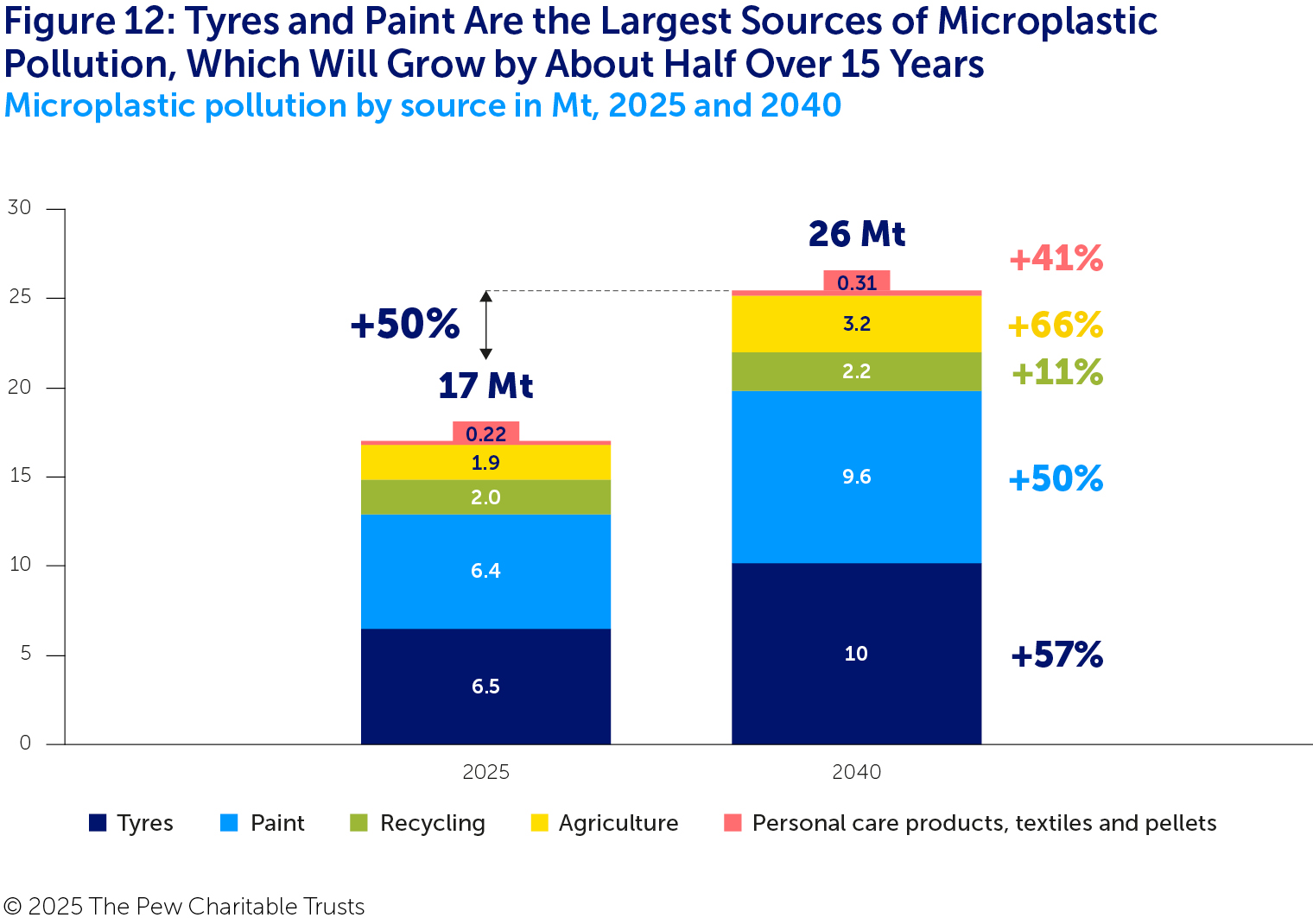

7. Solving microplastic pollution will require innovative solutions. Microplastics make up 13% of global plastic pollution in 2025, with the largest sources being tyre wear and paint (10 Mt each), agriculture (3 Mt) and recycling (2 Mt). Under BAU, microplastic pollution will grow from 17 to 26 Mt annually by 2040. In high-income economies, microplastic pollution will make up 79% of overall plastic pollution by 2040.

By contrast, under System Transformation, the annual flow of microplastics entering the environment could be cut by 41% by 2040 through a suite of actions to reduce production and use, improve product design and scale solutions for capture and treatment of microplastics. Although these targeted policy actions can achieve meaningful reductions in microplastic pollution, more than half of it remains unaddressed. This limitation highlights the need for other innovative solutions to deliver more substantial decreases in microplastic pollution.

8. System Transformation offers opportunities for workers and communities. Reimagining the plastic system would support 8.6 million additional jobs and create new business opportunities. But in the near term, it would also have consequences for millions of people worldwide whose livelihoods will require dedicated attention as the new plastic economy takes shape. Effective policies to tackle plastic pollution can create jobs, help alleviate poverty and safeguard the well-being of the world’s most vulnerable people.

More than three-quarters of all plastic that is recycled globally is collected and sorted by waste pickers, most of whom are from marginalized parts of society.13 Our analysis shows that waste pickers could make up nearly two-thirds of the plastic workforce by 2040. Despite providing an important service, these workers are not paid fairly or properly recognized for their contributions and are often exposed to hazardous conditions.14 Participatory approaches to waste management and governance that provide waste pickers with safe working conditions and economic opportunities and fully integrate them into broader waste management improvement strategies will be key to ensuring that the plastic system’s transition is equitable and aligned with efforts to address global poverty.

Furthermore, a shift away from linear economic models, based on production, use and disposal, and towards circular models that prioritize reusable and repairable products will shift the landscape of jobs across the plastic system. Under System Transformation, production accounts for 19% of plastic sector jobs by 2040, down from 30% under BAU, recycling jobs increase by 39% from 2025 to 2040 and expanded reuse systems create nearly 620,000 new jobs by 2040. Additional opportunities may also arise from thoughtful integration of waste pickers – who already play a substantial role in the recycling economy – as part of future waste management and reuse systems. Applying waste pickers’ knowledge and expertise could facilitate a successful and socially responsible transition.

9. Delay is costly. Waiting just five years to initiate System Transformation would result in 1,100 Mt more primary plastic being produced, 540 Mt more plastic entering the environment and 5.3 GtCO2e more GHG emissions between 2025 and 2040. A five-year delay would increase governments’ annual costs for plastic collection and disposal by an estimated 23% annually (US$27 billion) and add US$6.1 billion in annual capital expenditures by 2040 for open-loop mechanical recycling and incineration capacity for plastic alone. But these technologies also would be at growing risk of obsolescence as the economy becomes more circular. So this same five-year delay could lead to overinvestment in solutions that do not align with the future plastic system and, in turn, sizeable financial losses for companies and inefficient use of the limited public funding available for addressing the global plastic problem.

Opportunities for policymakers, researchers and businesses

The global community can make significant strides towards eradicating plastic pollution by 2040, despite the slow progress to date, by using existing solutions to transform the global plastic system, making ongoing investments in innovation and adopting a renewed sense of urgency. Although this is a sizeable challenge, the opportunities are substantial. Transforming the global plastic system will provide workers with better jobs and working conditions and build the business models of the future – ones that are built on sustainability and fostering innovation to provide better-designed materials and products.

This amount of system-level change will require coordinated action by policymakers, businesses and researchers to tackle the foundational challenges that hinder progress – rebalancing manufacturing, design, governance and consumer decisions to prioritize people and the environment. This report outlines four strategic pillars with associated opportunities for government, the research community and business to achieve this lofty goal:

1. Establish measures to reduce plastic production and use.

- Implement policy measures to ensure that market prices reflect the true costs of plastic and other materials.

- Complement pricing measures with targeted policies to reduce plastic production and use to sustainable levels, such as eliminating subsidies, enacting reduction targets and restricting new production facilities.

- Phase out low-utility, avoidable plastic through bans, product design standards and voluntary corporate actions to reform supply chains.

2. Rethink chemical, plastic product and system design.

- Adopt pre-market policies that assess the safety of chemical additives used in plastic, to safeguard human health and the environment.

- Establish and enforce a list of comparatively safer chemicals to promote material innovation and product safety.

- Implement policies that support the shift from single-use to reusable products, such as targets, standards, investment in shared infrastructure and financial incentives for consumers and businesses.

- Establish consistent product design requirements and standards for safe reuse and recycling and to reduce microplastic emissions.

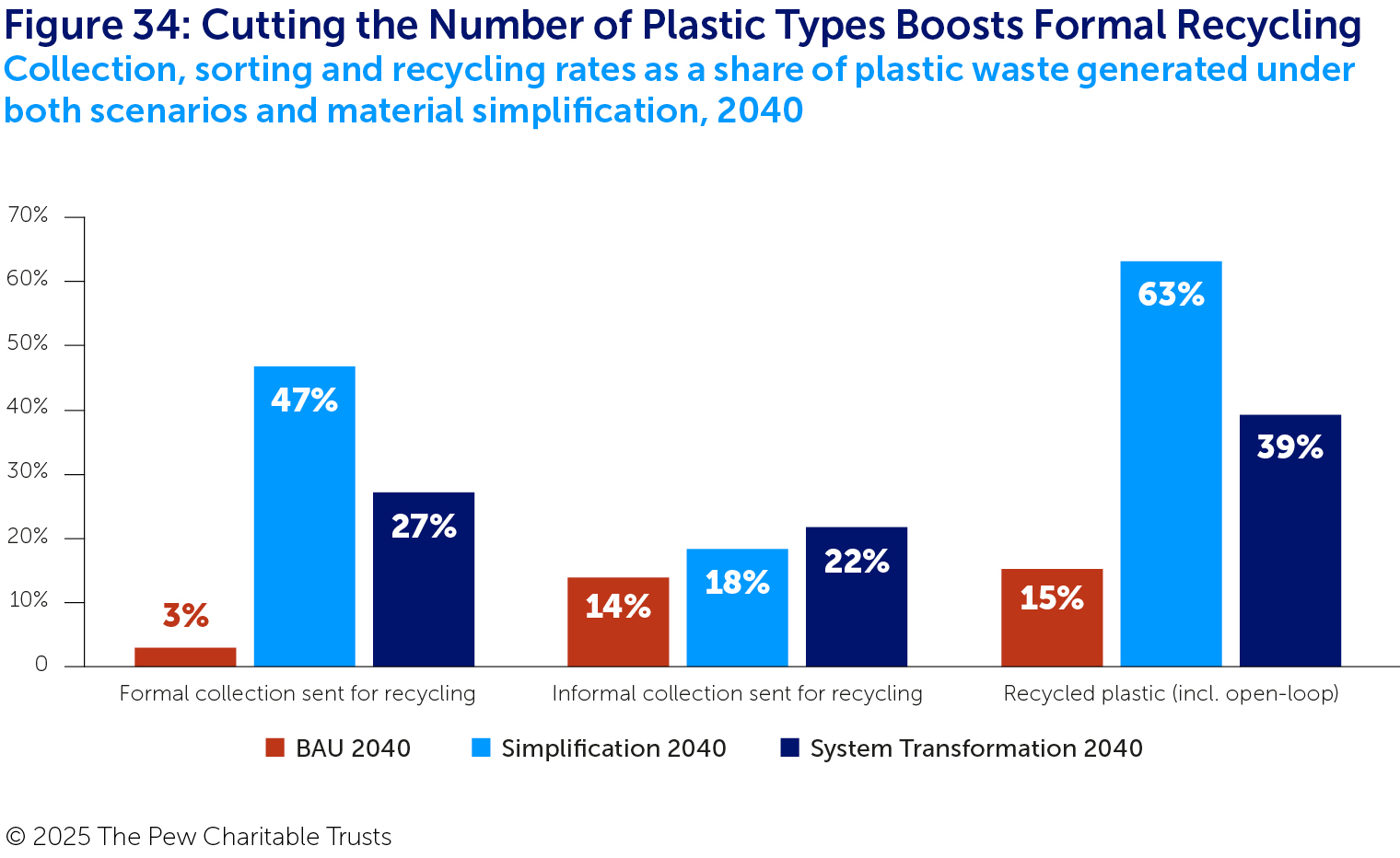

- Simplify polymers and polymer compositions, such as by restricting problematic polymers – those that are difficult to recycle or pose health risks.

- Adopt measures to reduce microplastic shedding across key sectors, including plastic production, recycling, agriculture, marine, textile, transport and construction.

- Promote innovation in sustainable materials development, promising recycling technologies and reusable products.

- Establish public-private partnerships and provide incentives for open and transparent collaborations across industries to accelerate development of innovative solutions.

3. Expand participatory waste management systems.

- Implement policies to scale waste collection, including collection and recycling targets, deposit return schemes, design and labelling standards and, where appropriate, increased separate collection.

- Expand environmentally sound waste management systems by integrating waste pickers and other informal workers into waste management planning and extended producer responsibility (EPR) schemes to finance waste collection and management.

- Incorporate informal workers into census protocols to improve understanding of their contributions to existing waste management and improve long-term strategies.

- Develop targeted funding for groups that lack access to traditional financing to create cooperatives, offer training opportunities and support participation in governance.

- Establish enhanced filtration at recycling and wastewater facilities to minimize microplastic leakage to the environment and identify long-term, safe disposal options for contaminated waste sludge.

4. Unlock transparency of the plastic supply chain and its impacts.

- Invest in research into and monitoring of the impacts of the global plastic system, particularly on human health.

- Develop targeted research into impacts of exposure to plastic on vulnerable populations, including communities adjacent to production and waste management facilities, waste pickers and workers across the plastic supply chain.

- Disclose data on plastic-related commerce, impacts, risks and opportunities through reporting platforms, such as CDP.

- Establish a global chemical reporting and disclosure framework to help improve supply chain transparency, evaluate chemical risks and assess progress towards global targets.

- Increase interdisciplinary research and monitoring to provide a fuller picture of the extent of the plastic system’s environmental and health impacts.

Urgent action is needed to transform the global plastic system and curb the worst effects of plastic pollution on the environment and human health, and to ensure efficient use of financial resources. A coordinated, ambitious effort by the global community can substantially reduce plastic pollution overall and virtually eliminate pollution from plastic packaging in the next 15 years, while reducing costs, supporting millions of jobs and bolstering efforts to protect human health, address climate change and alleviate poverty.

Introduction

In 2020, humanity crossed an ominous tipping point: For the first time, the total mass of all human-made objects – totalling 1.2 trillion metric tons – surpassed the total biomass of all living things on Earth.15 And humanity only made the vast majority of all that human-made mass, including all of the billions of tons of plastic, in the past 100 years. Although plastic is still a relatively novel material – having only existed for about 80 years – it has become ubiquitous, with production growing from 2 Mt in 1950 to nearly 500 Mt in 2025.16

Among human-made materials, plastic’s low cost, light weight, durability and other attractive properties have led to its proliferation across every sector of the world economy.17 Plastic is credited with enabling expansion of people’s access to clean drinking water, medical supplies and cost-effective food, and with substantial improvements in automobile fuel efficiency, renewable energy technologies and reduced GHG emissions through reduced product weights across many sectors.18

Yet the same qualities that have delivered plastic’s many benefits have also led to pollution on an unprecedented scale. The elimination of plastic pollution is an era-defining global challenge.

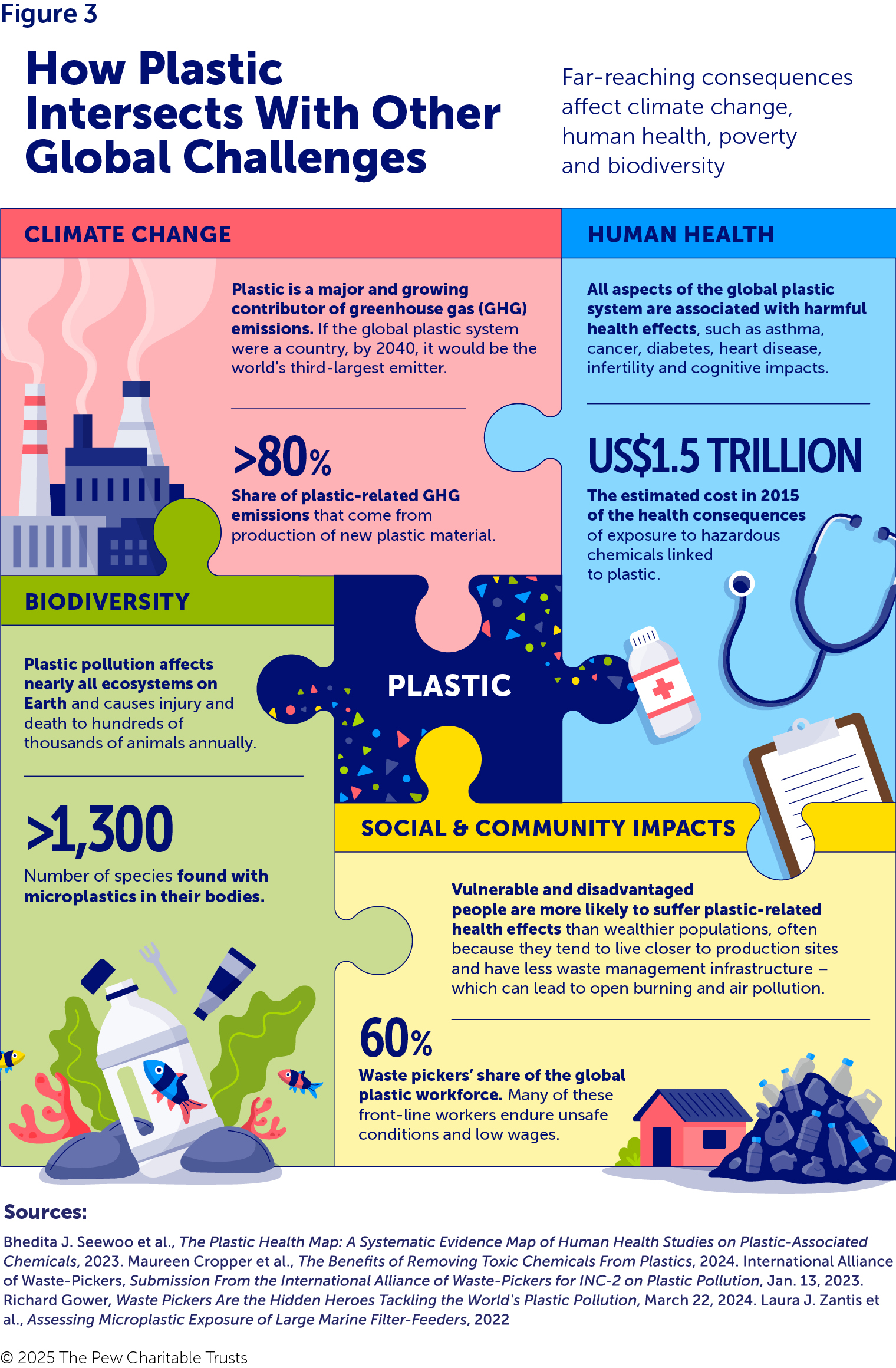

How is plastic connected to other global challenges?

