Alabama's Cross-Agency Data System Strengthens Opioid Crisis Response

State agencies harness each other’s data to have a clearer understanding and to better coordinate responses

Overview

Like millions of Americans, many Alabamians have been affected by opioid use disorder. From 2006 to 2014, fatal drug overdoses (including, but not limited to, opioids) in Alabama grew 82%. By 2016, the state led the nation in per capita opioid prescriptions, with a rate of 121 prescriptions for every 100 people.1

To address this growing concern, in 2017 Governor Kay Ivey ordered the creation of the Alabama Opioid Overdose and Addiction Council. Led by the commissioner of the Alabama Department of Mental Health (ADMH), the state health officer overseeing Alabama’s Department of Public Health (ADPH), and the state attorney general, the council (through its subcommittees) identified several distinct objectives, including fostering more data sharing among health care providers, policymakers, and other key stakeholders. Early on, the Data Committee, which Governor Ivey’s 2017 executive order established and that included 25 members from mental health, public health, Medicaid, corrections, and other state agencies. recommended creating a central data repository (known as DrugUse-CDR, or simply CDR) to overcome the legal and confidentiality barriers impeding data collaboration between different public agencies and private organizations. Originally funded through what is now the Department of Justice’s Comprehensive Opioid, Stimulant, and Substance Use Program, the CDR today is financially supported by ADPH and implemented by the University of Alabama’s Institute of Data and Analytics.2

Under the university’s technical management since 2018, the CDR initially pooled data from sources such as the state’s departments of public health and mental health and the Alabama Law Enforcement Agency, later adding other data sources from poison control, insurers, and other organizations. By analyzing this cross-sector data, public health officials, researchers, policymakers, and others can see and understand opioid and other substance use problems holistically, use the data to develop strategic approaches to curb overdoses, and measure the effectiveness of ongoing initiatives and improve them as needed. For example, early data analyses showed that opioid use is often associated with other drug use, which led the CDR to expand and incorporate data on various types of drugs.3

The CDR’s work also plays a role in better informing the public and key stakeholders on opioid and other substance use in Alabama through easy-to-understand dashboards, which provide interactive data views with breakdowns by county, gender, and other categories.

This brief features information drawn from interviews that The Pew Charitable Trusts conducted from November 2024 to January 2025 with six Alabama officials who have designed, implemented, and/or participated in the state’s CDR, including public health leadership, representatives from multiple state agencies, and a technical implementer from the University of Alabama.

These conversations revealed numerous promising components for a successful data sharing practice, such as:

- Ensure utility of the data being shared.

- Minimize burden on data providers.

- Always demonstrate value.

- Identify a wide range of potential partners.

This issue brief is part of a collection of publications that examine promising data sharing practices involving public health. It is a resource for state and local health officials who are seeking new ways to make better use of available data to improve their communities’ health. These insights can help officials in other jurisdictions build and strengthen their data sharing infrastructure to foster more collaboration between health departments, health care providers, social services agencies, and other public and private institutions. These data-driven collaborations will support more effective, evidence-based solutions for public health concerns.

The Benefits of Alabama’s CDR

The Data Committee assembled and quickly identified the need to develop the CDR as part of the state’s multifaceted approach to tackling the opioid epidemic. The creation of the CDR addresses the state’s need to have “rapid access to current data,” with the repository ultimately playing an important support role in coordinating responses to the opioid crisis throughout the state.4

