States Adapt Transportation Funding Strategies to Meet Resource Challenges

50-state analysis highlights varied approaches to financing critical maintenance and improvements

The traditional revenue sources that state and local governments have relied on to maintain their highways, roads, and bridges are facing mounting pressures, forcing policymakers to reconsider the funding strategies used to pay for essential work.

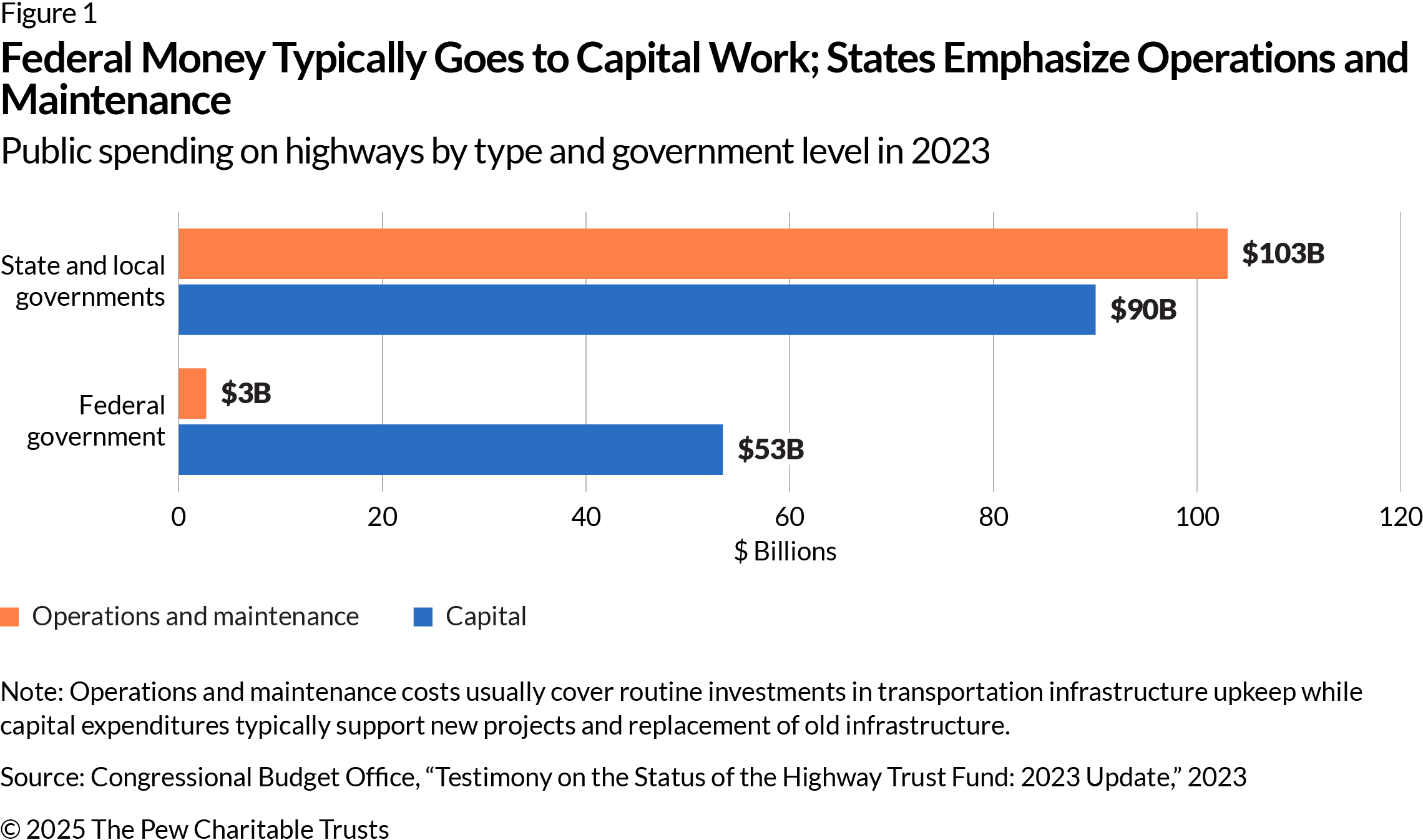

State and local governments spent roughly $203 billion on maintaining and improving their roadways in 2023—more than three times the total from the federal government, according to the latest data available from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). (See Figure 1.) The balance of funding sources varies, but states typically rely on a mix of federal aid, taxes on motor and diesel fuels, user fees, tolls, and bonds to pay for transportation infrastructure.

Policymakers are finding, however, that they cannot rely on some of these sources as much as they once did. Collections of fuel taxes in particular—a key source of state and federal transportation funding—are increasingly at risk because of improved fuel efficiency and the rise of electric vehicles (EVs) and hybrids. In addition, the federal gas tax, which has been 18.4 cents per gallon since 1993, has failed to keep pace with rising costs and spending needs. That has led to chronic shortfalls in the portion of the Highway Trust Fund that provides funding to states for maintenance and has required repeated transfers from the U.S. Treasury Department’s General Fund to sustain spending. Since 2008, multiple General Fund transfers have been made to the Highway Trust Fund, including a $118 billion infusion under the Infrastructure Improvement and Jobs Act (IIJA) in 2021. Meanwhile, states and localities face their own revenue declines, exacerbated by rising construction costs, higher borrowing rates, and uncertainty over future federal funding.