Despite the promise of greater sustainability, the world's predominately linear "take-make-waste" economy and the low cost of plastic have stymied progress towards more thoughtful design and a circular “reuse, repair and recycle” economic system of products and materials.19 Efforts to achieve sustainability must extend beyond simply more efficient use and recycling of materials or more circular business models to reduce overall plastic production; business demand for plastic; and the impacts of plastic and its associated chemicals on biodiversity, climate change, human health and the world economy.20 (See Figure 3.)

In recognition of plastic’s wide-ranging implications for people and the planet, this report builds on the model and analyses developed in BPW1, provides a first-of-its-kind scenario-based analysis of the human health effects of plastic at a global scale and offers some of the first estimates for microplastic generation from agriculture and paint. With these more expansive analyses, we aim to deepen the evidence base for decision makers across government, business, civil society and academia as they respond to the plastic problem, evaluate trade-offs and implement solutions.

Climate change

Primary plastic production accounts for more than 80% of GHG emissions from across the plastic life cycle, reflecting the high carbon generation from two key parts of the plastic production process: chemical manufacturing and fossil fuel extraction.21 This makes the plastic industry particularly challenging to decarbonize (i.e., to reduce or eliminate GHG emissions from industrial and other processes), which will be essential to meeting the ambitious global GHG emissions targets in the Paris Agreement. Should production continue to increase at current rates, annual GHG emissions from plastic would triple by 2050 from 2019 levels, accounting for nearly one-third of the global carbon budget – the total amount of GHG emissions allowable to keep long-term planetary warming within 1.5°C.22

These emissions also undermine the meaningful contributions that plastic has made to decarbonization in other areas of the global economy, particularly as a light weight and flexible material that requires less energy to transport than heavier options – and so generates fewer emissions during shipment – and has enabled important innovations in renewable energy technologies.

Human health

Research into specific health outcomes associated with human exposure to plastic is nascent and ongoing, but early findings indicate that every stage of the plastic life cycle has human health implications. Plastic products contain more than 16,000 intentionally added chemicals as well as myriad unintentionally added contaminants.23 Studies have already linked many of these chemicals to a range of health effects, such as hormone disruption, decreased fertility, low birth weights, cognitive and other developmental changes in children, diabetes and increases in cardiovascular and cancer risk factors.24

What Are Plastic Products Made Of?

Plastic is a type of organic polymer, meaning it is made up of various monomers – certain types of small molecules.25 As part of the plastic production process, manufacturers add a range of chemicals, such as solvents, catalysts or lubricants, called processing aids that facilitate reactions among the monomers and polymers. Other additives impart or enhance functions in the plastic itself, including plasticizers to improve flexibility, flame retardants for fire resistance, antioxidants to slow or prevent decay from contact with oxygen and colorants to add pigments. Non-intentionally added substances are another set of chemicals that can also be present in plastic, usually resulting from chemical by-products or breakdown or from contaminants introduced during manufacturing of the polymer or product. These additives and non-intentionally added substances can be released during the plastic life cycle, putting humans and the environment at risk.

People can be exposed to potentially harmful chemicals when plastic materials and products are produced, while using plastic products and when those products become waste and are recycled or disposed of. These dangers are especially acute for communities located near facilities that produce, manufacture, recycle and dispose of plastic, as well as for workers at those sites. These exposures can disproportionately affect women, children and underprivileged populations and have been found to increase risks of asthma, childhood leukaemia, cardiovascular disease and lung cancer.26 Despite these risks, fewer than 6% of the known plastic-associated chemicals are subject to any form of regulation globally.27

Another area of concern is the continued proliferation of microplastics in the environment and, increasingly, in human bodies.28 Early research points to potential risks to digestive systems, including cancer, and to reproductive systems.29

Social and community impacts

Transitioning away from plastic use where feasible and appropriate will require participation and buy-in from all sectors of society to understand and address the potential follow-on effects of system change. As part of these efforts, decision makers will need to consider several key segments of society to ensure that the transformation of the plastic system aligns with global endeavors to tackle broader social challenges:

“Fenceline communities” are populations situated adjacent to high-polluting industrial facilities that often bear the brunt of the health and social impacts from those operations.30 Estimates suggest that these communities house at least 50 million people worldwide, predominately from low-income and other marginalized populations.31 One study of six countries found that lung cancer risk was 19% higher in fenceline communities near petrochemical plants than in the general population.32

Waste pickers are informal workers who collect, sort and sell materials for recycling or reuse and are responsible for approximately 60% of plastic recycling globally.33 They are a key segment of the global “informal sector” that plays a critical role in managing waste and that millions of people rely on for their livelihoods.34 But despite waste pickers’ significant contributions, their role is largely unrecognized. Many face hazardous working conditions and receive low wages.35

Biodiversity

The alarming and highly visible impacts on marine life first brought the problem of plastic pollution’s effects on biodiversity into the public consciousness. And more recent research offers no less cause for concern. Plastic pollution affects almost every species group in the ocean, from turtles, seabirds and mammals to the plankton that underpin the marine food web.36 Scientists have identified a new fibrotic disease in seabirds called “plasticosis” characterized by inflammation and scar tissue in the digestive tract resulting from ingestion of plastic; other effects of ingestion can include intestinal blockage, organ damage and mortality.37

Further, although global figures for entanglements in abandoned, lost and discarded fishing gear – collectively known as “ghost gear” – are hard to come by, they are estimated at roughly 136,000 seals, sea lions and large whales killed every year.38

Concerning impacts of plastic pollution on biodiversity are also emerging on land and in freshwater environments – affecting soil, organisms, plants and even livestock, with microplastic pollution potentially affecting food crops.39 In fact, although research on plastic pollution in terrestrial ecosystems is still emerging, recent studies estimate the total stock of microplastic debris in the top metre of soil worldwide at between 1.5 and 6.6 Mt which are one and two orders of magnitude, respectively, greater than the estimated microplastic stock at the ocean surface.40

A changing policy landscape

In the five years since BPW1 was published, a clear scientific consensus has emerged that no or delayed action to combat plastic pollution would have severe consequences for people and the planet.41 The U.N. plastics treaty negotiations, initiated by U.N. Environment Assembly resolution 5/14 in 2022, could provide a pathway towards ending plastic pollution.42 But to date, negotiations are ongoing, with political differences remaining on key elements.

Meanwhile, national and regional policy initiatives have continued and even accelerated, with governments enacting at least 200 new measures from 2020 to 2023.43 Additionally, policy efforts have increasingly shifted away from a narrow focus on single-use plastic bags and towards single-use plastic broadly.44 Further, India, the Philippines, the United Kingdom, the European Union, and multiple U.S. states have enacted new EPR policies for plastic packaging.45 And, in 2024, the EU adopted its ambitious Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation, which, among other things, requires that all packaging be recyclable by 2030; restricts certain single-use plastic, such as for pre-packed fruits and vegetables; sets goals for reusable beverage containers and refills; and limits per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in packaging.46

Overall, however, policies and business actions still tend to be narrowly focused and have not adopted the full life-cycle approaches emphasized in BPW1 and other studies.47 Microplastics continue to be underrepresented in policy efforts (although new measures on tyres, pellets and textiles are being adopted and implemented in the EU), and in most cases, policies do not consistently consider the broader implications of plastic pollution on people, nature or the climate.48 The political, economic and behavioral inertia built into the existing linear economy plays a big role in stymieing the broader policy discussions that could meaningfully challenge the status quo.49

Against this backdrop of evolving but still insufficient policies at all governmental levels, this report seeks to help embed the broader impacts of plastic into decision-making and to support policymakers and businesses as they weigh plastic’s role in the economy of the future.

This project builds on the work of BPW1 – a global scenario analysis of plastic flows and pollution resulting from municipal solid waste – to incorporate new data, provide a more comprehensive analysis of the sources and impacts of plastic pollution and enable deeper evaluation of policy interventions. This report expands the scope of economic sectors, plastic types and life-cycle stages modelled, accounting for plastic production and use as well as waste management stages and end-of-life outcomes. It also assesses climate, economic and human health effects linked to the plastic life cycle and includes modelling of alternative materials, supporting evaluation of the trade-offs involved in substituting these materials for single-use plastic. For more discussion of the modelling approach, see Appendix B.

In contrast to BPW1, in this report, we define plastic pollution as the mass of macro- and microplastics that enter terrestrial and aquatic environments and the mass of macroplastics that is disposed of through “open burning” – in which plastic waste is burnt in uncontrolled fires either for heat or as waste management – resulting in air pollution.50

Modelled scenarios

For this report, we analysed two scenarios for global plastic pollution from 2025 to 2040. For more detail on data sources and assumptions, see Appendices B and C.

Business as Usual

BAU estimates annual plastic production, use, waste management and end-of-life fates in the absence of additional policy measures to reduce plastic pollution. And it assumes that waste management for macroplastics – including for collection and sorting, recycling and managed disposal – is constrained by expected limitations in capacity growth (i.e., waste management capacity increases roughly in tandem with population or per capita gross domestic product [GDP]). For microplastics, BAU assumes different rates of pollution growth by source, with the mass of microplastics from pellets, recycling, agriculture and textile production derived from the macroplastic modelling.

System Transformation

System Transformation explores the impacts of policy levers targeting macroplastic production, use and waste management. The included policies are either currently under consideration in national, regional and global contexts – including by the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution, the body responsible for crafting the text for a U.N. plastics treaty – or have been examined in previous studies.51

Business as Usual: An untenable trajectory

The world is not on a path towards stopping the escalating tide of plastic pollution. Without action, global plastic production will increase at rates that substantially outpace the growth of an already overburdened waste management system. This, in turn, will lead to a rapid increase in plastic pollution that will pose a growing threat to human health, biodiversity and efforts to reduce global GHG emissions; disproportionately affect marginalized communities; and exacerbate vulnerabilities for millions of people working in the informal waste management sector and living in fenceline communities.

All figures in this chapter are projections based upon our modelling, unless otherwise cited.

All plastic types

Business as Usual will cause annual plastic pollution to more than double from 2025 to 2040

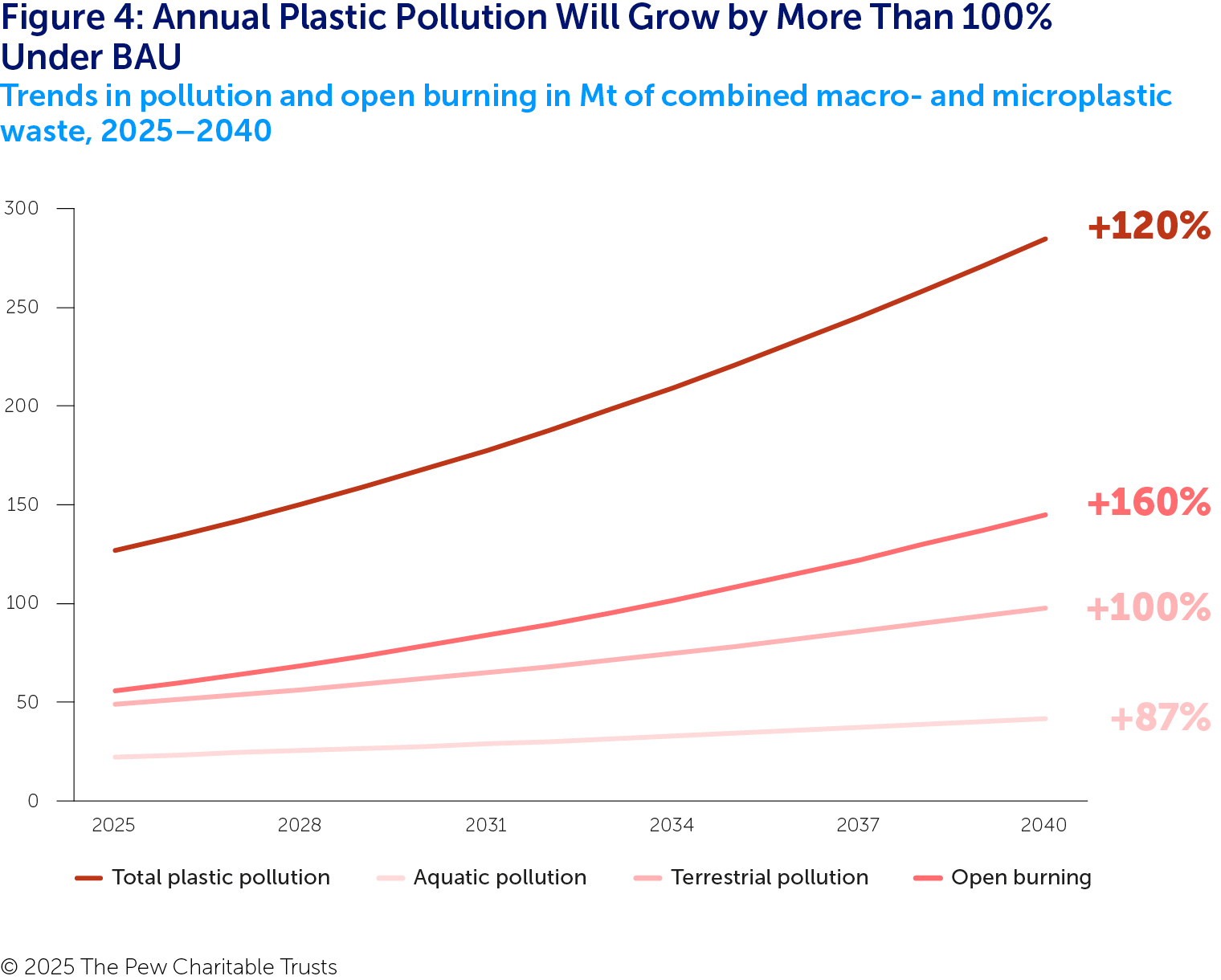

Under BAU, annual plastic pollution jumps from 130 Mt per year in 2025 to 280 Mt in 2040. (See Figure 4.) This rapid growth will harm human health and livelihoods through increased levels of land, water and air pollution, exposure to toxic chemicals, and risk of disease, and lead to higher rates of ingestion and entanglement among other species, resulting in more animals suffering illness, injury and death.

Rising production and use, coupled with an overburdened waste management system, are the main causes of growth in plastic pollution

The doubling of plastic entering the environment under BAU is driven mainly by rapidly increasing production and use of plastic across all sectors worldwide as well as a widening gap between the scale of plastic waste generated and the capacity of waste management systems.

Global annual primary plastic production will rise by 52% under BAU, from 450 Mt in 2025 to 680 Mt in 2040, but waste management capacity will expand by only 26%, despite considerable investment. Upper-middle- and high-income economies account for nearly 80% of global virgin plastic production in 2025, and they will continue to dominate production in 2040. Production in lower-middle- and low-income economies, while still substantially below that in higher-income economies, will more than double between 2025 and 2040.

