Alaskan Native Lands Could Lose Critical Protections

Tribal leaders oppose congressional reversal of management plans

In the Yukon and Kuskokwim River watersheds, which together cover a huge portion of interior and western Alaska and where salmon returns have been declining for over a decade, Tribes have worked for years to have their voices heard in the management of federal lands and waters. In 2019, 20 Tribes formed the Bering Sea Interior Tribal Commission to protect their way of life and conserve the lands and waters upon which they depend. The commission has since grown to 40 Tribes and has engaged in multiple federal planning efforts to ensure that these Tribes have a meaningful role in decision-making.

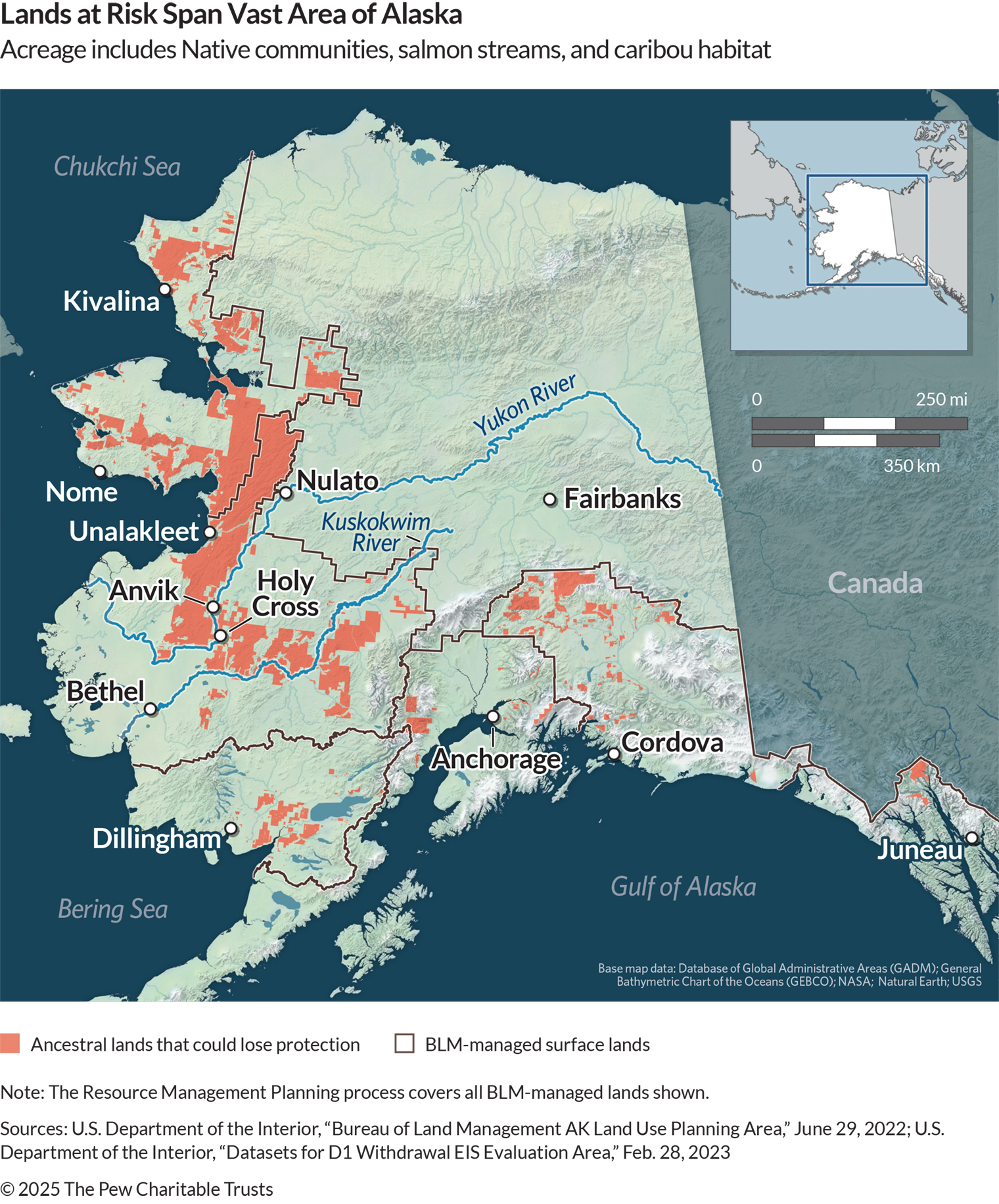

These efforts include defending the Central Yukon Resource Management Plan (RMP) and protections of so-called D-1 lands—named for a section of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act that assigned management of those lands to the U.S. Secretary of the Interior. Together, these two impacted areas cover nearly 40 million acres of federal land.

Unfortunately, these protections and management approaches that Tribes and Indigenous communities in Alaska have worked so hard for over the years are facing threats from far away.

On Oct. 9, 2025, a bill passed in both houses of the U.S. Congress that would revoke the Central Yukon RMP, creating uncertainty and potentially reverting management to a decades old framework that does not reflect the will of the sovereign Tribes who live on the land. This reversal occurred even after Tribal leaders from the commission urged federal legislators to retain the current balanced management plan. It now remains unclear as to how the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) will proceed with the Central Yukon plan.

“On the heels of the seventh summer without our usual salmon harvest, we are stunned at the idea [that] our leaders would impose more uncertainty around the management of the Central Yukon lands that surround us,” said Mickey Stickman, former first chief of the Nulato Tribe. “The threat of losing our federal subsistence rights, and confusion over how the caribou, moose, and salmon habitat will be managed, is overwhelming. Despite deep involvement and over a dozen years of going to meetings and government-to-government consultations, our voices are being silenced and the future of our food security thrown up in the air.”

D-1 lands were originally protected under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971. Since that time, tens of millions of acres have been transferred from the BLM to state and private ownership. Although more than 50 million acres of D-1 lands remain protected, the agency is evaluating whether to remove protections for more than 28 million of those acres. These lands are hunting, fishing, and gathering grounds for more than 100 Indigenous Alaska communities and include areas that border national parks, wildlife refuges, and the Bering Sea. In fact, more than 130 federally recognized Alaska Tribes, including those in the Bering Sea Interior Tribal Commission, have called for retaining the protections, noting the importance of the D-1 lands for salmon spawning and rearing, caribou wintering, and moose habitat critical for food security. Also importantly, because these lands are federally managed, the BLM’s own rules prioritize the subsistence use of fish and wildlife by rural Alaskans over other uses.

