Millions of Homeowners Who Rent Land Are at Risk of Price Increases or Eviction

Survey shows that more than half of manufactured home owners on rented land have no lease, so terms could change

Manufactured housing represents a critical opportunity to create and preserve lower-cost housing options in the United States, but many of these homeowners do not own their land—and millions don’t have leases that could prevent unexpected rent increases or eviction, according to a survey by The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Today, manufactured housing provides unsubsidized housing to about 17 million people nationwide. About half own both their home and the land like other single-family homeowners, but unlike other types of housing, more than a quarter (an estimated 5 million people) own their home but rent their land. This is especially common in metropolitan areas. And Pew’s 2022 survey of manufactured home residents shows that only about half of those who rent their land actually have a land lease. Those who don’t may find themselves in precarious situations as rents or rights to stay on the land could change with little notice or ability to move the structure.

All renters, not just manufactured home owners, rely on leases to clearly define their costs, outline the terms of their tenancy, and provide certainty about the length of time that they can remain in their homes. Leases for manufactured homes are especially important because these structures—though transported from a factory to the land—are difficult and expensive to move after installation. As a result, homeowners could confront significant consequences if they cannot afford the land rent, if the land is sold, or if they are evicted. For example, they could have to sell or move—or face loss of their home—if they fall behind on payments.

That does not need to be the case. There are multiple approaches to land leases that could be used as models for policymakers to improve homeowner stability and that would reduce the risk of unexpected changes in land rents or displacement and expand renter protections. For example, some states require renewable leases, restrict eviction to only when the landowner has a legitimate reason or “good cause,” and set minimums for notice of changes.

Many resident-owned communities—manufactured home communities owned by the homeowners—provide perpetual (standardized long-term) leases. In addition, minimum lease terms and protections are required for an owner of any manufactured home community (MHC) to qualify for a loan through Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, the government sponsored enterprises focused on housing. And some research has suggested that lease provisions could be longer, with defined rent increases for better tenant stability and access to financing.

Manufactured homes on rented land are often older and purchased with cash

Because information about manufactured home residents is scarce, Pew commissioned Ipsos to field a nationally representative survey of 1,252 manufactured home residents. The survey included questions about whether respondents had a land lease and, if so, what the term length was. It found that 53% of manufactured home residents own both their home and land, 29% owned their home and rent the land, and 18% rent both the home and the land. Owning the home and renting the land is uncommon outside of manufactured housing and differs in several important ways from owning both the home and the land.

First, owned manufactured homes on rented land are more likely to be older: 19% live in homes built before 1976, when the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s standardized manufactured housing code was enacted, compared with 7% of those who own both home and land. Second, owned homes on rented land are less likely to be purchased new, compared with those who own both home and land (20% versus 40%, respectively). Third, most buyers who rent their land report purchasing in cash (71% versus 42% who own both home and land).