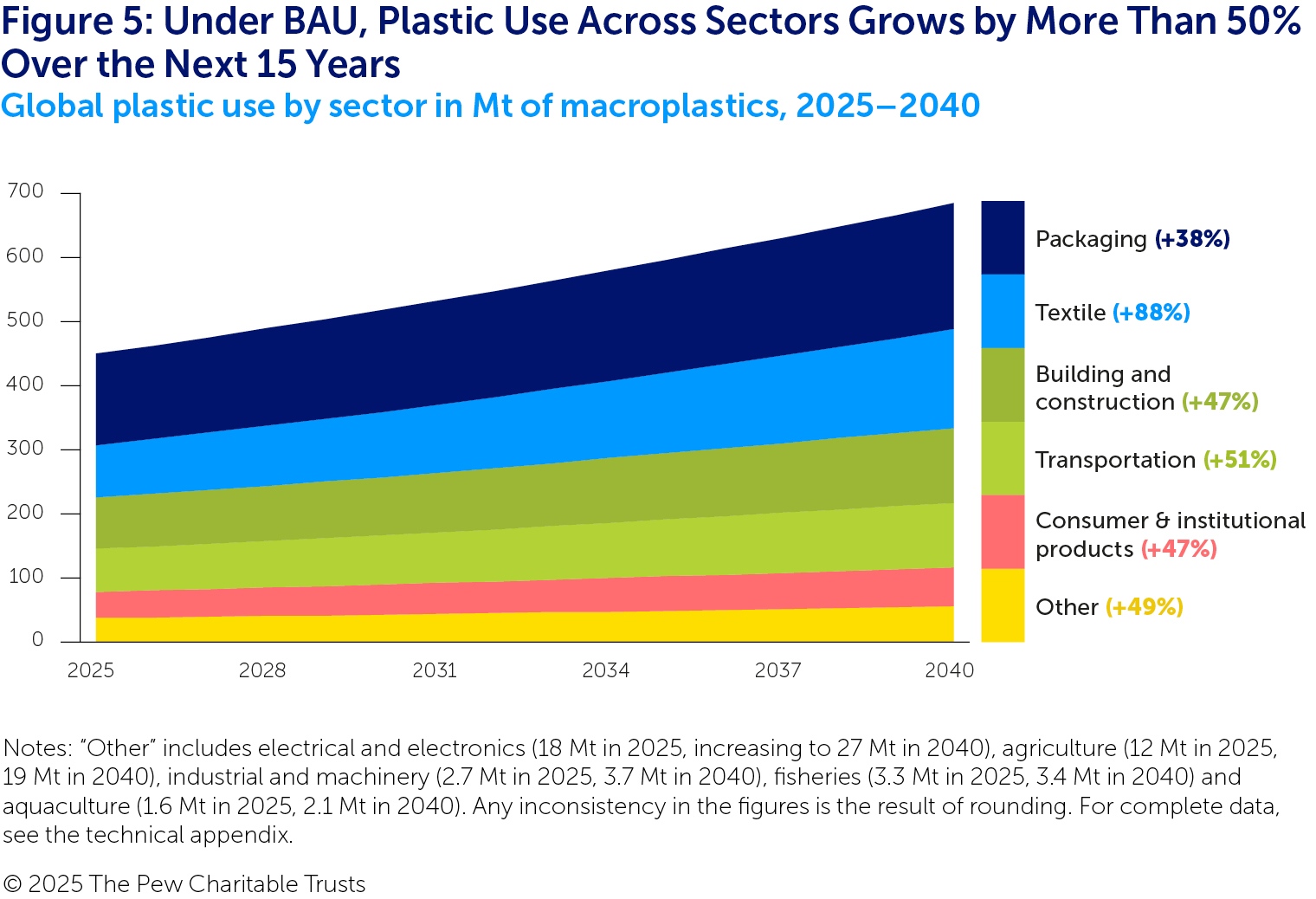

Primary plastic use also increases across all sectors under BAU, driven by plastic’s low cost, light weight and versatility compared with other materials. (See Figure 5.) The packaging sector uses more primary plastic than any other sector in 2025 and will continue to do so in 2040, while the textile sector will have the largest growth in plastic use as the ongoing “fast fashion” trend spurs a proliferation of low-cost, synthetic fabrics.52 Under BAU, the use of plastic in sectors such as transportation and building and construction will also rise, but more slowly.

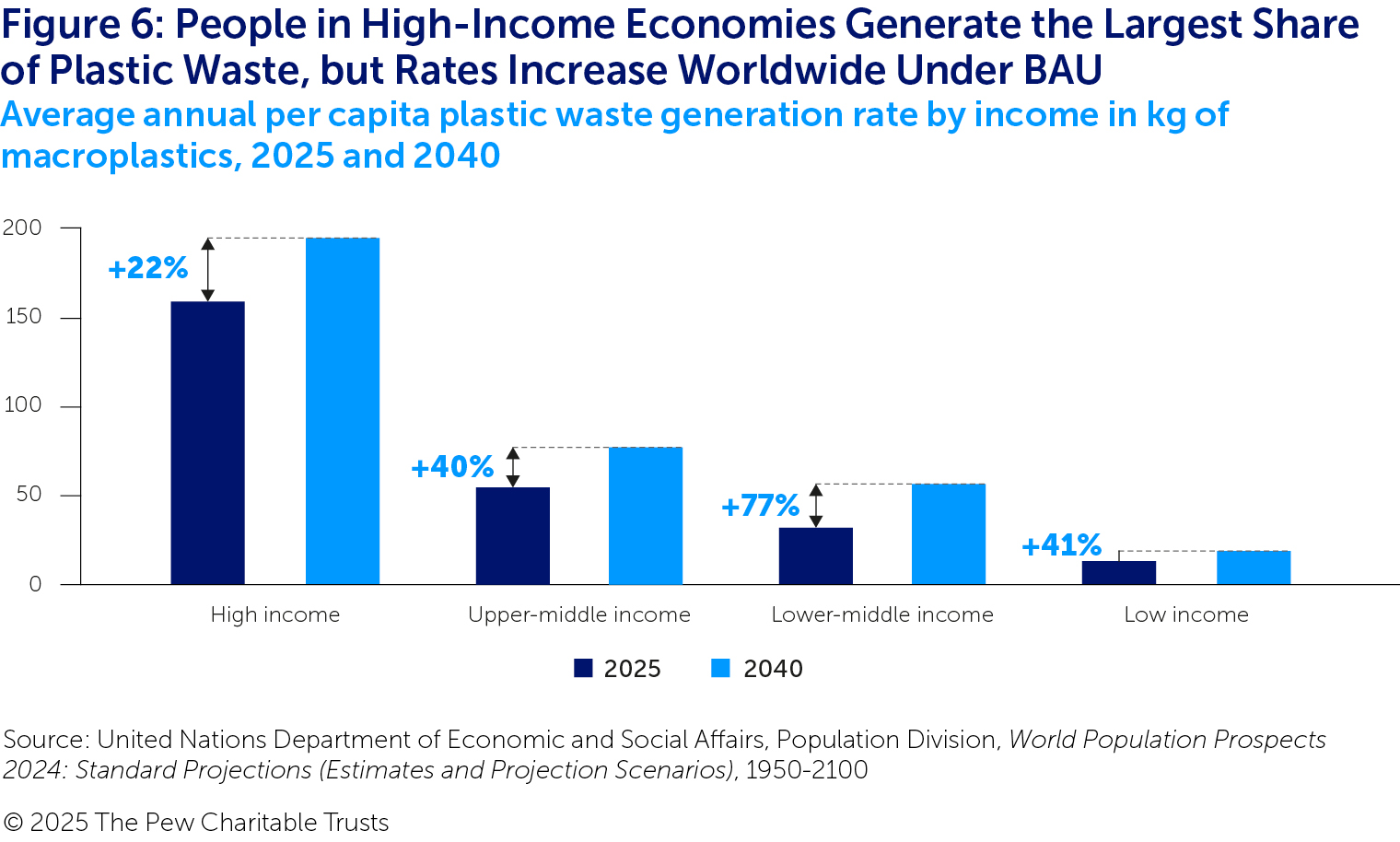

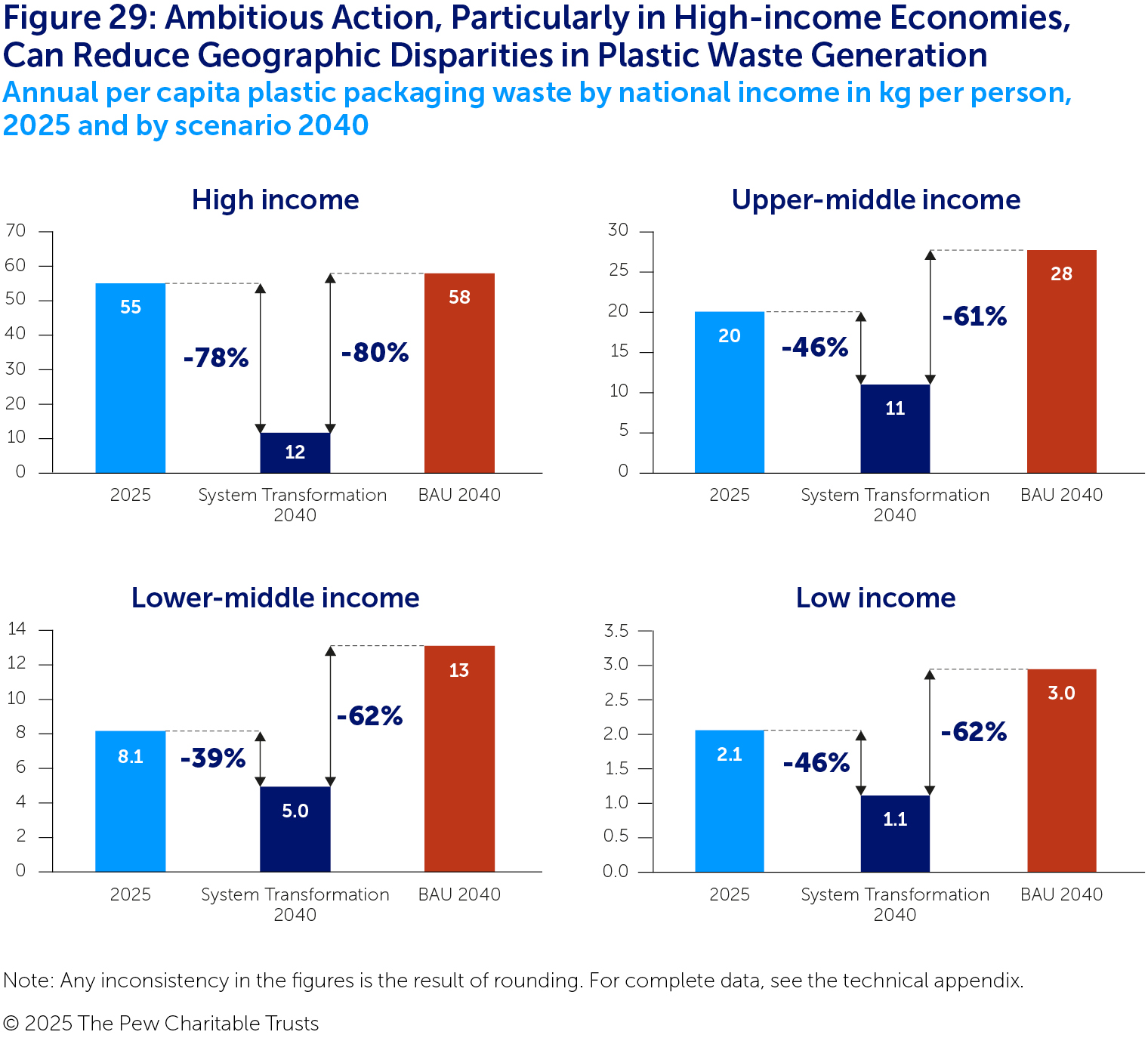

In 2025, annual per capita plastic waste generation in high-income economies is 160 kilograms (kg), 12 times the 13 kg of low-income economies. Under BAU, waste generation remains highest in the high-income economies, but substantial increases in the per capita plastic waste generation rate are seen in all economies, regardless of income level, over the 15-year period. (See Figure 6.)

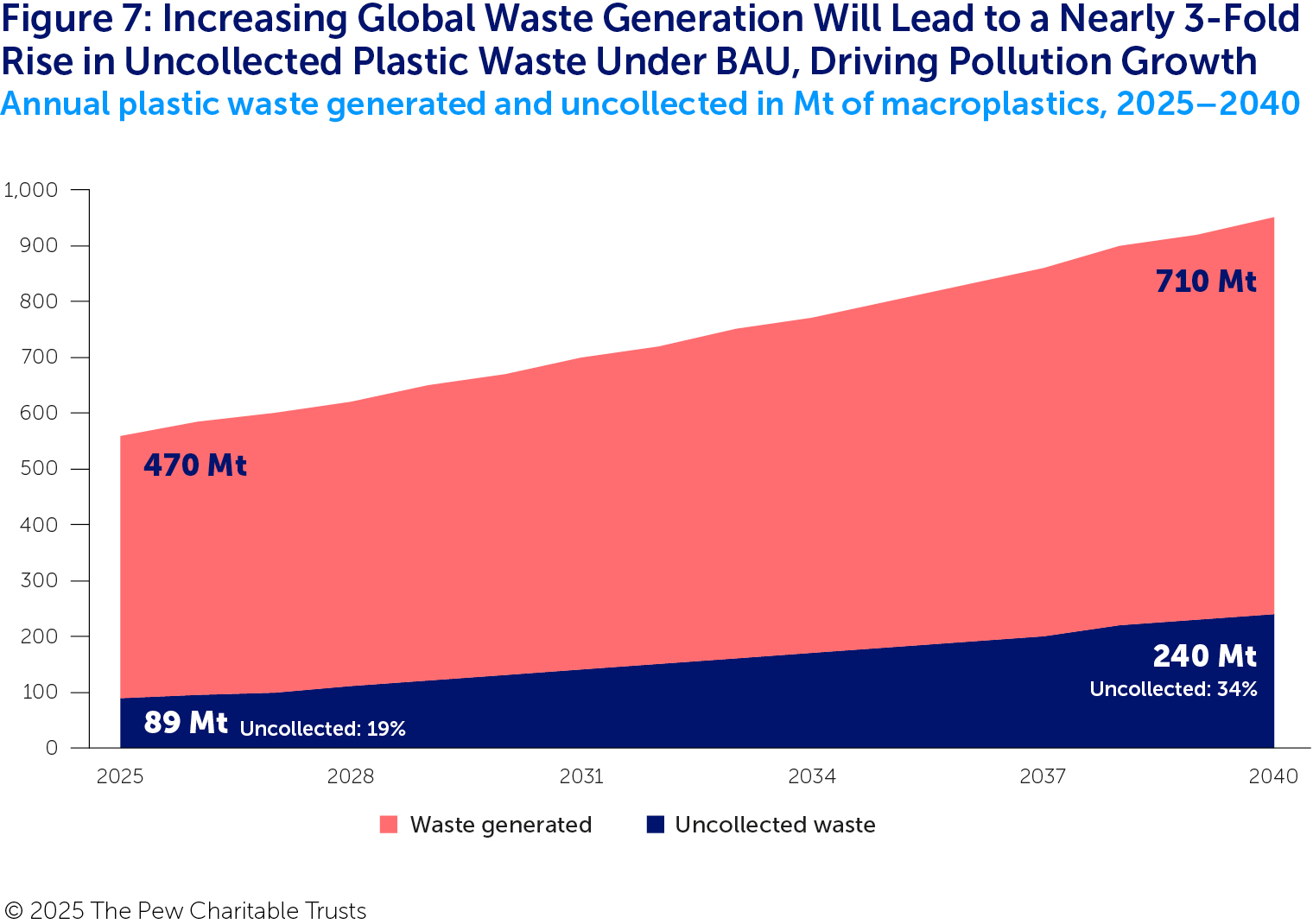

Waste management systems are already unable to keep pace with plastic waste. And in some parts of the world, waste management systems simply do not exist: An estimated 1.5 billion people live without access to waste collection services.53 Under BAU, waste infrastructure capacity will grow in line with global GDP, based on historical spending levels, reaching US$140 billion annually by 2040, but it still will not keep pace with rising plastic waste generation, widening the gap between the amounts of waste that are generated versus managed. In particular, the amount of plastic waste that is uncollected will increase sharply, nearly tripling from 2025 to 2040. (See Figure 7.) And this uncollected waste will flow into the environment as pollution or be disposed of via open burning, leading to additional air pollution.

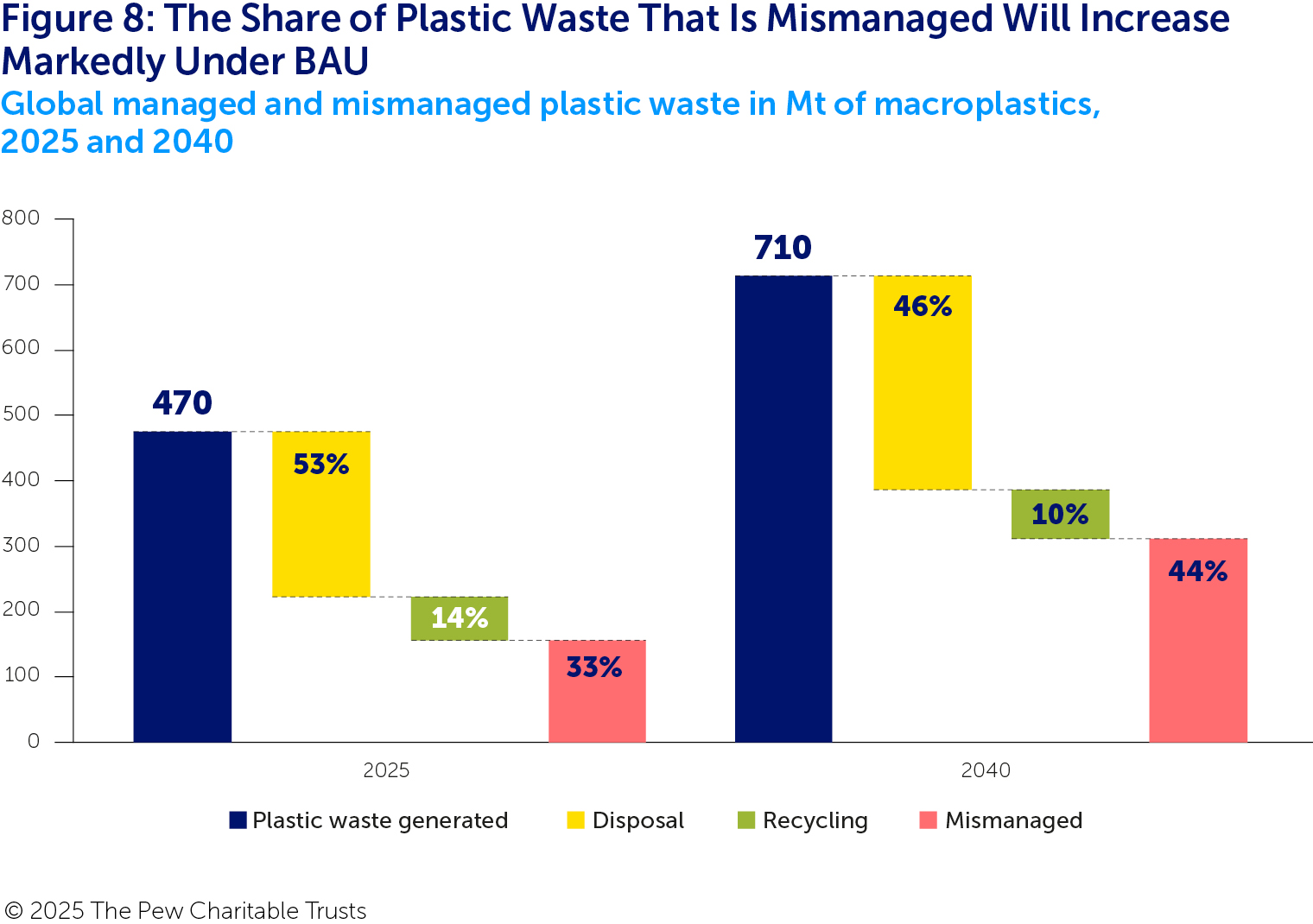

Within the waste management system, stagnating recycling rates – the share of collected plastic waste that is sent to recycling facilities – and constrained remaining landfill capacity compound the problem. (See Figure 8.) Although local governments and businesses continue to invest in new recycling infrastructure, plastic recycling – conversion of waste into raw materials for use in new products – still is only technically and economically viable for a small subset of polymers, such as polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and high-density polyethylene (HDPE).54 Furthermore, mechanical recycling reduces the strength, flexibility and other properties of plastic with each cycle, limiting the number of possible cycles and, in some cases, requiring that new primary material be added to the recycled material to maintain the desired quality.55 Recycling alone, therefore, can only slow, but not prevent, exponential growth of primary plastic production.56

Recycling Technologies

This report assesses three technologies for the recycling of plastic:

Closed-loop mechanical: Plastic is reprocessed into material (recyclate) that is used to make another product in the same category, such as when PET bottles are recycled to create new PET bottles.57

Open-loop mechanical: Plastic is reprocessed into recyclate that is then used in a different product application, including those that might otherwise not use plastic, such as benches or asphalt.58

Plastic-to-plastic chemical conversion: Plastic is chemically reprocessed into petrochemical feedstock that can be used to produce primary-like plastic. Some output from chemical conversion is refined into alternative fuels such as diesel, which we classify as plastic-to-fuel rather than recycling. Like mechanical recycling, chemical conversion can result in closed-loop or open-loop outcomes depending on the specific technology used.59

Annual plastic-related GHG emissions will increase by nearly 60% from 2025 to 2040

Under BAU, we estimate that the global plastic system’s annual GHG emissions will rise from 2.7 GtCO2e in 2025 to 4.2 GtCO2e in 2040, an increase of 58%. If the plastic system were a country, it would be the third-largest GHG emitter by 2040, behind only China and the United States.60

Our analysis includes GHG emissions from multiple stages of the plastic life cycle: primary production, formal waste collection and sorting, mechanical recycling and chemical conversion, controlled landfills, incineration, international trade in plastic waste and mismanagement of waste.61 Because of data limitations, we do not quantify emissions associated with several other key life-cycle stages, including plastic use and informal waste collection and sorting.