A growing gap in transportation resources

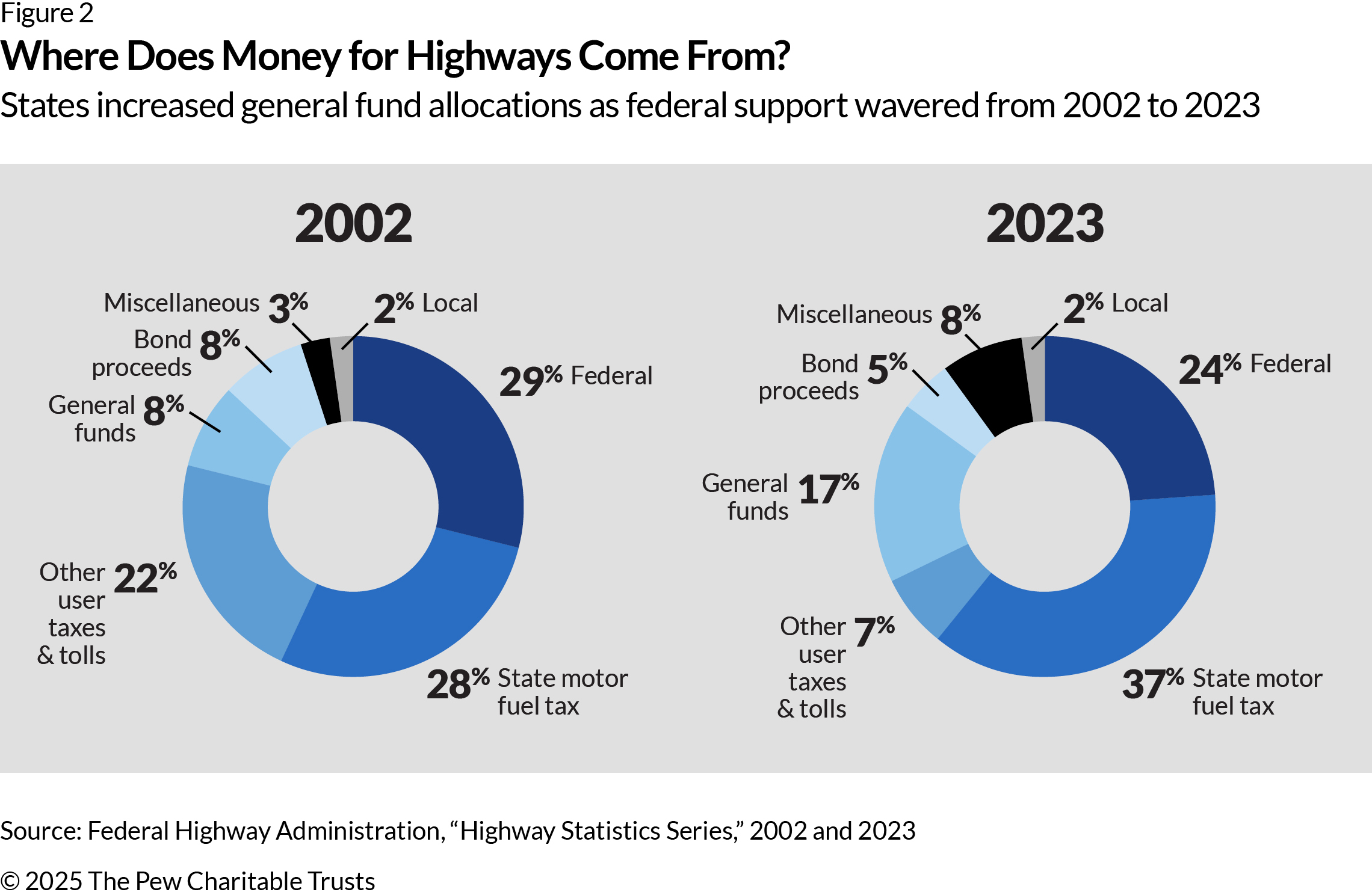

Over the past two decades, states took on a larger share of transportation funding, with state general fund contributions doubling from 8% of all transportation revenues in 2002 to 17% in 2023. (See Figure 2.) Meanwhile, federal contributions declined from 29% to 24% over that same time frame, even when taking into account the 34% boost in surface transportation programs compared with prior funding levels provided in the IIJA.

At the state level, the fact that motor fuel tax revenue grew to account for 37% of all transportation revenue can be misleading. Although gasoline tax collections have increased, this trend largely reflects steadily rising tax rates, not increased gasoline consumption. In fact, between 2002 and 2023, state gasoline tax rates increased by an average of 55% across states, with nine states more than doubling their rates within two decades. These hikes have helped to offset declining fuel use overall, but they may be an unsustainable strategy in the long term as consumption continues to fall.