Many who rent land do not have a lease

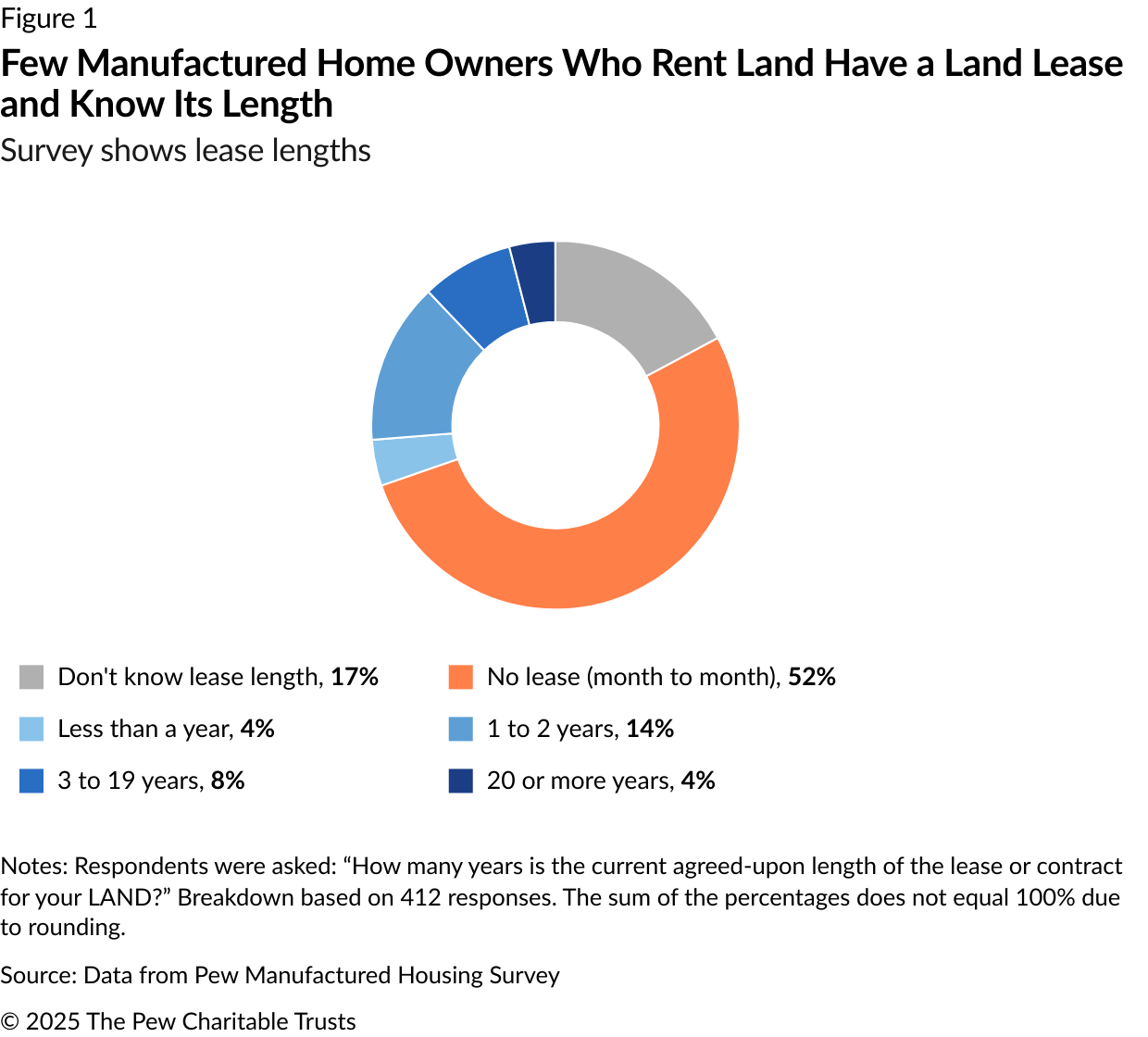

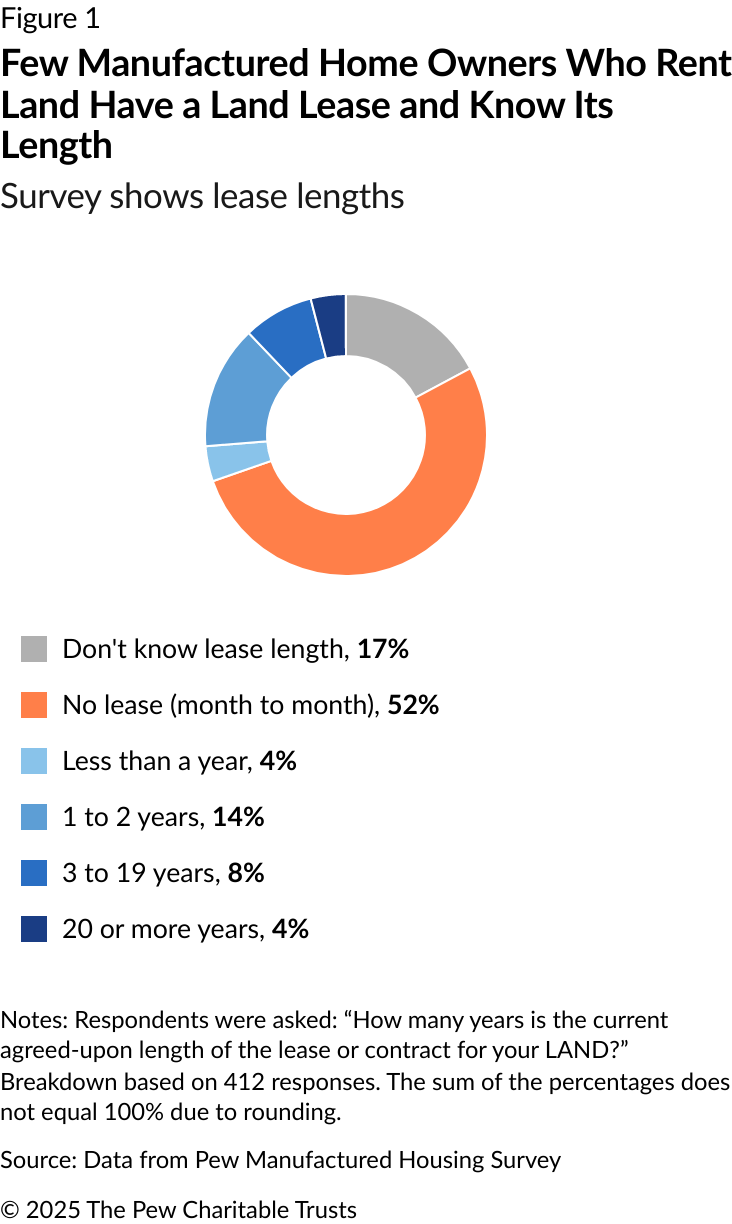

Of Pew survey respondents, just over half—52%—of manufactured home owners who rent their land said that they don’t have a lease for the land beneath their home, essentially living month-to-month. This amounts to nearly 3 million people. Another 17% don’t know the length of their lease.

Among the 31% who have a lease and know the length, 4% said it was less than a year, 14% had a lease of one to two years, 8% had a three-to-20-year lease, and 4% said 20 or more years. (See Figure 1.) In comparison, 32% of all U.S. renters report that their lease is month-to-month, 60% have a one-year lease, and 9% report another lease length, most of which are between one and two years. The vast majority (85%) of manufactured home owners who lease land live in an MHC rather than on individually owned land.

Ramifications of having no land lease

The lack of land leases for manufactured homes is troubling and far more common than in the site-built home market. It means that residents could be evicted from their land or face large rent increases without much warning. For manufactured home owners who lease their land, needing to move is especially problematic because transporting a manufactured home once installed is rare and costly. Forbes estimates the cost at between $5,000 and $15,000, which could amount to five to seven years of equity for some homeowners. Finding a new location to install the home can be challenging as well. As a result, an unexpected increase in rent or eviction from the land can result in loss of the owned home and equity altogether.

In addition, manufactured homes tend to be located in areas of greater natural hazard risk than site-built homes, making some residents more vulnerable to disasters, but more modern homes may be less vulnerable. Research from the Urban Institute shows that new manufactured homes built to current code are as climate-resilient as site-built homes.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency uses a lease’s length to confirm home occupancy when renters apply for federal disaster aid. Not having a lease also makes getting a security deposit back after a disaster more challenging. Leases list out renter and landlord responsibilities in the event of disaster, including rental abatement clauses—the ability to make partial payments if part of the unit is damaged—and lease termination clauses. Not having a lease makes disaster recovery more difficult for those who lease the land.