The production stage contributes by far the largest share (86% in 2025) of the plastic system’s emissions and, under BAU, those emissions will increase by 53% from 2025 to 2040. (See Figure 9.) Of the emissions occurring in later stages of the plastic system, open burning contributes the largest share (43% in 2025 and 59% in 2040), followed by incineration (33% in 2025, 23% in 2040). Emissions from open burning will increase by about 160% from 2025 to 2040 because of limited waste collection and mismanagement of increasing amounts of plastic waste.

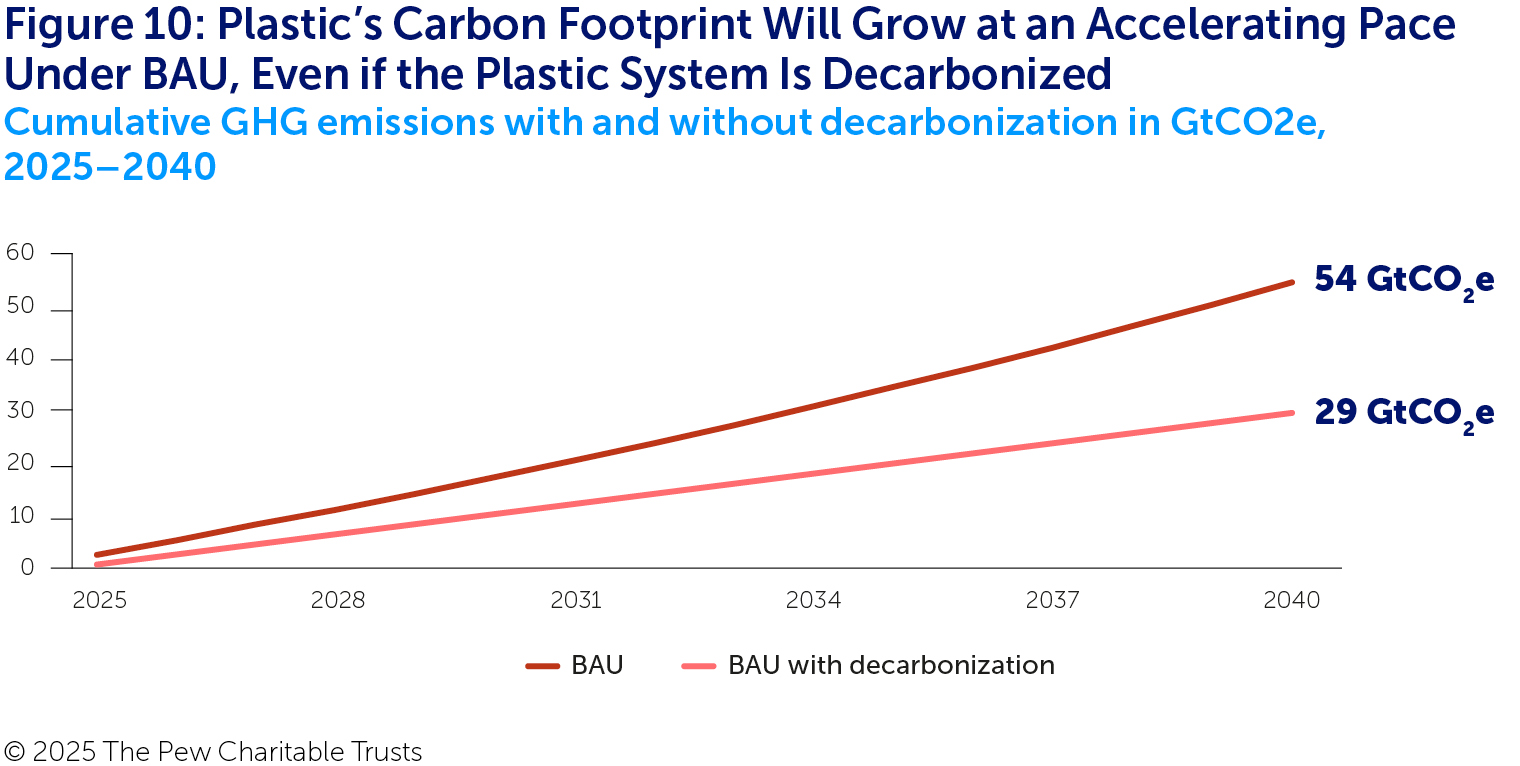

Global climate projections indicate that to have a 50% chance of limiting planetary warming to 1.5°C, the world has a remaining carbon budget of 130 GtCO2e, as of 2025, and to limit warming to 2°C, the remaining budget is 1,050 GtCO2e.62 We estimate cumulative emissions from the global plastic system from 2025 to 2040 to be 54 GtCO2e (see Figure 10), equal to 42% of the remaining budget to limit warming to 1.5°C and 5.2% of the remaining budget for 2°C.63 Even with ambitious decarbonization efforts across the global economy, cumulative emissions would be 29 GtCO2e, still more than one-fifth of the remaining carbon budget for 1.5°C, a clear signal that BAU is incompatible with the goals of the Paris Agreement.64

Health impacts from primary plastic production and post-consumer stages will increase by 75% by 2040

Our analysis explores human health effects at a high level to improve global understanding of the health implications of the plastic system, including from particulate matter formation, carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic toxicity, water consumption and climate change.65 We modelled global health impacts associated with macroplastic production, waste management and end-of-life for all sectors. Occupational hazards and the effects of using plastic products were beyond the scope of our analysis. Although we measured health effects using “disability-adjusted life years” (DALYs), with one DALY equivalent to the loss of one year of full health, we provide the results in years of healthy life lost, instead of DALYs, for ease of understanding.66 For more information on this modelling, see Appendix B.

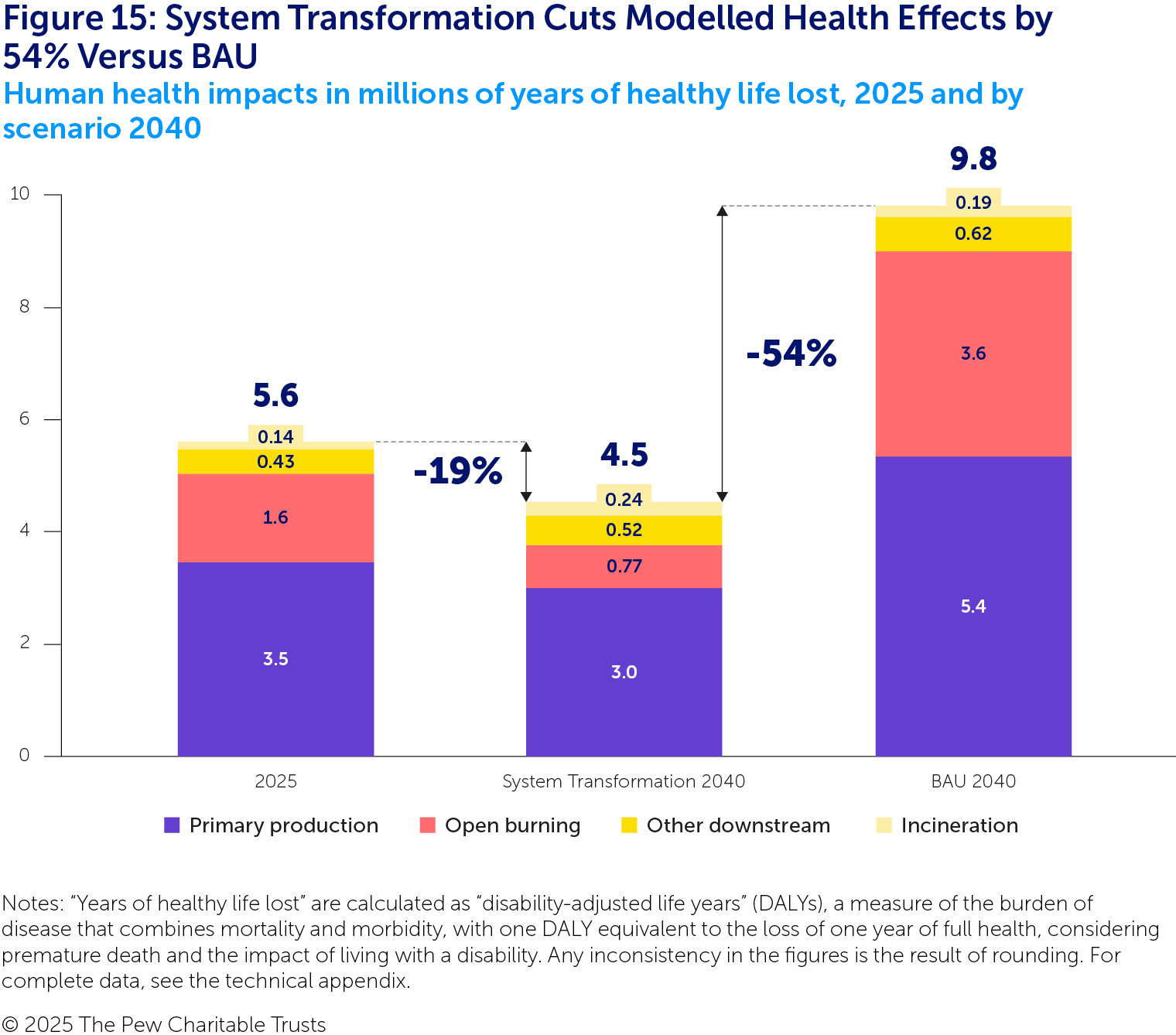

Under BAU, we estimate the modelled health impacts to be 5.6 million years of healthy life lost in 2025 and 9.8 million in 2040. (See Figure 11.)

Of all the life-cycle stages we modelled, primary polymer production accounts for most human health impacts (62% in 2025 and 55% in 2040), including cancers and respiratory diseases and climate-associated illnesses, such as heat stroke. Among all other stages of the plastic life cycle, open burning accounts for the largest share of health effects (73% in 2025 and 82% in 2040). Studies have shown that open burning’s health effects occur primarily through inhalation of particulate matter, which is associated with respiratory and cardiovascular disease and lung cancer and has important consequences for vulnerable communities and workers globally, but particularly in countries where open burning is most common.67

Because our analysis omits health impacts associated with the use of plastic products as well as other key life-cycle stages and exposures, it underestimates the reality of global health burdens, as well as the inequity of their distribution. Use-stage health effects could increase some impacts by an order of magnitude, particularly because of chemical exposures from plastic materials.68

Health impacts from exposure to fine particulate matter occur disproportionately across populations, often affecting the most disadvantaged communities.69 Our analysis found that most health effects in lower-middle- and low-income economies come from particulate matter inhalation and associated cardiopulmonary disease and lung cancer. Further, 75% of these estimated health effects are attributed to open burning, which is often used in the absence of adequate infrastructure or space for waste collection and management or for fuel.70 Under BAU, the health impacts of open burning will rise by nearly 130% from 2025 to 2040 to 3.6 million years of healthy life lost. As such, growth in open burning of plastic will have substantial implications for people’s long-term health, especially because the impacts could exceed those we modelled, such as through the accrual of toxic chemicals in soil and water sources.

Chemical exposures from plastic products could lead to additional health impacts

People are already exposed to thousands of chemicals through daily use of and contact with plastic.71 Certain groups of chemicals commonly found in plastic polymers and products are of major concern because of their known toxicity and high likelihood of human exposure through ingestion, inhalation or skin contact.72 To examine the relative hazard of chemical classes commonly used in plastic products and assess people’s likelihood of exposure, we estimated chemical exposures from toys and food packaging using data from USEtox, an internationally recognized model for the health impacts of chemicals.73

Although, because of gaps in the available data about chemicals used in plastic and plastic products, this analysis is only illustrative – a snapshot of potential hazards – it can still offer plastic producers, consumer goods companies and policymakers a glimpse of the potential risks and inform future decisions on chemical use and product design. For more detail on these methods, see the technical appendix.

Plastic toys

We modelled the health impacts on a 2-to-3-year-old child of playing with a plastic doll and other toys for one year to illustrate the potential range of health effects from toys. Studies have identified 71 chemicals, including plasticizers, fragrances and flame retardants, in soft polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastic toys.74 Of those chemicals, 15 have potential carcinogenic effects, and 62 have possible reproductive or developmental non-carcinogenic effects.75

The hypothetical doll for this model is composed of eight chemicals selected from the 71 identified chemicals: PVC polymer, a plasticizer, a stabilizer, a catalyst, a flame retardant, a pigment, a lubricant and a fragrance. Based on this model, we find that the health effects will vary substantially depending on the chemical additives used for each function, ranging from an estimated one hour to a few weeks of healthy life lost, and that, together, the flame retardant and plasticizer account for about three-quarters of the potential health impacts. These findings underscore the importance of design and formulation decisions in creating safer products.

Additional research is needed to better understand the chemical compositions of different types of toys and other daily-use plastic products and provide policy-relevant insights that could limit children’s chemical exposure. Such research could also help companies identify the most harmful chemicals, such as the flame retardant and plasticizer in our modelled toy, as well as safer alternatives to replace them.

Plastic food packaging

We modelled human exposure to 30 chemicals identified in PET bottles and found that the health effects were approximately one second of healthy life lost per bottle.76 However, this estimate is most likely conservative because it omits non-intentionally added substances that are probably also present but cannot be assessed as their properties are unknown.77

Although the effect of using a single PET bottle may be trivial, it illustrates the potential for harm from frequent bottle use, which for many people around the globe is often avoidable. Furthermore, most people interact with myriad products made of plastic every day, and the cumulative exposure and potential health consequences can add up.

Microplastics

By 2040, annual microplastic pollution from modelled sources will grow 50% under BAU

For this report, we modelled microplastic pollution from seven sources: tyre wear; washing of plastic at recycling facilities; mishandling of pellets during transport and at recycling and production facilities; washing of synthetic textiles; personal care products; application, wear and tear, and removal of paint; and agricultural products and practices.

Microplastic pollution from these sources will grow by 50% from 17 Mt in 2025 to 26 Mt by 2040, with cumulative pollution from the sources reaching 340 Mt. These seven sources account for roughly a tenth of global plastic pollution annually.