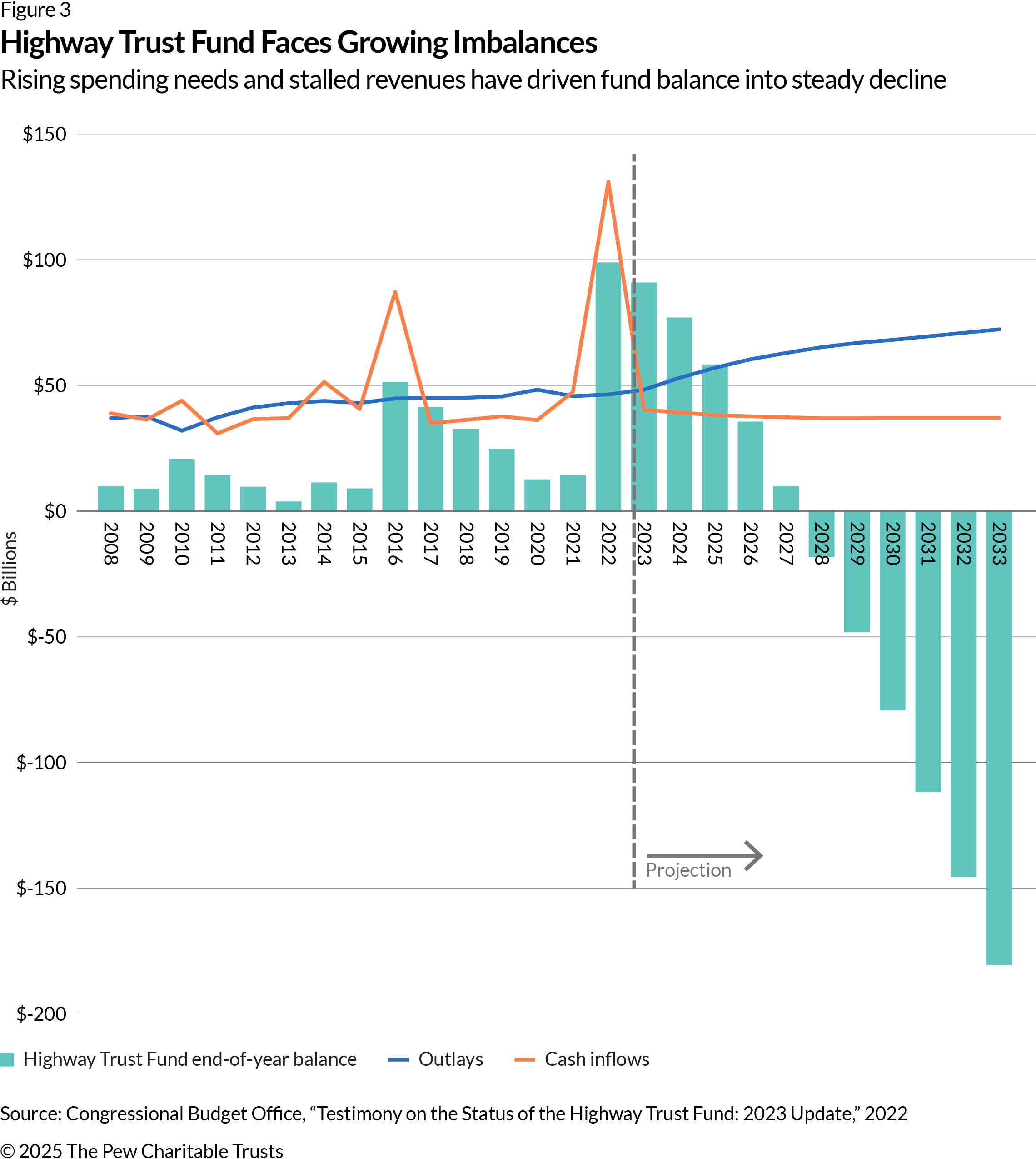

At the federal level, fuel tax rates—which the CBO says accounted for roughly 83% of the $48 billion revenues credited to the Highway Trust Fund in 2022—have failed to keep pace with infrastructure spending needs for nearly two decades. (See Figure 3.) In fact, the CBO has projected that, without additional funding, the Highway Trust Fund could be depleted by 2028. As of 2025, the office estimates that, given current spending and tax rates, the fund will need an additional $150 billion between 2027 and 2031 to cover its deficits.

In an April hearing, lawmakers from both parties raised concerns about the need to address Highway Trust Fund shortfalls before the 2026 reauthorization of surface transportation funding, while they acknowledged challenges to raising federal fuel tax rates or identifying new revenue sources. Some lawmakers said they are exploring a federal fee on electric vehicles, similar to the ones that some states have started implementing, to fill that revenue gap.