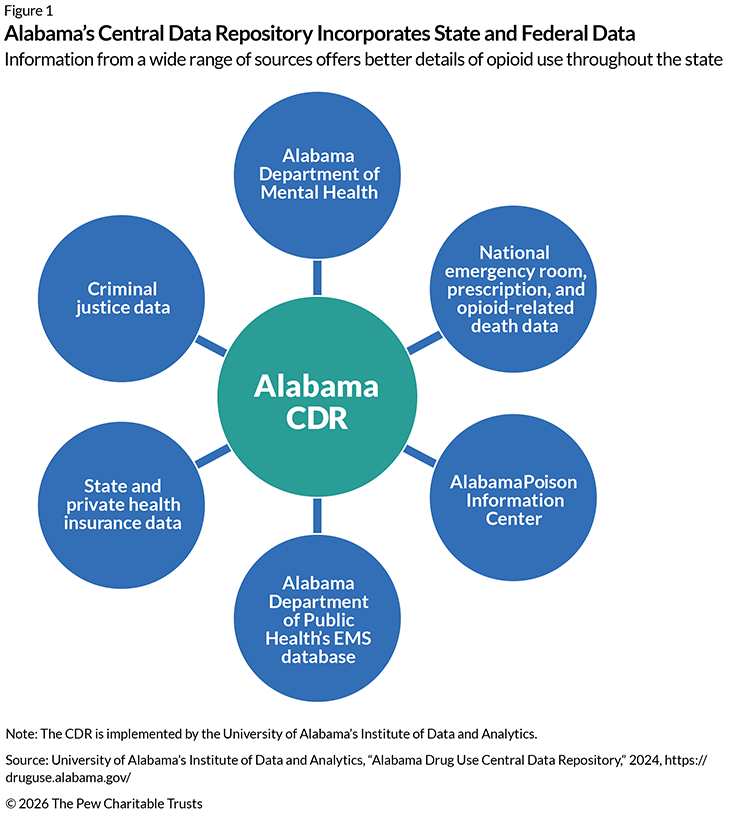

As several interviewees noted, the very act of building the CDR and its continued work have been integral in opening communications among historically isolated state agencies and increasing data transparency with the public. By compiling and cooperatively analyzing data from a wide range of sources (see Figure 1), Alabama created a resource that not only serves the needs of the council and state agencies by providing a more robust look at opioid use and related issues across the state but also provides valuable information about the crisis to the general public via data dashboards.

By establishing accessibility to this cross-sector data, Alabama has benefited in multiple ways. For example, when data analyses showed state officials that overdoses per capita were much higher in one county than others, ADMH responded by focusing prevention and peer-support programs in that county. Officials also used data from the CDR to apply for and obtain grants, including federal funds, that support many of the state’s opioid-related programs. County-level officials disseminated data and findings from the CDR when presenting to community groups and giving lectures, helping to raise greater public awareness around the risk of drugs in the community and offering a platform about overdose prevention and response. More broadly, state agencies are using the CDR as an evaluation tool to identify areas where they are performing well and where they need to improve, and what populations are underserved and require interventions most urgently.

Lessons Learned

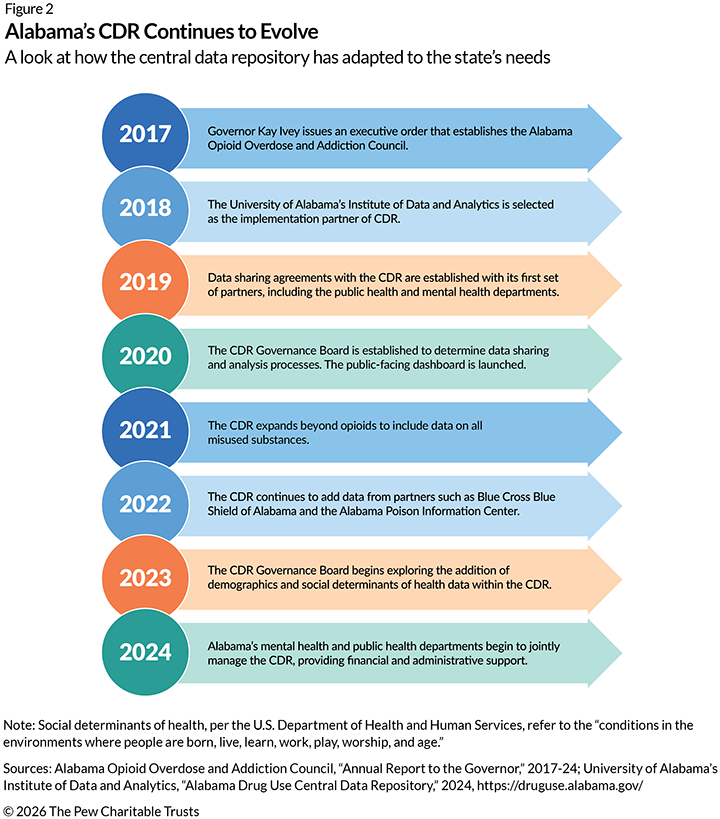

Alabama’s experience designing and implementing the CDR over the past eight years (see Figure 2) can guide other states as they look for opportunities to enhance collaboration across state agencies and with external partners to improve public health outcomes.

Focus on feasible first steps and crafting an adaptable model

Although fully developing a comprehensive data sharing practice takes time and effort, public health professionals can use early data to begin answering questions and informing decision-making even in the initial stages of building the practice. That is, programmatic staff and policymakers do not need to wait for a fully developed system before they can reap the benefits.

