As the U.S. Nears Its 250th Birthday, Dissatisfaction With Democracy Is Widespread

The nation stands out among international surveys of democracy for critical views of leaders and institutions

Since its founding, the United States has often been referred to as a “grand experiment” in democracy, but as the nation approaches its 250th birthday, many Americans think the experiment is going badly: In a spring 2025 Pew Research Center poll, 62% were dissatisfied with the way democracy is working.

This sense of democratic frustration is hardly unique to the U.S. Research organizations such as the Economist Intelligence Unit, Freedom House, International IDEA, and V-Dem consistently say that the world is in an era of democratic decline—or sometimes, democratic backsliding, erosion, or recession—as polarization grows and crucial democratic norms weaken.

The Center’s international surveys find that people around the globe still largely believe in democratic values, but they are critical of their leaders and institutions. Most see elected officials as out of touch, and many say there is no political party that truly represents their views. And all of these frustrations are exacerbated by economic anxieties and deep cultural fissures driven by rapid social upheaval.

But even in this moment of shaken global confidence in democracy, the U.S. stands out in some unfortunately negative ways. For example, in a 2023 survey of 24 nations, 83% of Americans said elected officials do not care what people like them think, making the U.S. one of only five countries where 80% or more held this view.

The U.S. also belongs to a group of high-income nations where people want political reform but are pessimistic about the prospects for it. The Center surveyed 25 countries in 2025, and in seven of them, including the U.S., roughly half or more of the public said that the political system needs significant change and that they are not confident the system can change. These seven nations are all high-income countries where dissatisfaction with democracy tends to run high, and, on a variety of measures, faith in politicians often runs low.

The U.S. stands out in other ways as well, including views about the impact of technology on politics and society. In 2022 and 2023, we asked people in a mix of high- and middle-income nations whether social media has been more of a good thing or bad thing for democracy in their country. A majority of Americans (64%) said the latter, the most negative assessment among the 27 nations polled. Similarly, the Center’s 2025 survey showed that Americans are more concerned about the increased use of artificial intelligence in daily life than most other nations polled.

And worryingly, the U.S. is often an outlier in our surveys for its high levels of social disconnection and division. Although a majority of Americans (66%) in 2023 said they feel close to other people in the country, that was among the lowest percentages of the 24 nations polled. And Americans had the second-lowest percentage on a similar question about feeling close to people in their community.

Americans were more likely than any of the 17 high-income publics surveyed in 2021 to say that there are strong conflicts in their country between people with different racial or ethnic backgrounds.

And the U.S. is regularly at or near the top of the list when it comes to partisan and ideological divisions. Nearly 9 in 10 Americans (88%) in 2022 said there are strong conflicts in the country between people who support different political parties—second only to South Korea among the 19 countries polled.