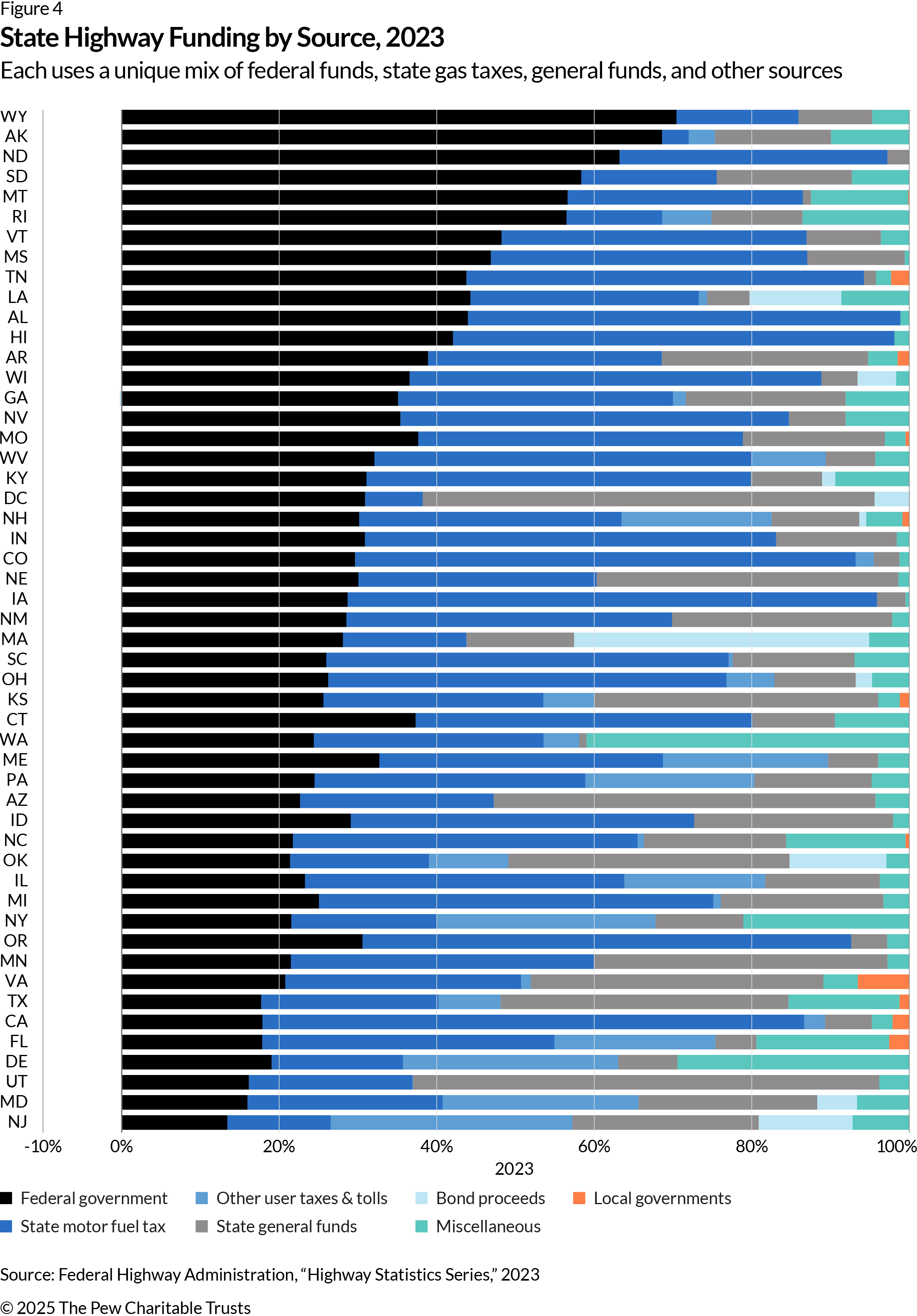

But that affects states differently because reliance on federal funds varies widely. For example, in 2023, federal dollars covered 70% of highway funding in Wyoming, but just 16% in Utah, where over half of the state’s transportation budget comes from its General fund. (See Figure 4.) While future federal funding levels are uncertain, states will need to closely monitor their reliance on these funds while adapting to ongoing uncertainty around the future of fuel tax revenue.

Rising costs and stagnant revenues

As states face revenue uncertainties, transportation construction costs continue to rise. The FHWA’s National Highway Construction Cost Index (NHCCI) shows a 63% increase in construction costs from January 2020 to July 2024, far outpacing other inflationary measures and making it more expensive to build and maintain roads and bridges. Some of these cost increases, initially driven by global supply chain disruptions during the pandemic, are expected to continue as tariffs make key construction materials, such as steel and aluminum, more expensive for states to purchase.