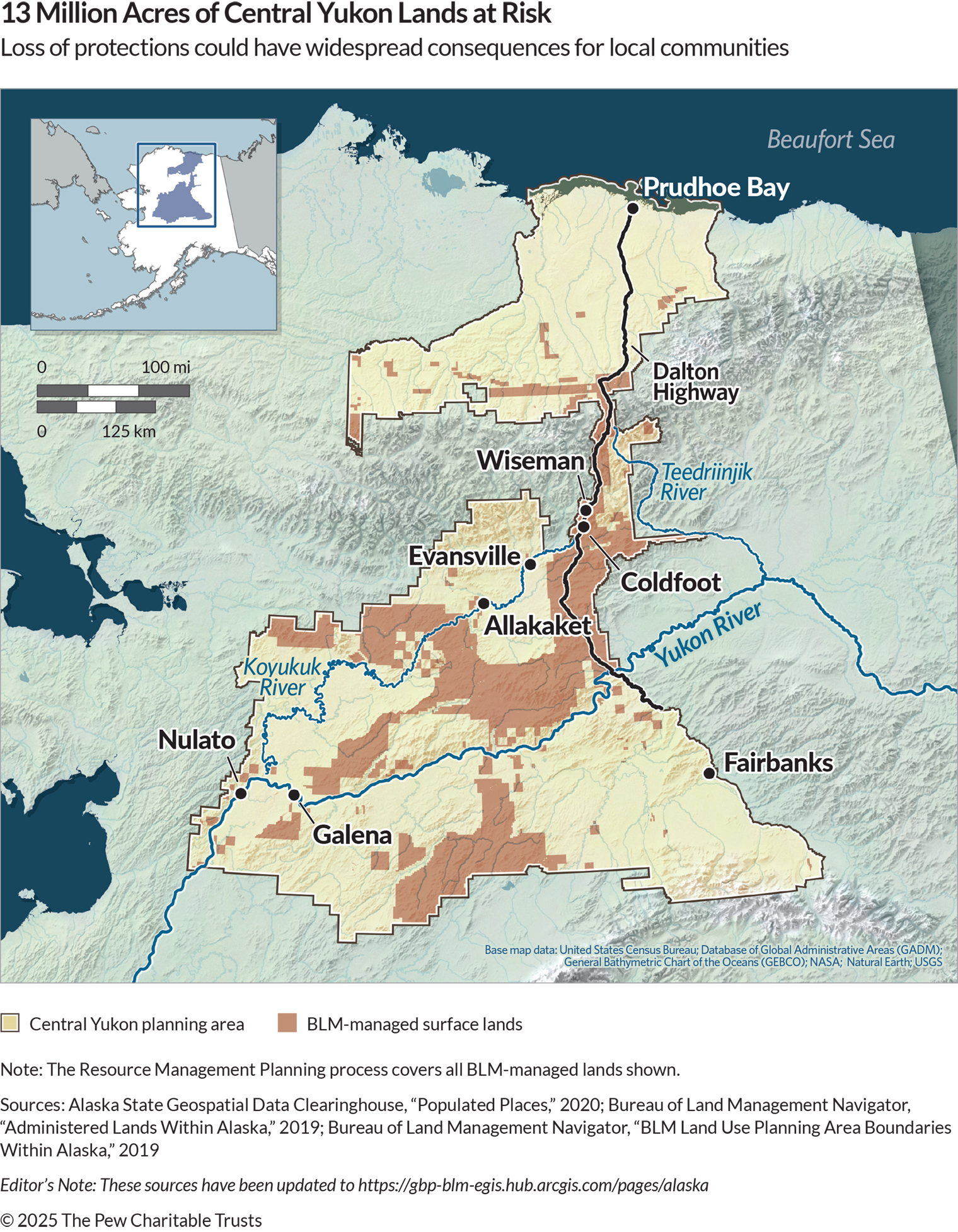

The BLM adopted the Central Yukon RMP in November 2024 after more than 10 years of public engagement, scientific analysis, and consultation with Tribes in Alaska. This plan improved protections for more than 13 million acres in interior Alaska and established a management approach that balanced conservation with other uses.

The plan was developed in collaboration with Tribes and stakeholders to provide special management for salmon, caribou, and Dall sheep habitats, including protections for 3.6 million acres of salmon-producing watersheds and restrictions on mining, oil and gas development, and other potentially damaging activities in important habitats and cultural areas.

Removing these protections will have dire consequences for the traditional ways of life practiced by Tribal members and Indigenous communities throughout the region. Pew encourages federal leaders to use the existing plan amendment process to make any needed changes to the Central Yukon RMP and consult with Tribes regarding D-1 lands before making any changes to the current management framework.

Native peoples in Alaska have lived in harmony with the natural environment for millennia, stewarding the land, maintaining their traditional ways of life, and ensuring food security for their communities. The Indigenous knowledge and experience Native peoples have developed over centuries is an invaluable resource, not only for their own communities but for federal policymakers charged with managing Alaska’s pristine ecosystems.

It is essential that management reflects this knowledge and experience of Tribes. Pew will continue to collaborate with and support our Tribal partners to safeguard the lands and waters they call home.

Steve Marx supports Alaska Indigenous peoples’ fishery management and marine conservation priorities for The Pew Charitable Trusts’ U.S. conservation project.