In the early stages of Alabama’s work, ADMH and the Data Committee overseeing the CDR’s work drove efforts to get state agencies to share their data with the CDR even without a mandate requiring participation. While identifying datasets and building relationships across different agencies, ADMH staff found that it was important to prioritize datasets that are easier to share (for example, because they rely on established relationships between those on the council and agency leaders or they have lower legal barriers that do not necessitate as much involvement by agency lawyers).

Gary Parker, chief data officer at the Alabama Medicaid Agency, said that it is important to identify a use case that can be the starting point for a data sharing practice. Although it means that the practice may not be as robust early on because of limited data sources, it will help build momentum for growth by focusing first on collecting and analyzing initial datasets that can generate actionable information quickly and provide the business case for future expansion of the practice.

Early efforts should also reflect the needs of potential partner agencies within the state. Parker described how it is important to consider value propositions when engaging with potential data providers and to be ready to answer questions such as:

- “What is the benefit that we [the state agency] are going to gain?”

- “How is participation in the data repository going to benefit the state?”

- “How is the data repository going to improve what the state agency is doing?”

Adapting the data sharing practice to answer those questions can generate greater buy-in and collaboration.

Be clear about the purpose of the data sharing practice

Alabama officials said it would be challenging to bring data together without having a clear, concrete use in mind. They advised determining clear and meaningful uses for the data up front before sharing it into the repository.

The CDR serves several purposes for Alabama’s participating agencies. First, it improves the participating state agencies’ understanding of how effective programs throughout the state are in terms of affecting substance-related outcomes (such as health services utilization for overdoses, opioid prescriptions, and opioid treatment; overdose-related EMS incidents; and Core Opioid Treatment Metrics such as diagnosis, initiation of and retention in treatment, and recovery) and allows for a comprehensive evaluation of cross-agency data.

Second, state agencies also use CDR data in support of federal grant applications. Funded grants using CDR data have played a role not only in maintaining the CDR itself but also for intervention activities within the state, such as drug diversion court programs. Researchers and state personnel can more easily apply for grants and conduct other data analyses, as having multiple streams of data housed under one umbrella means that they no longer must hunt down data from various state agencies. And third, the CDR data allows agencies to create visualizations that inform a wide range of audiences—including the general public, agency leadership, and state legislators—about the ongoing opioid crisis within Alabama.

- Have realistic expectations about the data included in the CDR and how it can support users and policymakers. Several types of data made sense to include in the CDR as they directly related to health issues of interest. However, the limited frequency of how often the data is updated (e.g., death certificate data) and legal restrictions in sharing specific types of data (e.g., prescription drug monitoring program data) did not easily allow the CDR to build momentum for its use in the early years of implementation.

- Ensure that all stakeholders clearly understand objectives throughout the process. The lengthy startup and the number of stakeholders involved complicated early use of the CDR, which made it difficult to keep everyone working in parallel efforts. Along with clear objectives, officials also recommend ensuring that there is sustainable funding for the data sharing practice, an important component in its ultimate success.

Build trust and generate buy-in

Building the CDR required more than just data pipelines—it required deep trust among agencies. Several Alabama officials said it was important for those leading the CDR efforts to build trust with participating state agencies, which had not previously taken part in similar statewide data sharing efforts. They noted three pathways for building trust in the CDR.

First, the council engaged the University of Alabama to manage the data through a request for proposal process. State agencies were much more willing to share their data with an independent trusted third party, rather than an agency with which other agencies competed for influence and funding.

Second, the council also gave participating state agencies a seat on the CDR’s Governance Committee, providing a voice to data contributors and allowing them to take part in decision-making processes and the selection of additional data sources to pursue. Matthew Hudnall, an associate professor at the University of Alabama, noted that this model was “an important factor that other states should consider adopting as well.”

And third, state agencies contributing data also maintain ownership of their data, ultimately approving or vetoing every use of their own data. Hudnall said that agencies are going to be “very reluctant” to simply hand over data to a third party and hope the data is used appropriately. While this review of all data requests results in more work for the agencies, providing this ability enables their trust and has led to greater participation in the CDR. Hudnall also emphasized the importance of framing that the data still belongs to agencies, who retain full control over it, with the CDR simply acting as a “partner in holding [the] data.”

Beyond the CDR itself, engagement and collaboration have increased across agencies as a byproduct of this trust building. For example, Parker noted that participating in the CDR created opportunities for the Alabama Medicaid Agency to help peers in other state agencies analyze data beyond the opioid-related data found in the CDR, including that related to public health, mental health, corrections, senior services, and youth services.

Through multiple conversations meant to help state agencies understand the purpose behind cross-agency data sharing, the Data Committee could generate buy-in for the CDR. Clearly explaining the CDR’s goals and value up front created a viable pathway for success.