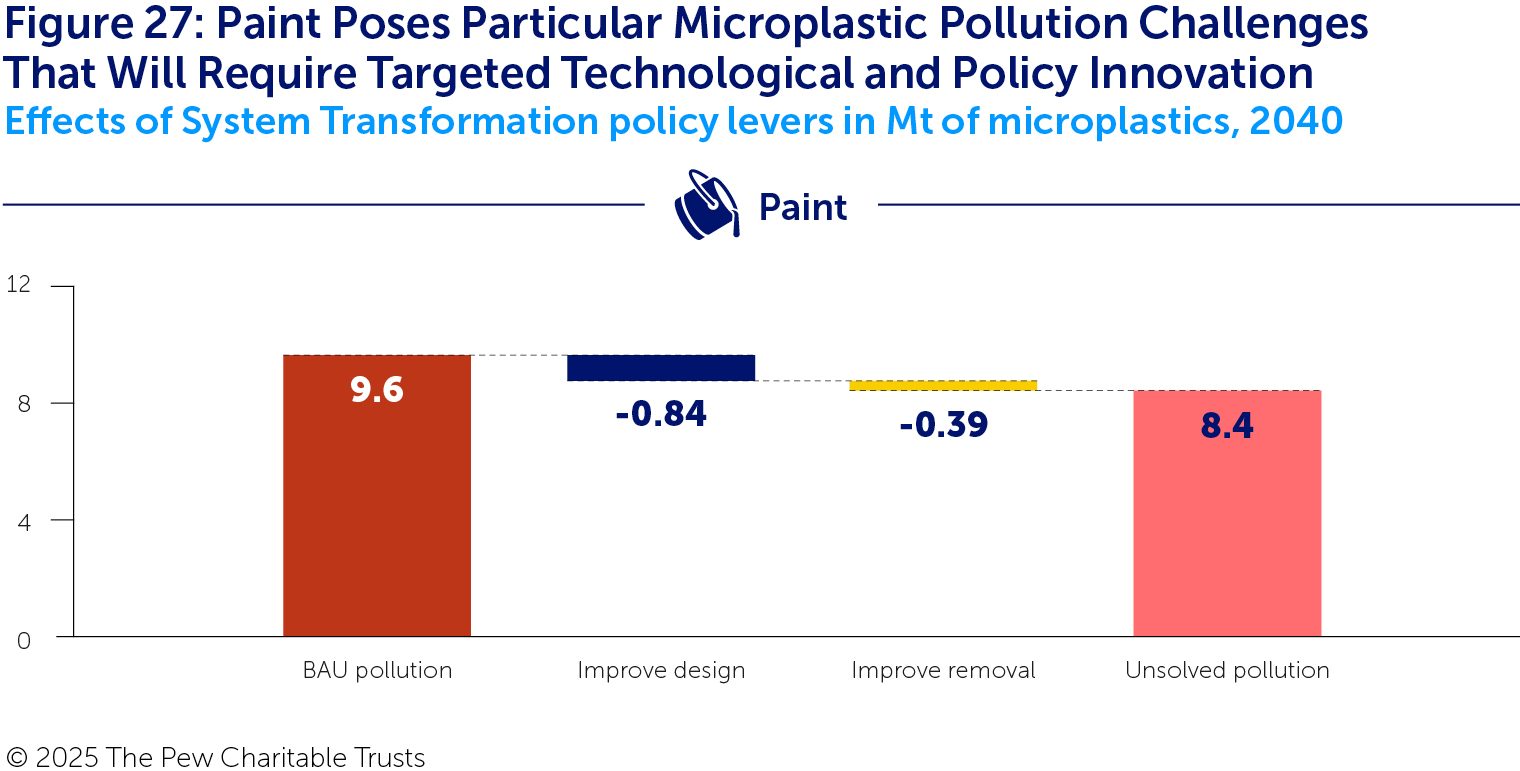

The largest sources of microplastic pollution are tyres and paint, followed by agriculture and recycling. (See Figure 12.) Tyres and paint both generate microplastics through everyday use and wear and tear over time. Although tyres with lower microplastic shedding rates are already on the market, decision maker attention on tyres as a major source of microplastics has only ramped up in recent years, and policies to reduce shedding have yet to be implemented.78 The countless uses of paint across economic sectors require tailored formulations to meet specific performance needs, resulting in a range of opportunities for microplastic releases – during application, weathering and removal – in diverse settings.79

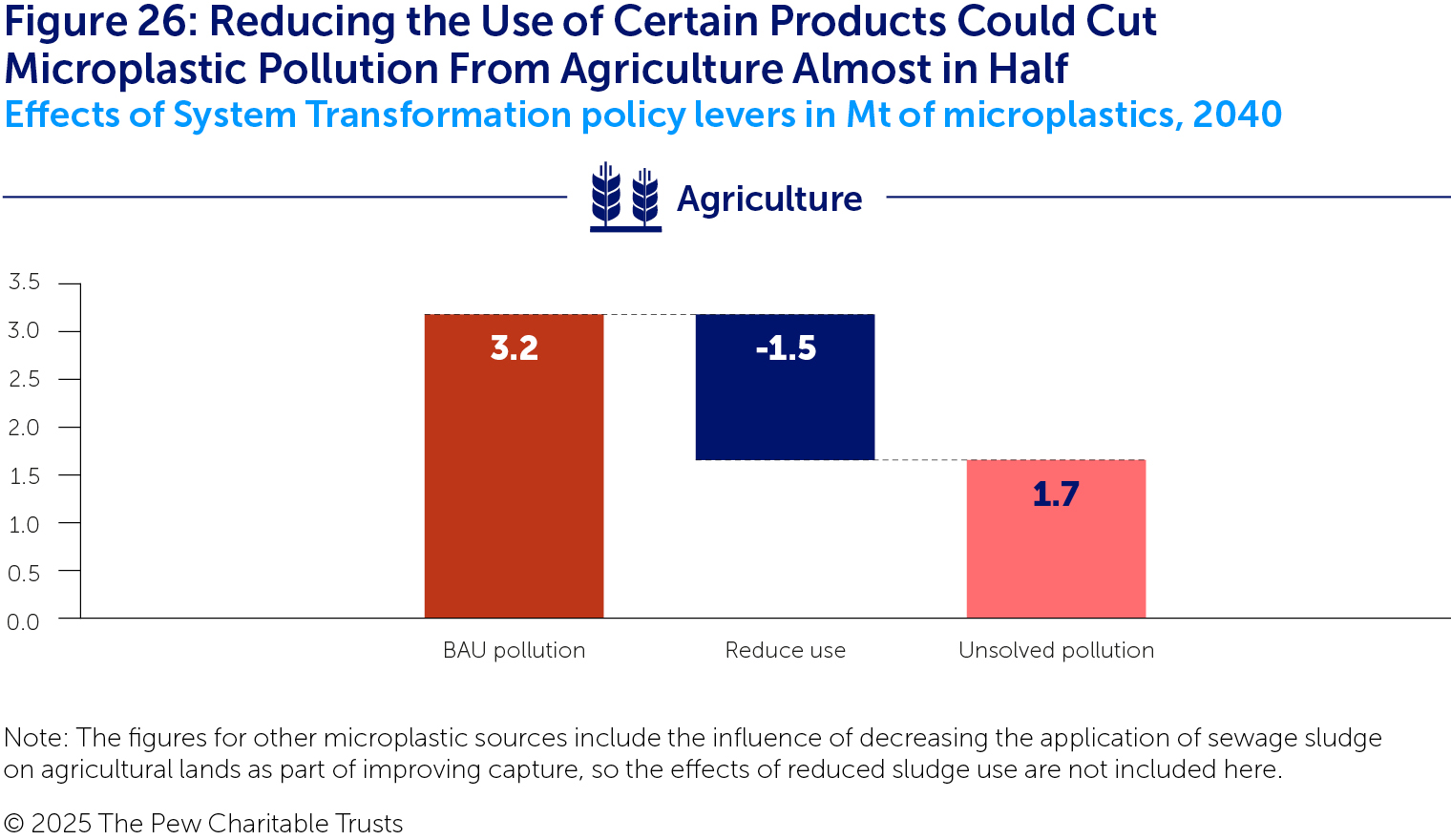

Agricultural plastic is the fastest growing source of microplastic pollution

This analysis provides some of the first estimates of global microplastic pollution from agricultural plastic and finds that, under BAU, microplastic pollution from short-term agricultural plastic, such as those used in seed and fertiliser coatings, plastic mulch and silage films, will grow from 1.9 Mt in 2025 to 3.2 Mt in 2040.

Agricultural microplastic pollution is also the fastest growing of the modelled sources, increasing by 66% over the next 15 years. Farmers use short-term agricultural plastic to increase crop yields and reduce pesticide use, but as that plastic degrades through weathering or is broken down by plowing and other practices, it generates microplastics that can harm soil quality, introduce contaminants and reduce plant growth and harvests.80 Products such as plastic mulch pose particular challenges because of their high soil contamination rates and the difficulty in removing them once applied.81

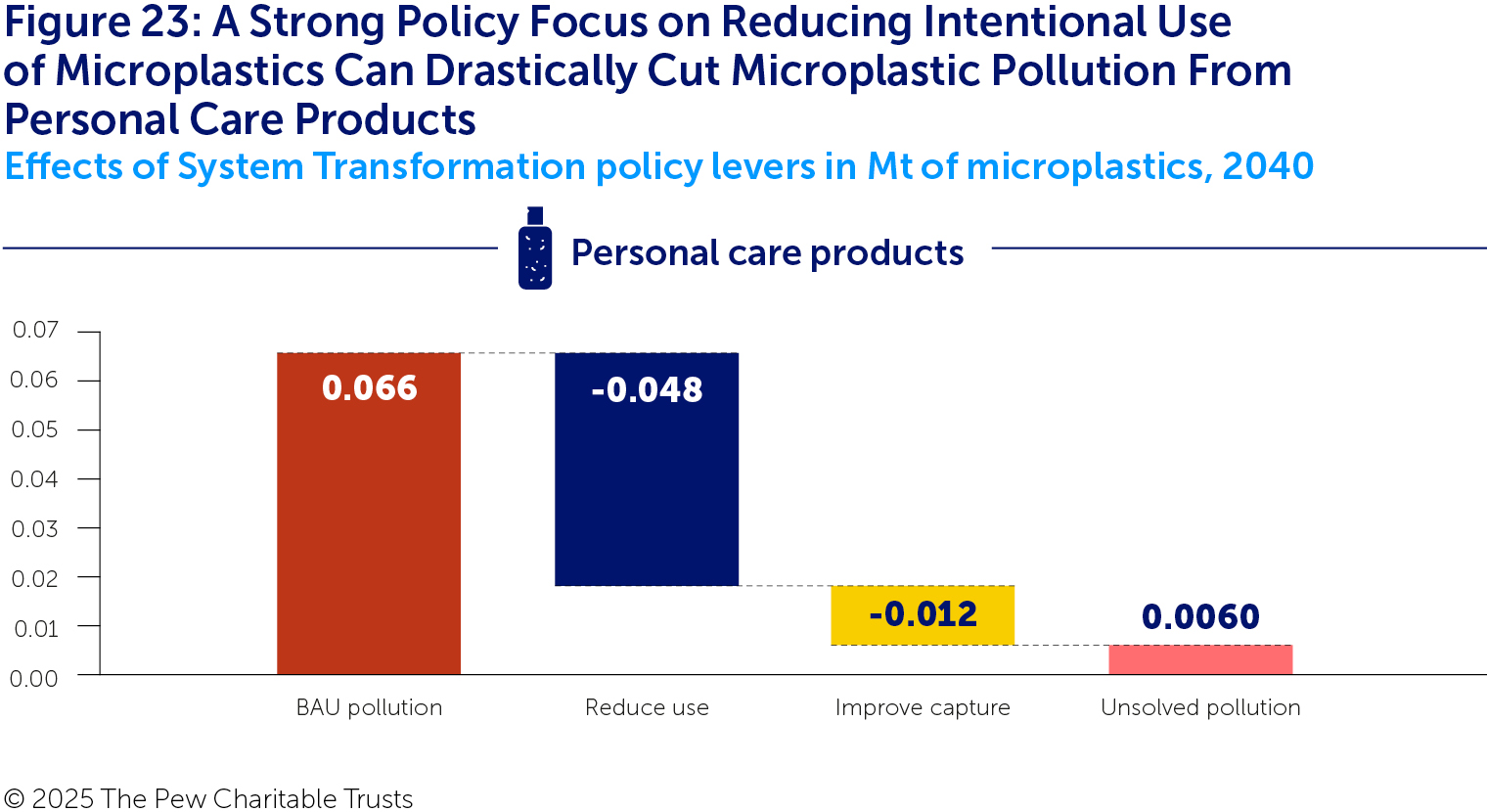

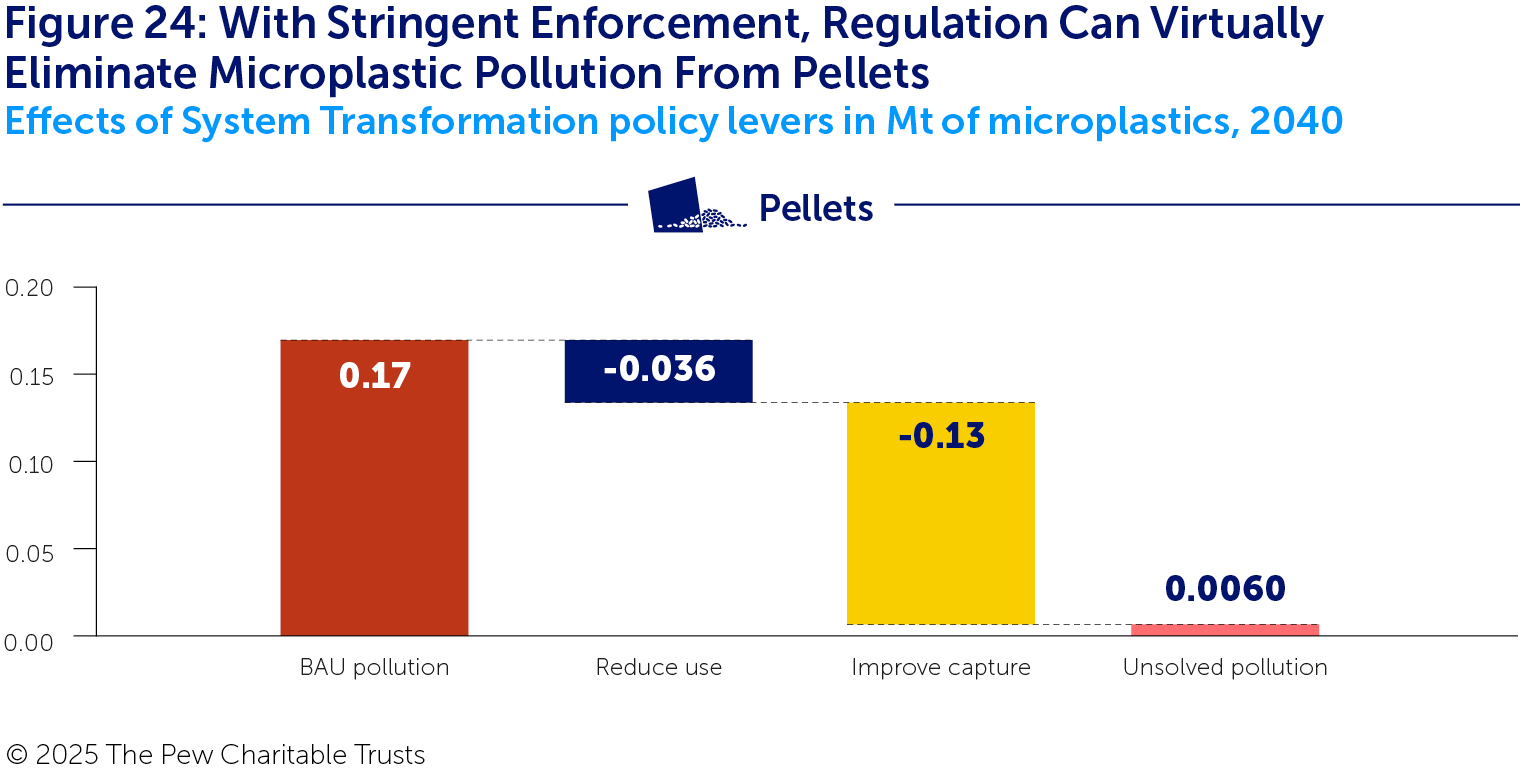

Smaller sources of microplastic pollution are still a significant concern

The remaining microplastic sources – pellets, textiles and personal care products – contribute far smaller amounts to the overall BAU microplastic pollution estimates, at a combined 0.2 Mt in 2025 and 0.3 Mt in 2040.

Microplastics added to personal care products are relatively straightforward to address and have received substantial attention in policy discourse, with many countries having already banned their use.82

Microplastic pollution from pellets occurs as a result of accidental spills and mismanagement. Although the volumes are much lower than those from tyres and paint, they remain substantial, with up to 7,300 truckloads of pellets lost into the environment each year in the EU alone.83

Further, microplastic pollution from the washing of textiles is likely to be higher than the modelled estimates when factoring in airborne emissions (which are not included in the scope of our analysis). One study estimated that up to 65% of textile microplastics may be emitted to aerial environments during the drying and wearing of garments.84 Although microplastics from textiles represent a relatively small portion of total microplastic pollution by mass, a single gram can contain 3.7 million individual fibres, and research has identified their elongated shape as particularly harmful.85

Plastic packaging

Pollution from plastic packaging will more than double from 2025 to 2040

Under BAU, packaging is the largest source of macroplastic waste among all sectors modelled, accounting for about one-third of all macroplastic waste generated. In this analysis, we disaggregate packaging flows by polymer and product type to evaluate how each affects the likelihood that plastic waste will be collected, be recycled or become pollution. PET and polypropylene (PP) are used in all of the six types of plastic packaging we modelled, and HDPE, low-density polyethylene/linear low-density polyethylene (LDPE/LLDPE), and PVC are each used in five types. (See Table 1.) Across packaging types, LDPE/LLDPE and PP are the most-used polymers, together accounting for more than half of the sector’s plastic use in 2025.

Table 1: The Most-Used Polymers in Plastic Packaging Are LDPE/LLDPE and PP, Followed by HDPE and PET

Composition of plastic packaging by polymer in Mt, 2025

| Product | Polymer | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDPE | LDPE/ LLDPE | PET | PP | PS/EPS | PVC | Other | ||

| PET bottles | 5.6 | 0.0 | 11 | 0.38 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 17 |

| Other bottles | 9.1 | 0.62 | 2.5 | 0.73 | 0.0 | 0.15 | 0.0 | 13 |

| Rigid food packaging | 3.6 | 0.62 | 4.5 | 15 | 2.3 | 0.33 | 0.092 | 27 |

| Rigid non-food packaging | 14 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 12 | 2.2 | 0.41 | 0.026 | 32 |

| Multilayer packaging | 0.0 | 6.1 | 0.32 | 0.38 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.048 | 8.1 |

| Flexible packaging | 3.9 | 35 | 1.1 | 15 | 0.69 | 1.5 | 0.40 | 58 |

| Total | 37 | 44 | 22 | 44 | 5.1 | 3.7 | 0.57 | 150 |

Notes: “PET bottles” include polymers other than PET in the caps and sleeves. “Other bottles” include some PET components, but the bottles themselves are made of other polymers. Any inconsistency in the figures is the result of rounding. For complete data, see the technical appendix.