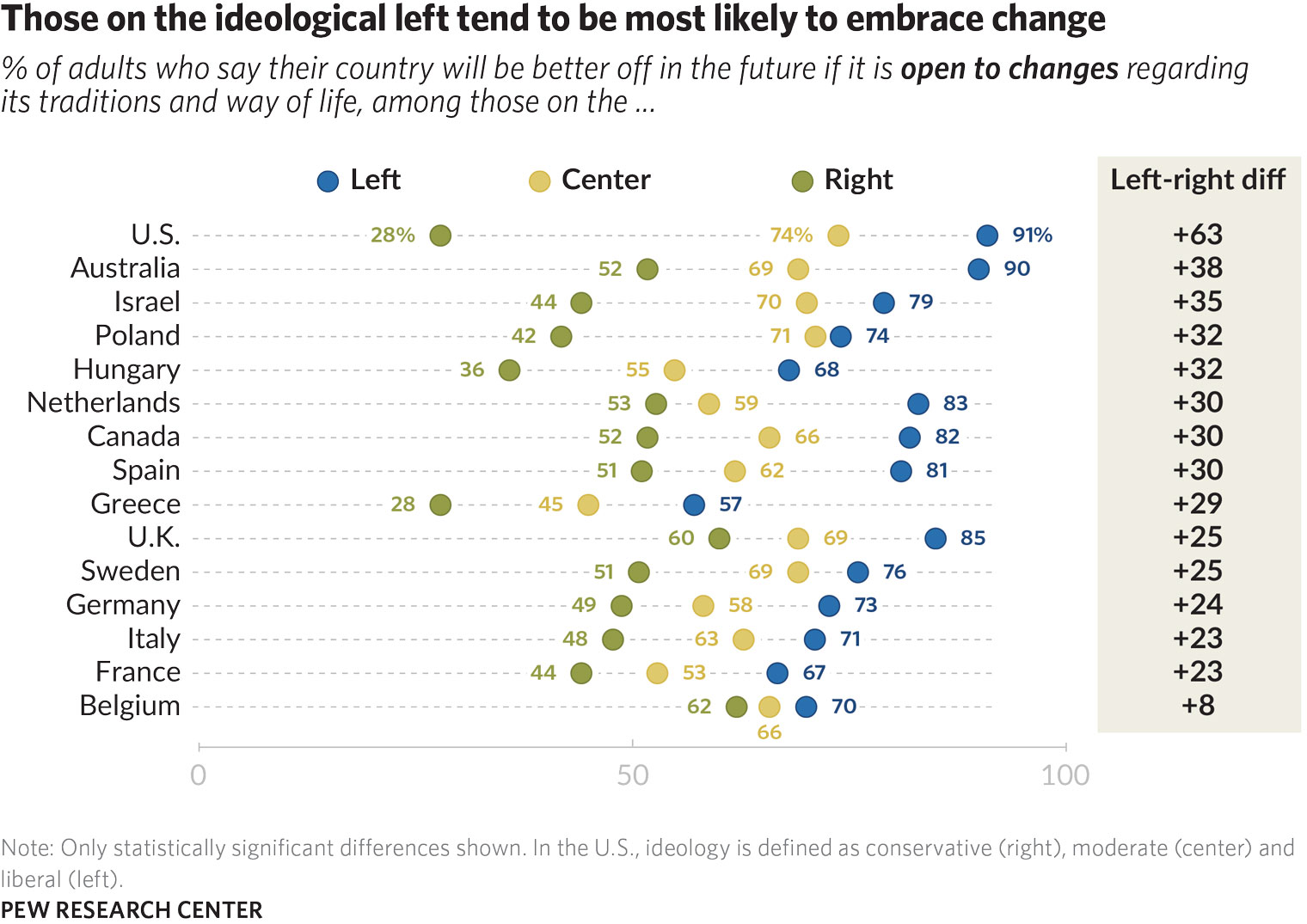

On issue after issue, the gap between right and left is especially wide in the U.S. This is true on social as well as economic issues. And the U.S. has exceptionally large ideological divisions on questions about international politics, including opinions about climate change, terrorism, and the United Nations.

Americans are particularly divided on a question that is designed to explore overarching orientations toward change and tradition. When asked in 2022 if the U.S. will be better off in the future if it sticks with its traditions and way of life or if it is open to changing them, 91% of liberals said we are better off if we embrace change, compared with just 28% of conservatives—by far the largest ideological gap among the 19 countries in the study.

As many scholars and writers have documented, divisions between Democrats and Republicans in the U.S. have intensified over time as the two parties have evolved from relatively heterogenous coalitions of different interests into relatively like-minded groups of partisans. Ideological, racial, religious, and other identities have coalesced in ways that can make it feel like the country is increasingly becoming opposing camps that see two very different Americas. And politics increasingly feels like a zero-sum competition between these camps.

So, after 250 years, is the experiment out of steam, or are new and better ways of doing democracy still possible?

Americans have some ideas for achieving the latter. In 2023, we asked people in the U.S. and 23 other nations to describe in their own words what would help improve the way democracy is working. Americans had a lot to say. Two sets of ideas topped the list.

First—and this was true in many other countries as well—people expressed a desire for new and better political leaders who are more responsive, competent, and honest, among other characteristics. We know from other questions we’ve asked that many people believe having leaders with different backgrounds and experiences would improve policies. For some, that means more women, young people, labor union members, and people from underprivileged backgrounds. Others want to elect more businesspeople and religious leaders.

Second, the U.S. was the only country surveyed where government reform was the most frequently mentioned idea (it was tied with getting new political leaders). Our polling has found broad support for specific reforms, such as term limits for Congress, age limits for federal elected officials and Supreme Court justices, and abolishment of the Electoral College. Many express a desire to curb the power of special interests and to reduce the role of money in politics.

But to achieve the reforms they want, Americans will have to regain confidence in their collective capacity for change. They will need to create a shared sense of purpose and new unifying forms of American identity that allow them to transcend divisions and trust one another long enough to pursue a healthier democracy. Over the past 250 years, the nation’s very imperfect representative democracy has often found the capacity to meet its challenges, becoming, at least at times, more democratic and representative. Today, many Americans would say it’s time to discover that capacity once more.

Richard Wike directs global attitudes research at Pew Research Center.