“None of this works without executive buy-in,” Parker said. Similarly, Hudnall said, “If it weren’t for [state agency leadership], we would not have been able to move past many of the hurdles (such as legal or technology concerns)” that exist when executing a data sharing practice like the CDR.

While some of the buy-in was a byproduct of long-established relationships between those on the council and other agency leaders, it was also necessary to establish new lines of communication with other state agencies. Data Committee heads held early conversations while building the CDR to elevate the potential of the data sharing practice not only with agency leadership but also with programmatic staff who could identify the data their own agencies held and communicate their data needs from other state offices to both committee members and their respective agency leaders. State officials noted that these conversations provided transparency and reaffirmed commitment to the data sharing taking place, while also ensuring that everyone is on the same page. That commitment and the shared understanding of the work were both critical to the CDR’s success and will continue to be as further data sources are added.

Ensure fairness in data sharing processes

Alabama officials described the critical need to keep all data contributors on a level playing field. On the legal front, all agencies contributing data signed the same memorandum of understanding that ensured that every agency was operating under the same general terms. To accommodate different laws governing various types of sensitive data, individualized data sharing agreements were then crafted for each contributing agency.

The Data Committee and the University of Alabama also provide a uniform data sharing mechanism for all participating agencies, making it simpler to contribute to the CDR. Agencies are invited to share data in whatever format works best for them, thereby easing the burden by not imposing a predetermined format that might require more up-front work by some agencies than others. While this requires the University of Alabama to standardize the data once received, the Data Committee saw meeting agencies where they are (both from a technical and relationship standpoint) as the correct approach to take.

Promising Practices For All States

- Ensure utility of the data being shared. Have a realistic understanding of what bringing data together from multiple agencies may help the state to accomplish. Couple that with a strategic plan to guide data sharing efforts. Make sure that shared data is updated regularly.

- Minimize burden on data providers. When engaging with potential partners, be clear about the purpose of data sharing and ensure that partners know that they are not being asked to collect new data. If new data streams are necessary, keep them to a minimum to lessen the burden on agencies and encourage participation. Be flexible in the data formats that are accepted into the shared repository.

- Always demonstrate value. Even after the database is authorized and operating, it is critical to continually show stakeholders—executive leadership, especially—that the investments of time and resources are yielding tangible benefits.

- Identify a wide range of potential partners. Be open to partners beyond what is typical within the state. Successful collaboration may be found with groups outside of government agencies, such as universities or other independent trusted third-party organizations. Once engaged, treat all partners in a fair and transparent manner.

Conclusion

Alabama’s experience demonstrates the importance of bringing together state agencies that do not frequently communicate to address large-scale health issues. Its CDR is helping state officials better identify program needs to address the opioid crisis and has opened pathways to improved interagency communications. Those leading the CDR use an approach centered on establishing trust, generating buy-in, and ensuring fairness to execute the data sharing work. Other states can learn lessons from Alabama as they work to build their own public health data sharing practices.

Acknowledgments

This brief was researched and written by Pew staff members Ian Leavitt, Josh Wenderoff, and Margaret Arnesen. Thanks also to Pew staff members Kimberly Burge, John Murphree, Tricia Olszewski, Abi Ingoglia, Sara Miller, Heather Cable, Ruth Lindberg, and Kathy Talkington for their contributions. The project team thanks the state officials who participated in the interviews informing this brief as well as its external collaborators, including the Population Health Innovation Lab at the Public Health Institute (Seun Aluko, Beverly Bruno, Stephanie Bultema, Katie Christian, Sue Grinnell, April Aihan Phan, Kendra Piper, Esmeralda Salas, and Rebecca Williams), which conducted and analyzed all interviews, and Amy Killelea, who helped with conceptualization of the guiding research questions. The team is also grateful to its external reviewers for their support in reviewing this piece prior to publication, including Katie Greene and Joe Gibson. Although they have reviewed the report, neither they nor their organizations necessarily endorse this brief’s findings or conclusions.

Endnotes

- Alabama Opioid Overdose and Addiction Council, “State of Alabama Opioid Action Plan” (2017), https://mh.alabama.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/AlabamaOpioidOverdose_AddictionCouncilReport.pdf.

- Matthew Hudnall et al., “Lessons Learned From Developing a Statewide Research Data Repository to Combat the Opioid Epidemic in Alabama,” JAMIA Open 5, no. 3 (2022): ooac065, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35919378.

- Matthew Hudnall et al., “Lessons Learned.”

- Alabama Opioid Overdose and Addiction Council, “State of Alabama Opioid Action Plan.”