The format of plastic packaging influences its fate within waste management systems; flexible and multilayer materials pose a particular challenge

Although under BAU most global packaging waste is collected (85% in 2025 and 70% in 2040), only a small portion of that collected waste is sent for recycling (21% in 2025, 19% in 2040); most goes to landfills (54% in 2025, 57% in 2040) or incinerators (12% in 2025, 13% in 2040).

Further, despite the prevalence of flexible and multilayer packaging, 96% of plastic packaging waste that is sent for recycling in formal systems is rigid because flexible and multilayer packaging present special challenges for waste collection, sorting and recycling. Flexible materials can get caught in recycling facilities’ sorting machinery, which is mostly intended for rigid plastic. Multilayer packaging typically consists of multiple sheets of plastic, made from various polymers and other materials, that are difficult to separate, and because it is often used in flexible formats, it also can pose the same issues as flexible packaging. Both packaging types are frequently used for food and personal care products, including as small packets or sachets to hold sample and travel-sized products and condiments, and can be soiled by the products inside. These characteristics of flexible and multilayer packaging make them more difficult and costly to recycle than rigid packaging, and the recyclate produced from flexible and multilayer materials is typically of low value and in limited demand.86

The informal waste management sector contributes about 60% of the plastic packaging waste sent for recycling

Nearly 12 million waste pickers in the informal sector are engaged in the collection and sorting of plastic waste in 2025, preventing substantial quantities of plastic from entering the environment. Of the 28 Mt of plastic packaging that recycling facilities receive globally in 2025, 61% (17 Mt) came via the informal sector, including virtually all plastic packaging sent for recycling in middle- and low-income economies.87 In contrast, high-income economies rely almost exclusively on formal waste collection and management systems.

System Transformation: A full-life-cycle approach to tackle plastic pollution

At the root of the plastic pollution problem are system-wide failures to match production and use of plastic to the design and capacity of the systems meant to manage the resulting waste. Current levels of production and consumption – particularly for single-use or short-lived packaging, textiles and consumer goods – overwhelm the waste management system and generate cascading impacts on human health and the environment. To be effective, solutions must therefore be system-wide.

The System Transformation scenario explores the potential of deploying existing policy strategies and tools to tackle plastic pollution through upstream (i.e. the pre-consumer phase of a product or material life cycle) measures that reduce plastic production and downstream (i.e. the post-consumer phase) measures that increase collection, sorting and recycling. And it draws on the discussions surrounding the U.N. plastics treaty negotiations to highlight the benefits of international cooperation to rapidly bring solutions to scale worldwide. All figures in this chapter are projections based upon our modelling unless otherwise cited.

Our analysis included two versions of System Transformation – high impact and low impact – which differ in the time and impact assumptions used for each policy lever. To emphasize the vast potential of substantial global collaboration and commitment, this chapter presents the results of high-impact System Transformation.88

System Transformation cuts plastic pollution by more than three quarters

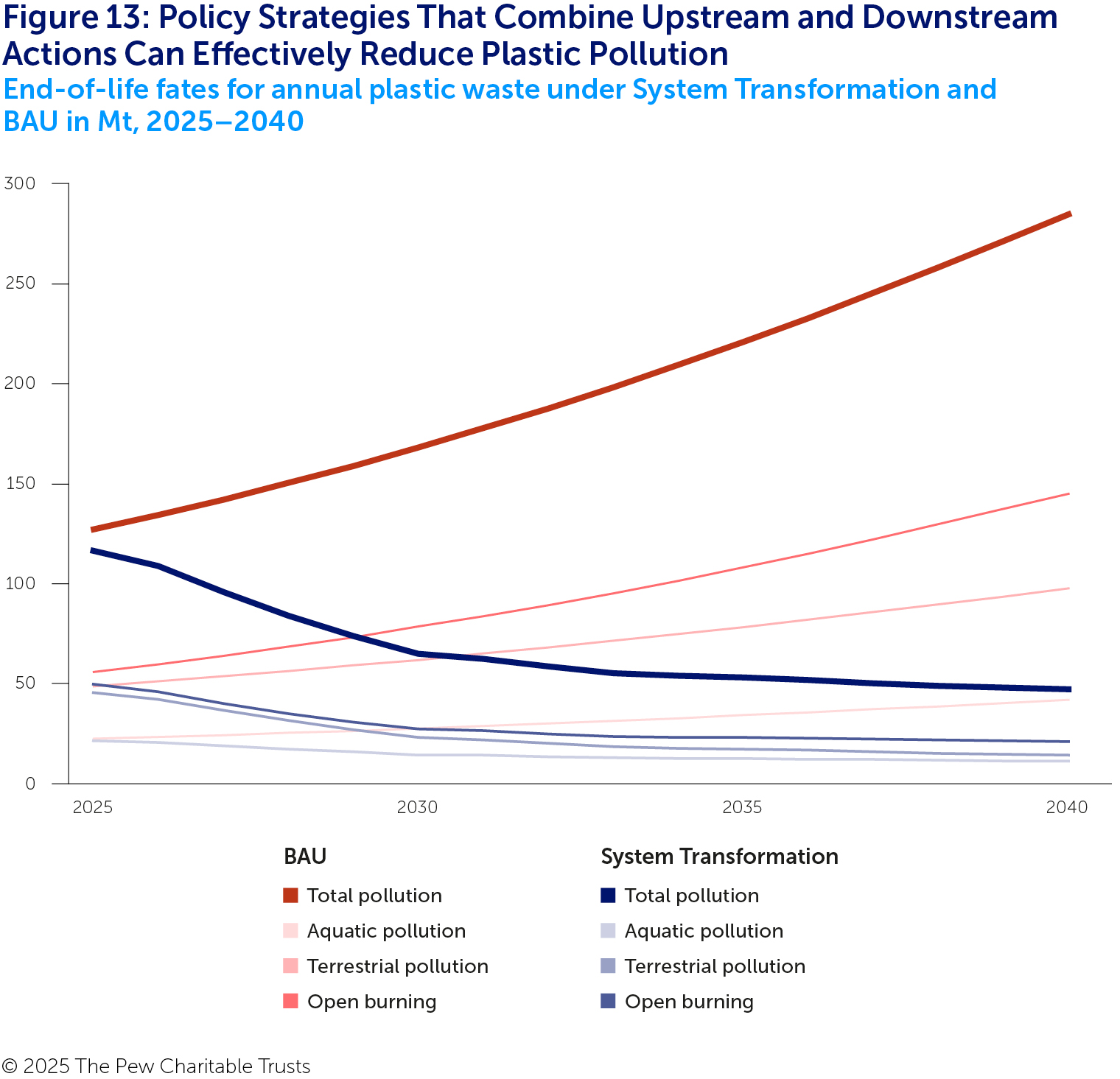

Under System Transformation, by 2040, annual combined macroplastic and microplastic pollution falls by 83%, from 280 Mt per year under BAU to 47 Mt per year. (See Figure 13.) The mass of macroplastic that is disposed of via open burning decreases by 85% by 2040 relative to BAU, substantially reducing health impacts of air pollution from the burning of plastic waste.

The reductions in environmental pollution achieved under System Transformation stem from an overall decrease in plastic production coupled with improved waste management. By 2040, annual primary macroplastic production decreases to 390 Mt, a 44% cut versus BAU (680 Mt) and 14% from 2025 (450 Mt).

Although substantial, these results fall well short of recent calls – such as those made by the Rwandan and Peruvian delegations during the fourth session of the U.N. plastics treaty negotiations – to achieve a 40% reduction by 2040 from 2025 levels and of the more drastic cuts that studies indicate are necessary to align with the Paris Agreement.89 To reach those targets, the global community will need to identify additional opportunities to reduce primary production in the non-packaging sectors. These could include eliminating subsidies for plastic production, taking strategic pauses on building new infrastructure in places where excess production capacity exists, and providing policy and financial support to encourage new reuse business models. We provide more discussion of relevant strategies to address production and use in the chapter titled, “4 strategic pillars can drive plastic system transformation.”

System Transformation requires improvements in material circularity

System Transformation also involves significantly improved waste management, as well as higher rates of reuse – which is explored in detail for packaging later – and recycling. By 2040, compared with BAU, the collection rate for macroplastics grows from 66% to 97% and the recycling rate increases from 17% to 34%. In particular, the share of plastic waste that is recycled via closed-loop mechanical recycling rises substantially, resulting in a nearly three-fold increase in the amount of recycled plastic material used to make plastic products compared with BAU. Although the amount of plastic waste reprocessed via chemical conversion increases more than 20-fold based on industry-projected growth rates, it still totals only 0.056 Mt in 2040, suggesting that capacity and cost barriers – such as those related to sourcing quality materials that prevent many existing facilities from operating at full capacity – may be difficult to overcome.90 For more information, see the later section of this report on chemical conversion.

The growth in use of recycled plastic in new products reflects a shift away from open-loop mechanical recycling and incineration, which both begin to decline around 2035 in System Transformation. Whether this shift can be achieved will depend on the policy priorities of local, regional and national governments and on whether the private sector makes meaningful product design changes over the next few years. Unlike landfills, incinerators require continuous feedstock to be cost effective, and because their lifetime is 25 years or longer, incinerators can block newer technologies and compete for material that could otherwise be recycled.91 For example, Sweden does not generate enough waste domestically to supply its incinerators and relies on imported waste, putting incineration in competition with efforts to improve sorting and recycling of plastic, not only in Sweden, but also in neighboring countries.92

Therefore, investments in open-loop mechanical recycling and incineration made now risk becoming barriers to alternative technologies that could play a longer-term role in reducing plastic pollution. We estimate that over the 15-year time frame of System Transformation, capital expenditures for open-loop mechanical recycling and incineration will total US$430 billion (discounted at 3.5%) – investments in technologies that risk becoming obsolete as the world transitions to a more streamlined circular plastic economy.

System Transformation benefits the climate and human health

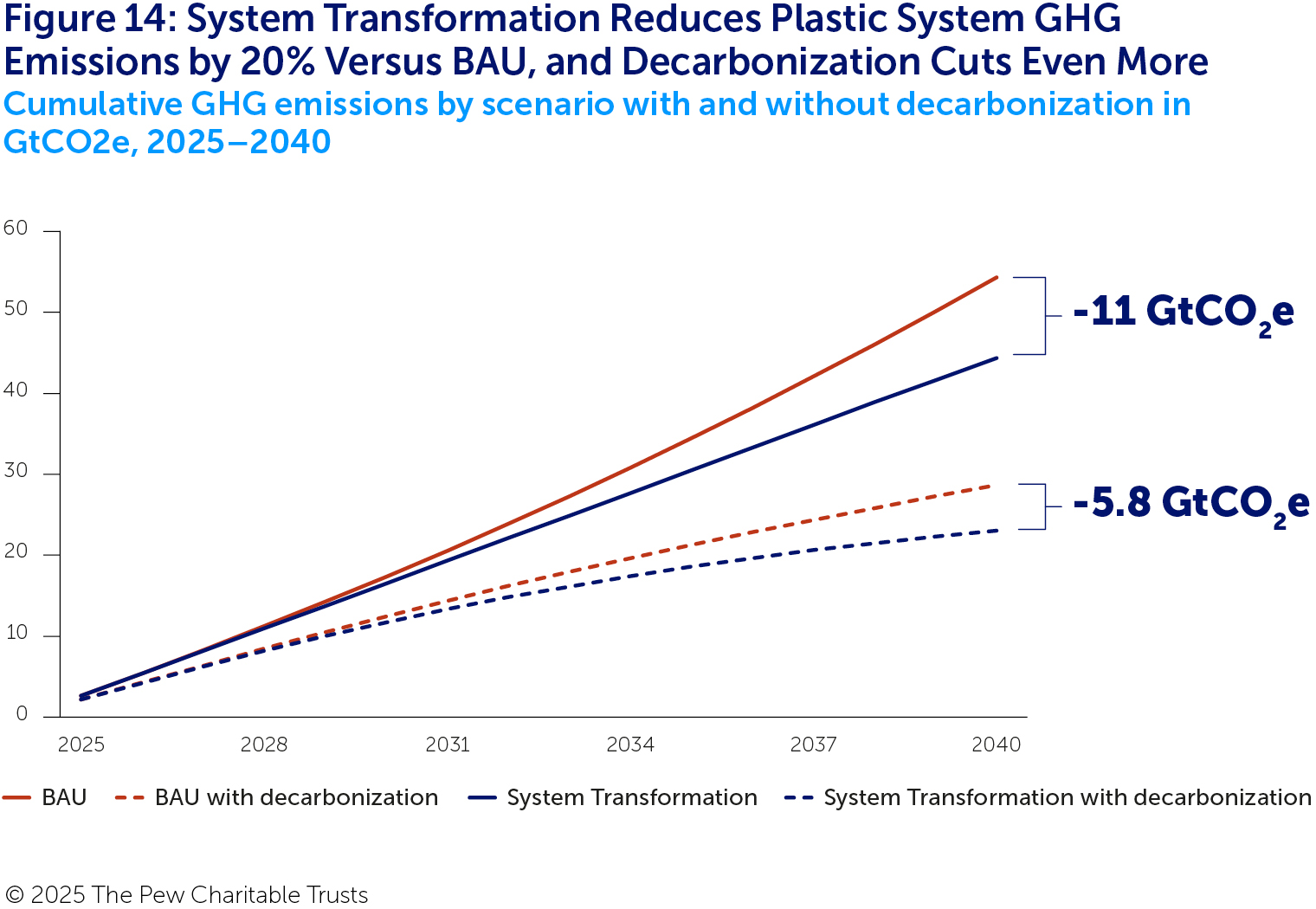

The dramatic changes that occur under System Transformation have important implications for the climate and human health. By 2040, System Transformation achieves a 38% reduction in annual GHG emissions relative to BAU, mostly from decreased primary plastic production. Cumulative emissions fall to 44 GtCO2e, accounting for 33% of the remaining overall carbon budget for a 1.5°C climate target or 4% of the budget for a 2°C target. (See Figure 14.)

When global decarbonization efforts are included, cumulative GHG emissions under System Transformation total 23 GtCO2e by 2040, with annual emissions declining to less than 1 GtCO2e per year. And further reductions in plastic production and use could deliver long-term net-zero GHG emissions for the plastic system. However, the plastic sector’s heavy reliance on fossil fuels for primary plastic feedstock presents a significant barrier to decarbonizing the plastic system enough to realize net-zero GHG emissions.93

The results of System Transformation highlight the importance of addressing the full plastic life cycle, including use of alternative materials and new business models, to reduce climate impacts. Annual GHG emissions from production decline by 38% from 3.5 GtCO2e to 2.2 GtCO2e per year by 2040, while emissions from open burning fall 86% from 0.42 to 0.06 GtCO2e. Modelled human health impacts – which do not include effects from the use stage or chemical exposures – also decrease substantially. By 2040, System Transformation is associated with an estimated 4.5 million years of healthy life lost, which is 54% below the BAU figure of 9.8 million years, largely as a result of the projected decreases in primary production and open burning. (See Figure 15.)

Reductions in health impacts from open burning are most noticeable in upper-middle- and lower-middle-income economies – the largest contributors to open burning under BAU – where a decrease of 119 Mt annually in the amount of open burned plastic waste yields an 86% drop in health effects. Achieving such a big decline in open burning would take a concerted global effort, but it would yield substantial health benefits.

System Transformation will require shifts in investments and jobs across the plastic system

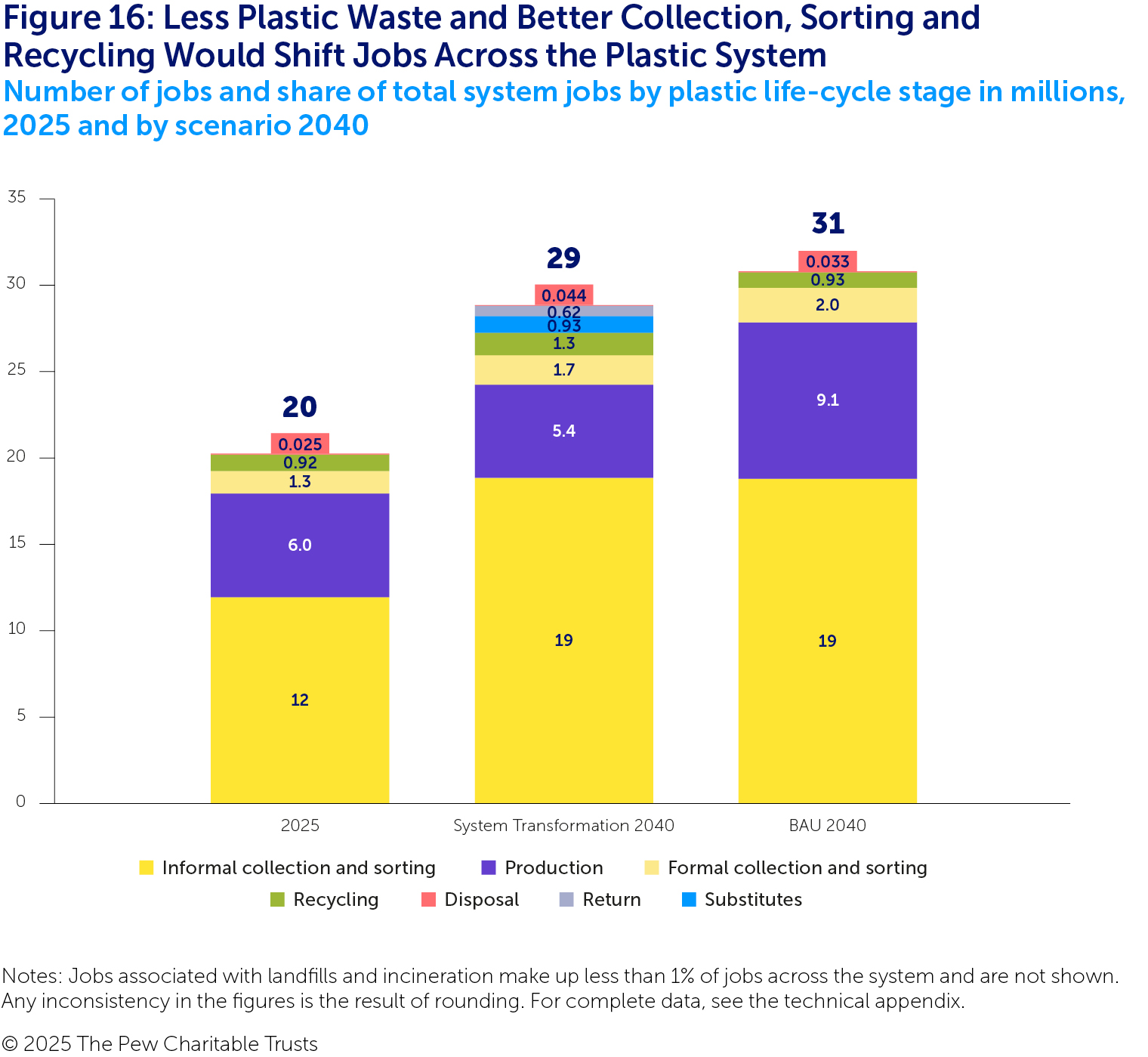

Under System Transformation, annual plastic system costs are US$2.3 trillion in 2040. Although that figure is just 4% (US$89 billion) less than BAU, the distribution of spending and jobs across the system changes substantially between the two scenarios. Annual spending on primary plastic production under System Transformation decreases – because of lower production – by 40% (US$790 billion) compared with BAU. And less production means less waste generation, which leads to public spending decreases for plastic collection, sorting and disposal of US$19 billion, a 13% reduction relative to BAU. However, because more plastic will be recirculated in the economy, spending on recycling is 39% higher – US$76 billion more a year – under System Transformation than under BAU.