Models for land leases

Several models for land leases could improve homeowner stability. Both Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac now require that any loan made to finance a community include at least a one-year renewable lease for every resident. Before putting these requirements in place, research by Freddie Mac showed that just 13 of 50 states had this requirement, with only eight of those also requiring a renewable lease.

According to Freddie Mac, one common practice among community owners, especially those who do not intend to own the property in the long run, is to offer a one-year lease initially and then month-to-month thereafter. This could help explain why lack of a lease is so common. State policymakers looking to improve the stability of residents in manufactured home communities, which tend to provide an important source of unsubsidized lower-cost homes, could consider adopting at least the one-year renewable land lease requirements unless there is just cause for nonrenewal. Freddie Mac’s analysis notes that community owners who intend to own the property in the longer term do not find one-year renewable leases challenging.

Many resident-owned communities use standardized long-term leases in all member communities. Right now, just 4% of homeowners—on land owned by for-profit businesses as well as nonprofits—have leases of more than 20 years. Both Fannie Mae and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) have recognized the benefit of having a long-term lease and are working to expand access to mortgage credit when the land lease is longer than the term of the loan.

For Fannie Mae, this is specific to resident-owned communities that meet the government-sponsored enterprise’s criteria. For the USDA, mortgages are now possible for new energy-efficient manufactured homes on leased lands owned by nonprofits or on Tribal land.

Rachel Siegel is a senior officer, Dennis Su is an associate, and Seva Rodnyansky is a manager with The Pew Charitable Trusts’ housing policy initiative.