To supplement traditional road user fees and respond to rising costs, some states are shifting more general fund dollars and other revenue sources toward transportation. Michigan, for example, recently directed $600 million in income tax revenues, along with around $116 million from its marijuana excise tax collections to its Transportation Fund in fiscal year 2024, totaling $716 million. While gasoline consumption in the state has declined over time, changes to fuel tax rates in 2017 and 2022 helped maintain and even grow gas tax revenues. Today, Michigan’s Transportation Fund is supported not only by user fees, but also by reoccurring infusions from income tax and marijuana excise tax revenues, which now account for roughly 18% of the fund. Still, Michigan faces a $3.9 billion annual transportation funding shortfall and policymakers are considering additional revenues and taxes to close this gap.

Meanwhile, some states are already seeing sharp declines in gas tax revenues. Since 2019, Pennsylvania has lost about $250 million annually in these revenues as drivers use 430 million fewer gallons of gas each year.

How other states are preparing for funding uncertainty

The uncertain picture forming around future funding has left states increasingly concerned about the long-term sustainability of their transportation budgets. In April 2025, in response to declining revenues, Washington approved a $15 billion transportation budget with a plan to gradually increase fuel excise taxes and implement higher registration fees.

California, meanwhile, is expecting a 30% drop in fuel tax revenues over the long term as the state accelerates EV adoption to meet its climate goals. Connecticut also projects gas tax collections to decline through 2026 and has begun allocating a portion of general sales tax revenue to its Special Transportation Fund to compensate for that change. New Mexico, which currently has one of the nation’s lowest gas tax rates at 17 cents per gallon, also anticipates significant transportation revenue losses by 2030.

As the use of electric and hybrid vehicles grows, several states are exploring alternatives to fuel taxes through programs such as road user charges (RUCs), which charge drivers based on miles traveled rather than fuel consumed. Oregon, Utah, and California, for example, have launched pilot programs to assess feasibility, though concerns surrounding privacy and administrative costs remain. However, RUCs may not be a one-size-fits-all solution. While the charges do link road use to revenue, many states already rely heavily on user-based funding, including tolls, fees, and fuel taxes. In 2021, these sources made up over 50% of highway funding in 32 states, according to a recent analysis by the Tax Foundation. RUCs could supplement these revenues but are unlikely to fully replace them.

Additionally, at least 39 states have added new EV registration fees to offset gas tax declines, Montana and Kentucky also tax the electricity used for charging by the kilowatt hour, similar to gas taxes. Virginia has taken a different approach, by raising vehicle registration fees and implementing congestion pricing on express lanes to make up for lost fuel tax revenue.

Balancing short- and long-term planning and solutions

While states are addressing funding gaps by reallocating general funds, shifting tax revenues, and adjusting fees, relying on a single measure or approach will provide only temporary relief. The long-term sustainability of such steps is uncertain as budgets face competing demands and rising infrastructure costs. Without proactive planning, states risk ongoing shortfalls that could undermine transportation investments. A more stable approach may lie in blending and braiding multiple funding streams, leveraging diverse, coordinated sources to reduce the volatility of relying on limited sources.

State policymakers are looking at potentially sustainable solutions. Some are piloting RUC programs, increasing EV registration fees, or taxing electricity used for charging, though these efforts face political and administrative hurdles. Strengthening long-term capital planning, integrating revenue modeling, and incorporating transportation funding into broader budget assessments will be essential for managing costs, addressing deferred maintenance, and ensuring infrastructure resilience. With uncertainty over federal funding beyond 2026, states will need better tools to forecast gaps and adapt to an increasingly complex financial landscape.

Ora Halpern and Elijah Gullett are associates and Fatima Yousofi is a senior officer with The Pew Charitable Trusts’ state fiscal policy project.