Despite this shift in spending, the total number of plastic waste management jobs is virtually the same under System Transformation and BAU. (See Figure 16.) However, improved waste management under System Transformation results in a shifting of jobs across the system by 2040 versus BAU, with formal waste collection jobs decreasing by 340,000 (18%), formal sorting jobs growing by 68,000 (75%) and recycling facility jobs increasing by 360,000 (39%).

Overall, System Transformation results in 40% fewer plastic production jobs and 6% fewer total jobs compared with BAU in 2040. However, some of the losses are offset by increased jobs associated with substitute materials (930,000) and reuse systems (620,000). Moreover, we only modelled substitution and reuse, and their associated employment impacts, for the packaging sector, but use of these levers in other sectors would probably further compensate for production job losses. Ultimately, System Transformation still reflects 8.6 million more jobs than in 2025.

The largest concentration of plastic waste-related jobs is in the informal sector, which we estimate at about 19 million jobs under both BAU and System Transformation in 2040, reflecting waste pickers’ critical role in meaningfully reducing global plastic pollution and in the economic opportunities and development of their local communities. This is particularly true in lower-middle-income and low-income economies, where informal sector jobs will increase by more than 1.6 million (16%) in 2040 under System Transformation.

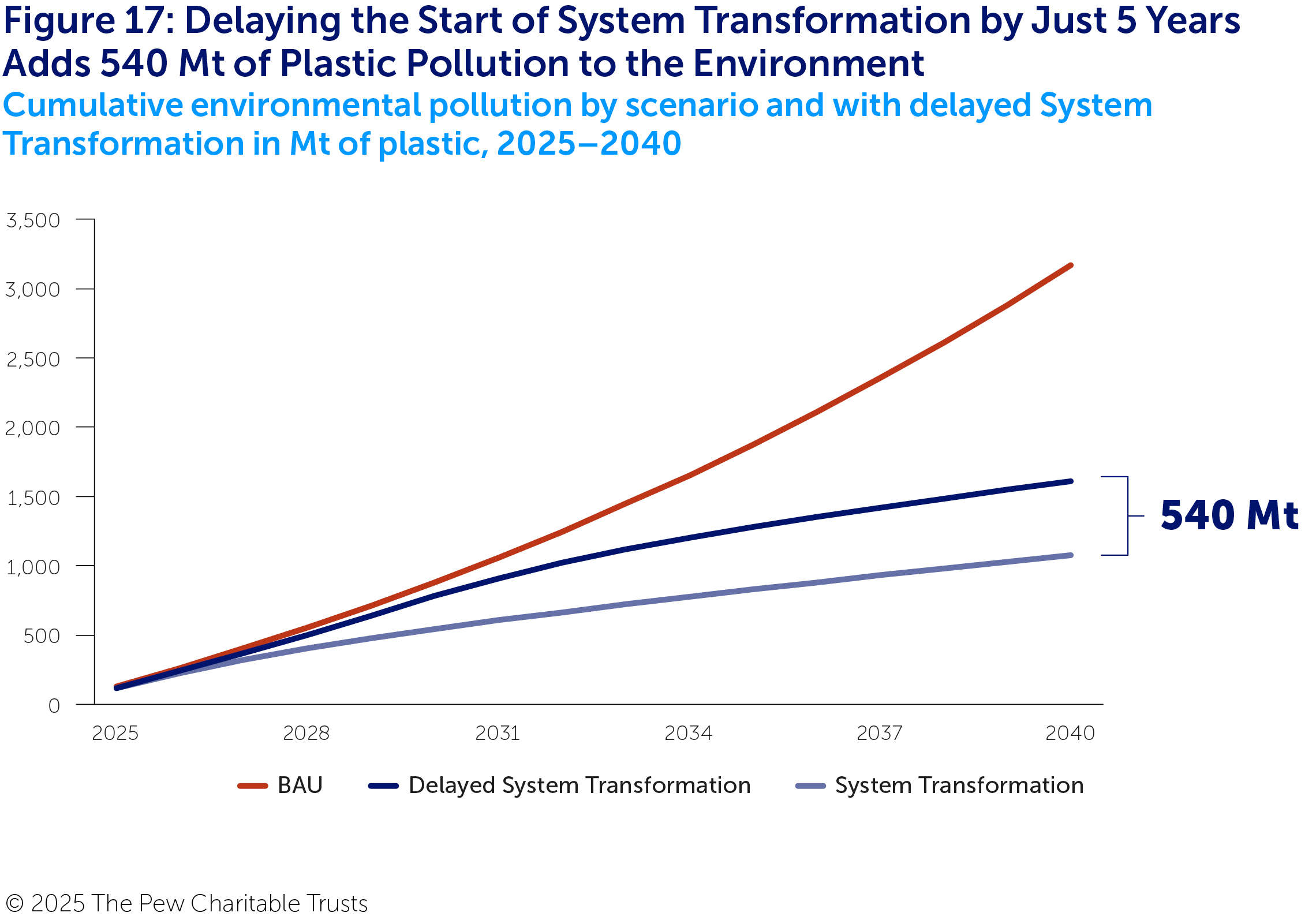

The costly consequences of delay

The results presented in this chapter assume that action to implement system-wide changes begins in 2025 and takes 15 years. A five-year delay in starting that effort would increase cumulative environmental pollution by 540 Mt by 2040 versus System Transformation as modelled. (See Figure 17.)

Compared with starting System Transformation in 2025, a five-year delay would:

- Increase annual public costs by 23%, or US$27 billion by 2040, to curb 1,100 Mt more primary plastic that would be produced cumulatively over the next 15 years.

- Add 5.3 GtCO2e in cumulative plastic system GHG emissions by 2040.

- Increase the risk of overinvestment in activities focused on disposing of the additional plastic waste. For example, some countries are struggling to manage public spending decisions, such as between new but underutilized incineration plants and efforts to improve sorting and recycling that would further divert materials from those plants.94

Urgent action is required not only to curb the worst effects of plastic pollution and the broader effects of the plastic system on the environment and human health, but also to ensure the efficient use of limited global funding.

Microplastics

Policy measures to reduce microplastic pollution have evolved substantially over the past decade. The Netherlands led the way in 2014 when it introduced the first ban on microbeads in personal care products, which was followed by similar rules in several other countries.95 The following year, the U.S. enacted the Microbead-Free Waters Act of 2015 that prohibits the use of microbeads in rinse-off cosmetics and over-the-counter health care products, such as toothpaste.96 In 2023, the EU restricted the intentional addition of microplastics in cosmetics, personal care, detergents and other products and is in the process of enacting regulations on tyres, pellets and textiles.97 Multinational organizations such as the International Maritime Organization and the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization are also beginning to act, and measures to target microplastics have been included in drafts of the U.N. plastics treaty.98

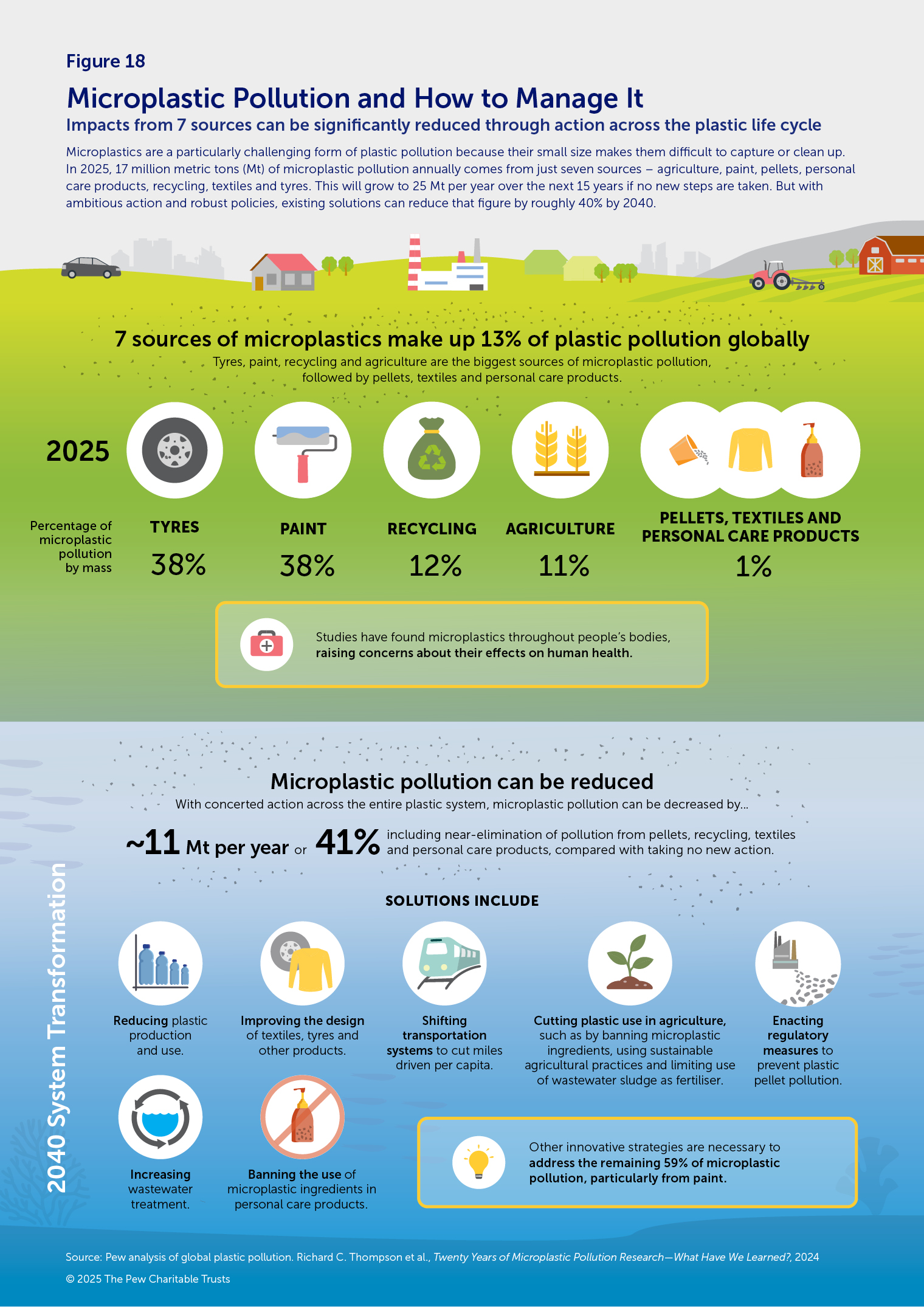

System Transformation includes upstream and downstream policy actions tailored to each of the seven modelled sources of microplastic pollution. (See Figure 18.) The upstream actions broadly involve reducing the intentional use of microplastics in products and improving product design to reduce the amount of microplastics they shed. Downstream actions include installing water filters in industrial and household settings and reducing agricultural use of sewage sludge. For a detailed list of the recommended policies, see Appendix C. For more information on data and methods, see the technical appendix.

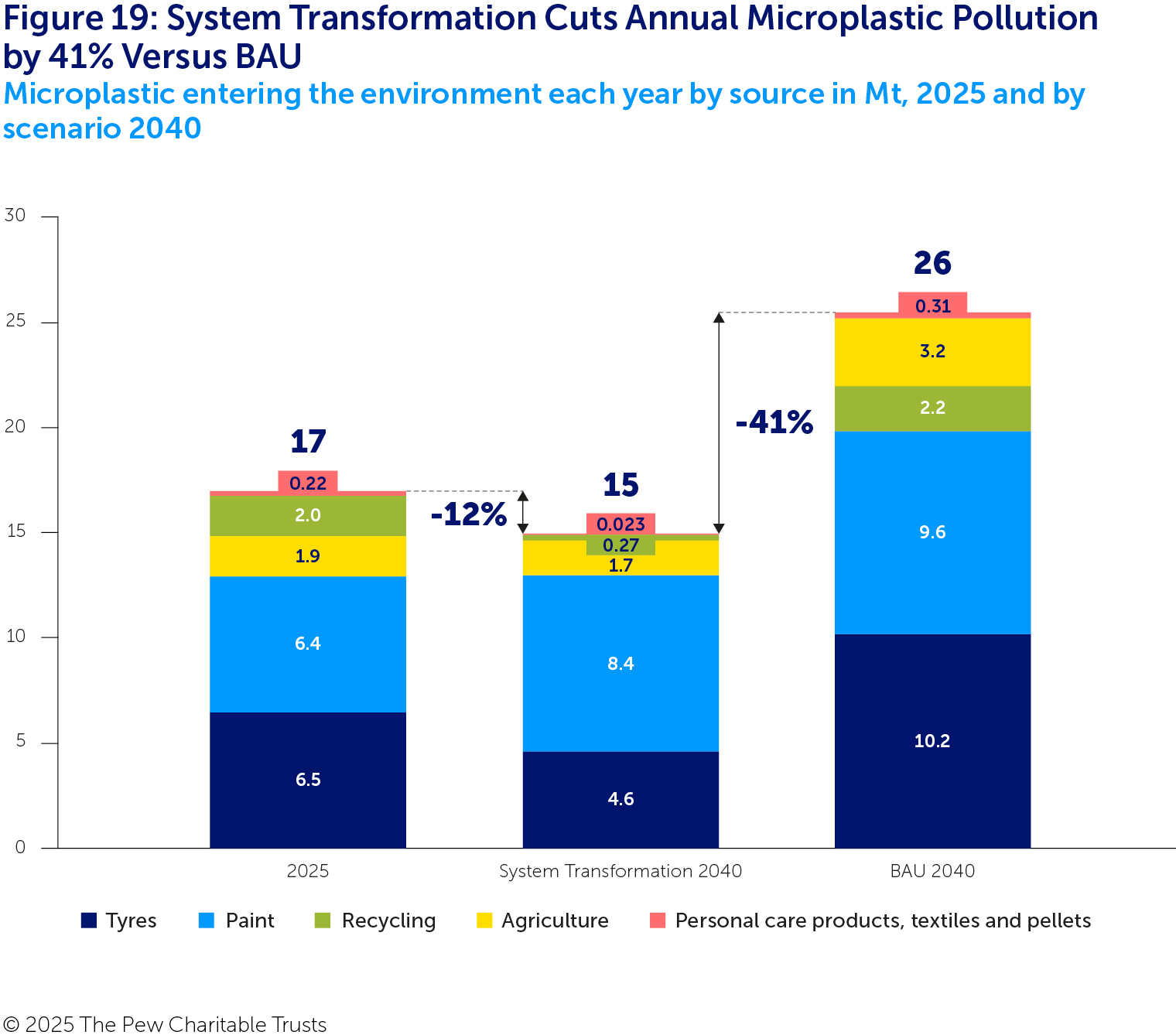

System Transformation cuts microplastic pollution by 41% by 2040 relative to BAU

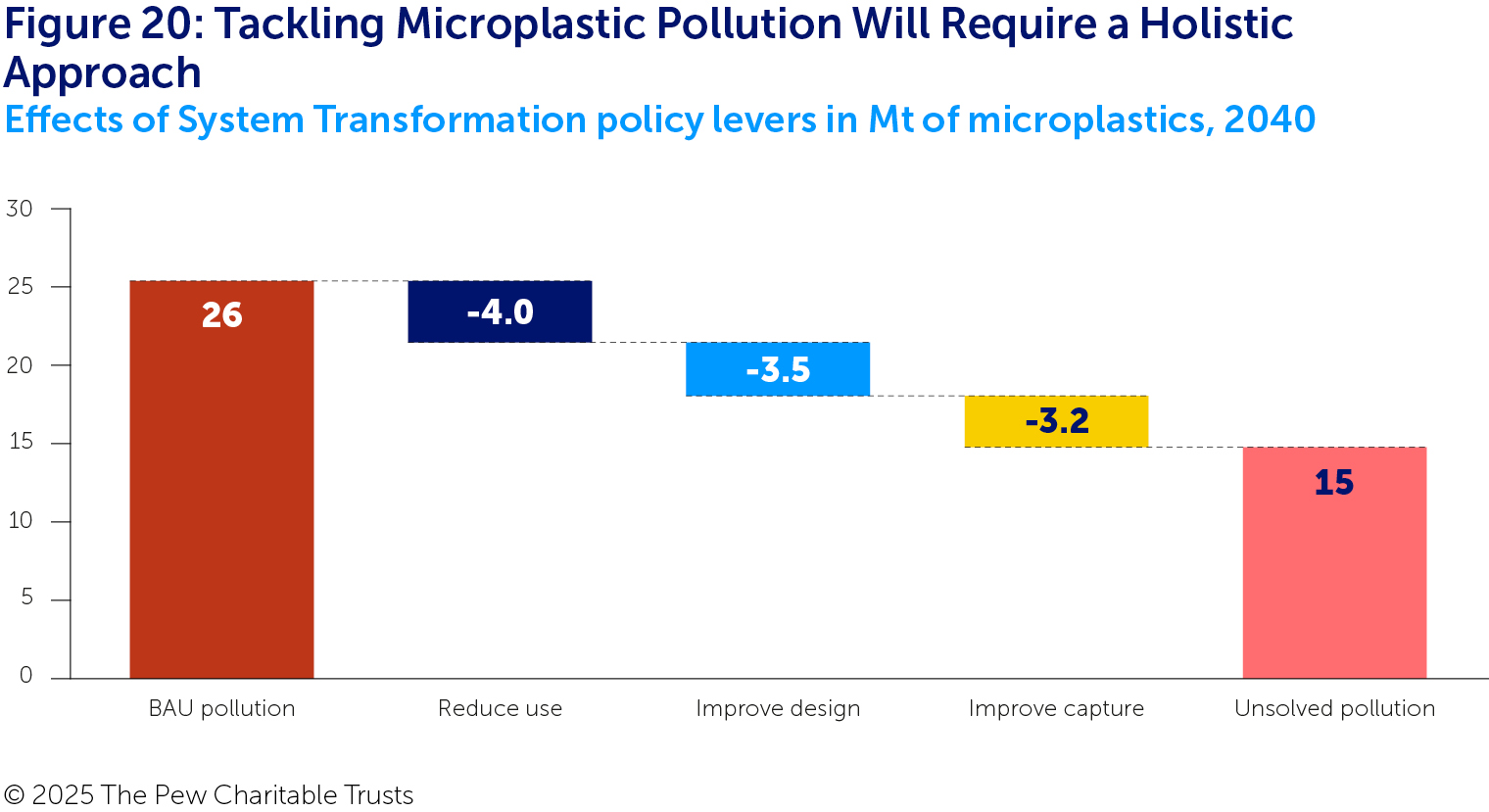

By 2040, System Transformation reduces microplastic pollution entering the environment from the modelled sources by 41%, from 26 Mt under BAU to 15 Mt. (See Figure 19.) Although this result shows that targeted action can substantially cut microplastic pollution, it also is only about half of System Transformation’s effects on macroplastic pollution, highlighting the need for additional dedicated policies for microplastics, especially in high-income economies, where microplastic pollution makes up 92% of total plastic pollution under System Transformation in 2040.

Microplastic pollution is generated at multiple stages across product life cycles and requires a multipronged solution. (See Figure 20.) Reducing overall use of microplastics and improving product design can decrease microplastic shedding. And providing more and better water filtration and wastewater treatment can increase the capture of emitted microplastics.

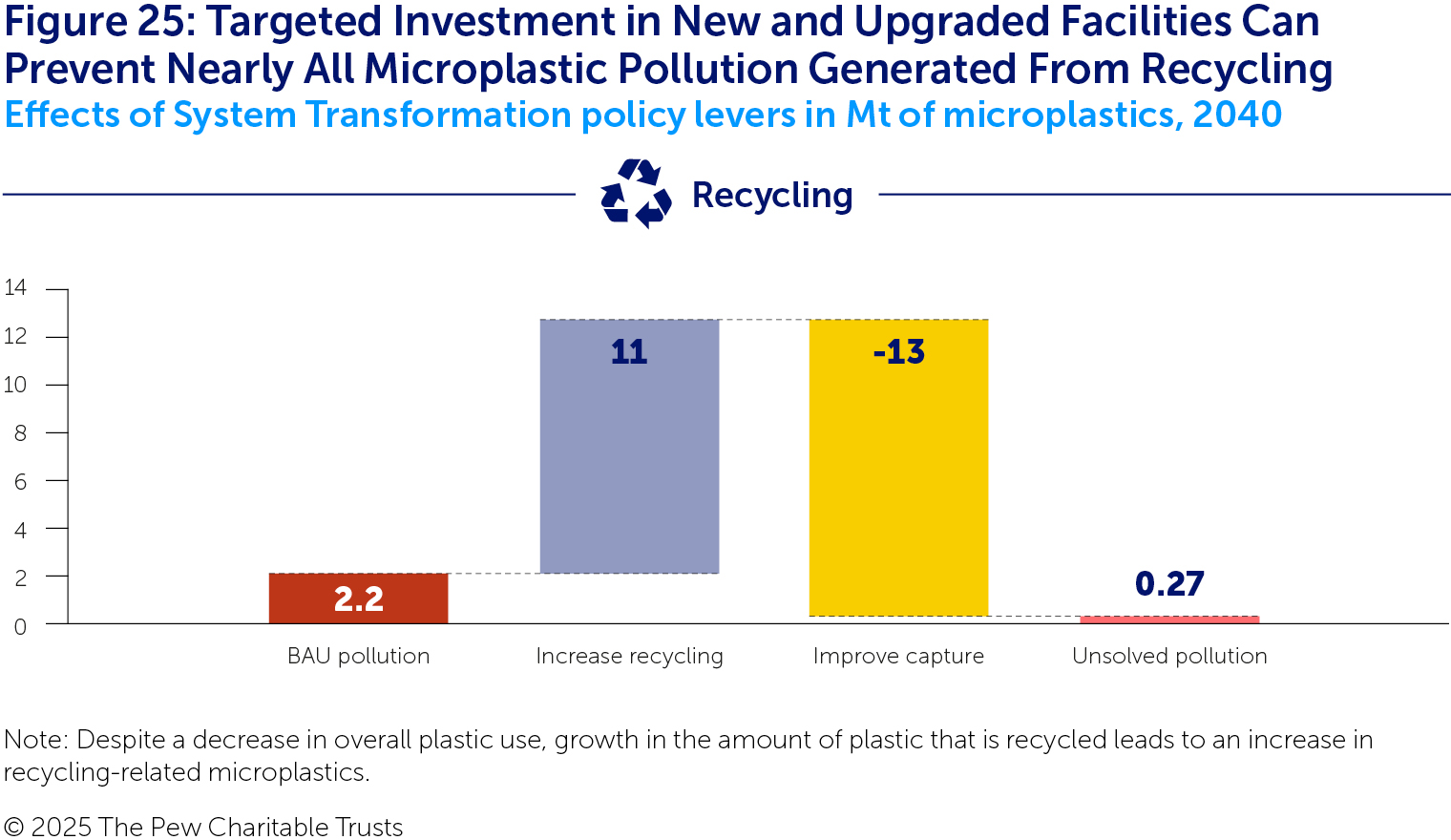

System Transformation achieves the largest absolute reductions in microplastic pollution by 2040 relative to BAU from tyres (-5.6 Mt), with smaller declines from the other six sources. However, the greatest percentage reductions are from pellet releases (-96%), recycling (-88%), textiles (-85%) and personal care products (-91%). Pollution from these sources could be almost eliminated if governments require the relevant industries to act.

Overall, however, System Transformation cuts cumulative microplastic pollution from 2025 to 2040 from the seven sources modelled by just 20% from 340 Mt under BAU to 270 Mt. More substantial reductions will require policies beyond those analysed in this report, such as ongoing updates to product design requirements across sectors. Paint is a particularly challenging source of microplastic pollution; the interventions modelled in System Transformation only reduce pollution from paint by 1.2 Mt, or 13%, making this sector a priority for additional research and innovation.

Although this analysis models more microplastic sources than BPW1, many sources that may substantially contribute to pollution are still unaccounted for, including artificial turf; fishing gear; packaging; detergents; automobile brake systems; geosynthetic materials used in civil engineering; oil and gas production and drilling processes; industrial abrasives (to remove paint from surfaces); and mismanaged macroplastic waste.99 We estimate annual macroplastic pollution at 260 Mt by 2040 under BAU, and as that material degrades, it will inevitably contribute to microplastic pollution.100

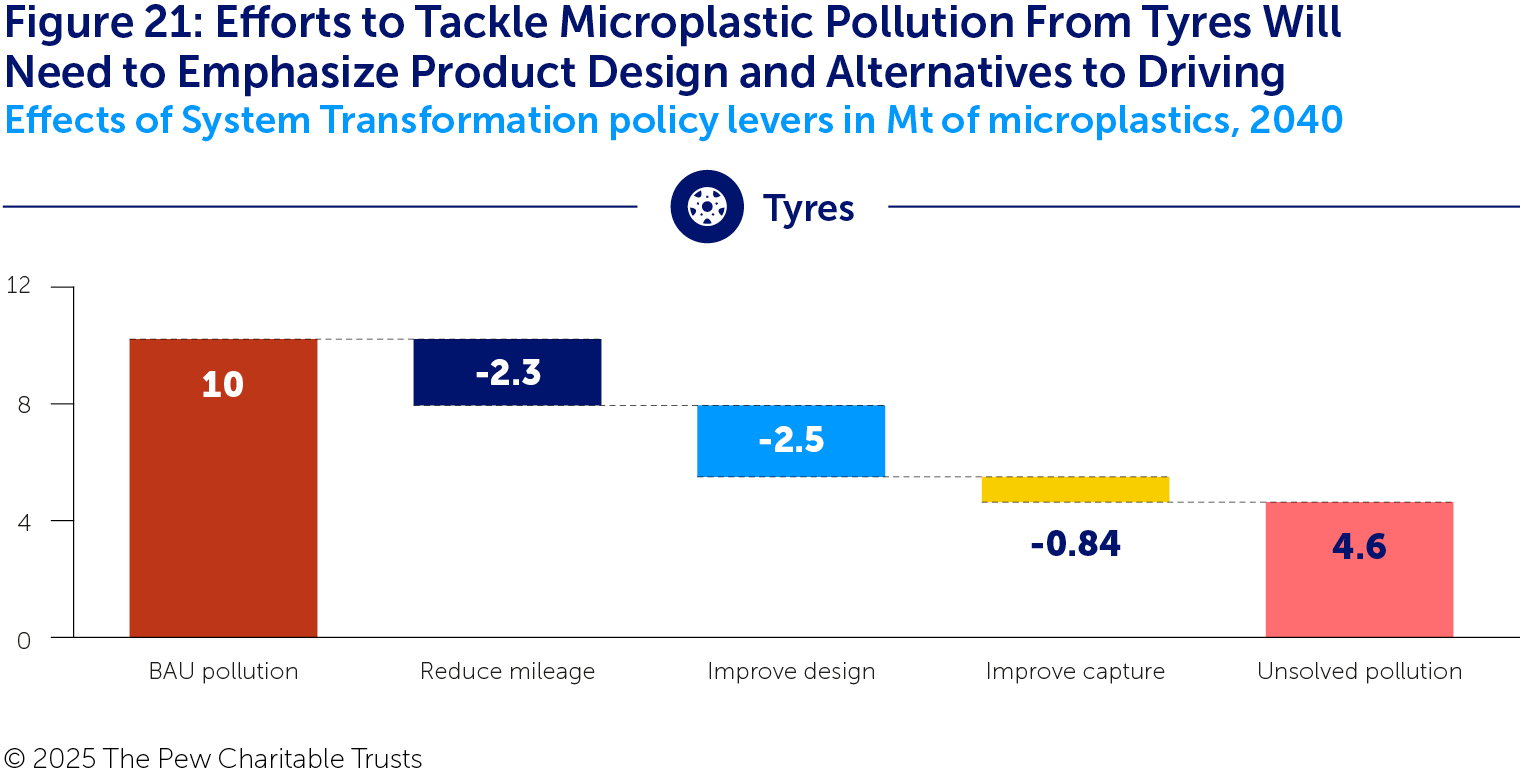

By 2040, System Transformation reduces microplastic pollution from tyres by 5.6 Mt, or 55%, relative to BAU

Using three policy levers – enhancing product design to reduce shedding rates, reducing overall tyre usage via broader transformations in the transportation system and installing drainage systems on roads to capture tyre particles – System Transformation reduces microplastic pollution from tyres by 55% by 2040 relative to BAU. (See Figure 21.)

Of these levers, improving product design – for instance, to lower abrasion rates – is the most effective in cutting microplastic pollution from tyres, delivering 44% of the reductions in this sector. Tyre abrasion rates vary widely across products on the market. For example, for one type of tyre, rates range from 35 milligrams (mg) to 126 mg of abrasion per kilometre travelled per vehicle ton.101 Importantly, the low end of that range demonstrates that manufacturers already can produce tyres that meet safety and performance standards and have wear rates well below what other products offer. Establishing abrasion limits that increase in stringency over time will remove the most polluting tyres from the market.102

Yet, even with the reductions from these levers, tyre wear remains a substantial source of microplastic pollution in 2040 and further action – such as making abrasion limits stricter over time – will be needed to progressively reduce pollution.

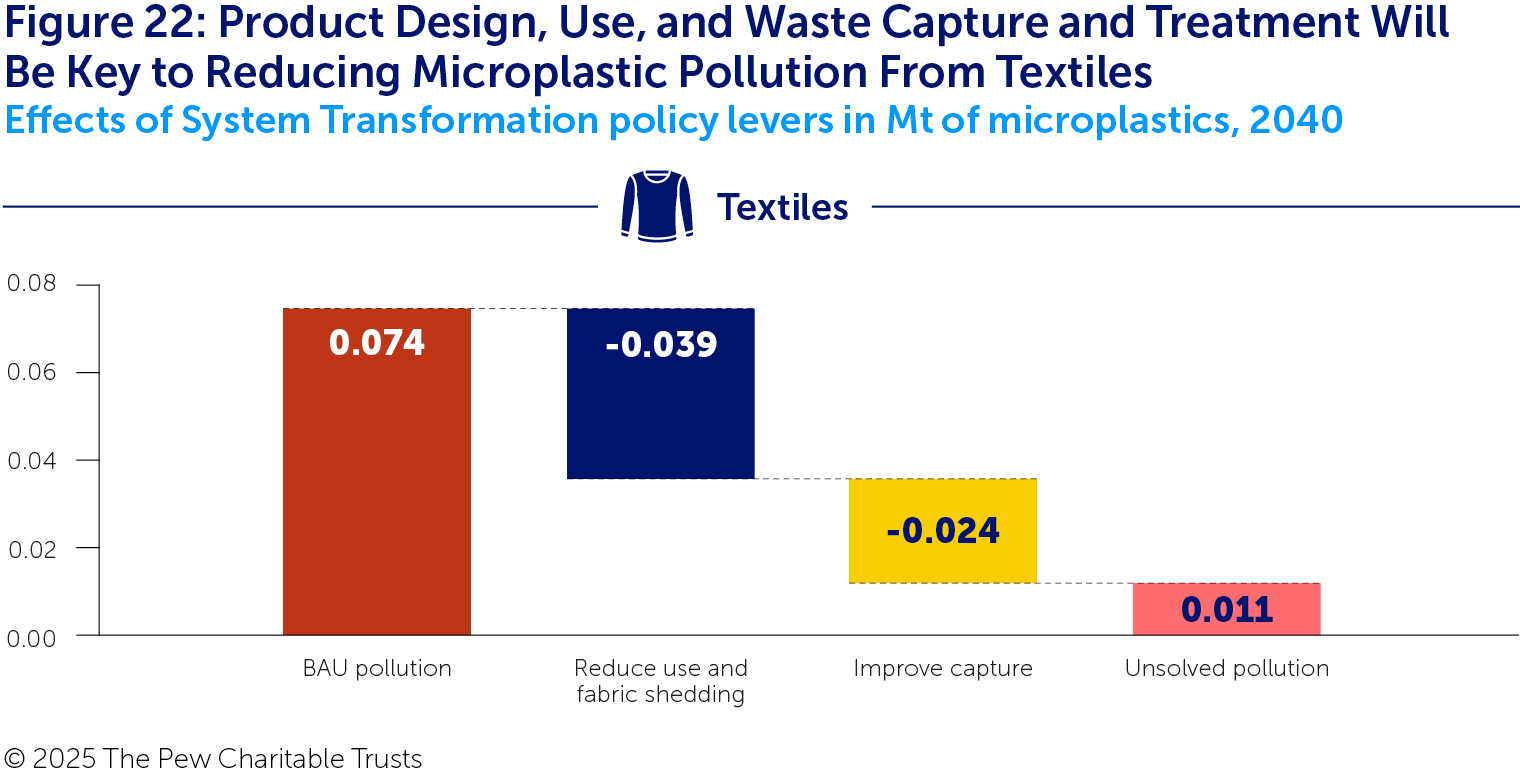

System Transformation cuts microplastic pollution from textiles by 85% relative to BAU by 2040

System Transformation targets microplastic pollution from textiles through multiple policy levers that reduce microplastic generation at the source and improve the capture in households and wastewater treatment plants of what remains. The levers targeting microplastic generation employ best practices in fibre and fabric manufacturing to produce textiles with lower shed rates and filter production wastewater, both of which can substantially reduce the creation and loss of microplastic over a garment’s life cycle.

Improving product design is the most effective policy lever in this sector, accounting for 52% of the cuts in microplastic pollution from textiles. (See Figure 22.) Product design requirements could include maximum shedding thresholds and use of cutting and weaving processes that reduce microfibre generation and could help encourage innovation in low-shedding textiles.103

Reducing demand for new fabric – such as by increasing the durability of clothing and discouraging fast fashion – or substitution with natural fibres can also help decrease microplastic pollution from textiles.

Further, although we do not model the use of recycled content in textiles, studies have shown that textiles made with recycled PET release more microfibres during wear and laundering than those made with primary PET, highlighting the need for a nuanced assessment of textile recycling practices in relation to microplastic pollution.104

And all policies introduced to reduce microplastic pollution also must ensure that new solutions do not introduce new harms, such as using toxic coatings, dyes or additives.